Carl Lee Griffith

Born October 10, 1915. Died June 1, 1999

Active Service 8/18/42

Rating and Rank: (see text below)

Carl Griffith entered the Army Air Corps on April 18, 1942. He attended service school in AC Harlington, Texas, where he trained for six weeks as an aerial gunner. He was also trained as a bombardier. He was later stationed at LAAF, Lakeland, Florida assigned to the Third Bomber 55th Wing, Group 344, Squadron 495 where he was trained in bombing maintenance.

In January, 1944 he was stationed in Europe in Stansted, England. During this time he flew approximately 32 missions. After, about his third mission, Griffith was reassigned from tail gunner to bombardier. This meant that he would receive a field commission to lieutenant. This commission has been disputed by the Air Force in spite of their own documentation (MACR) showing that Griffith was serving in the navigator/bombardier role. All bombardiers were lieutenants. According to Frank Carrozza, non-commissioned officers serving in this role were called toggeliers. Carl Griffith was not titled as such and so should have been recognized as a lieutenant.

On May 28, 1944 he was assigned as the bombardier of a B-26 marauder. This was not the Shopworn Angel, his usual plane. The Shopworn Angel was undergoing repairs after having been belly landed by Captain Clay who had borrowed the plane in a previous mission. Captain Woodrum was not happy that the plane that he and his crew (including Griffith) were used to flying was out of commission.

According to Captain Woodrum’s son, Hank Jr., the crew did not expect to fly that day do to the condition of their plane and spent the previous evening out on the town. To their surprise that morning they were assigned to fly on a mission using a different plane whose captain had fallen ill.

The mission was to bomb a railroad bridge in Paris, France. At roughly 11:45 a.m. in the vicinity of the target the planes encountered anti-aircraft fire. Griffith’s plane was hit on the left wing and a fire ensued. Griffith released the bomb load as was the protocol. The plane went into a dive.

According to the MACR, co-pilot Irwin Morgan bailed out through the nose wheel hatch, engineer-gunner Richard Burton exited via the waist window, and Griffith through the bomb bay. Griffith was wounded by flak on the way down.

“After I bailed out and before reaching the ground, I noticed two German soldiers tracking me on a motorcycle with a side car. As I landed in a wooded section the Germans did not see me. They were on a side road and had a machine gun pointed in my direction. I was armed with a 45 pistol and thought if I could shoot them I would have a chance to escape. I did make that attempt and when I missed they saw where I was and started firing at me with a machine gun. By this time I knew I didn’t have a chance so I threw out my gun and stepped out from behind the tree. They came running up and I think they were telling me to put up my hands. As I knew no German, I just stood there. This is when they started hitting me with a pistol. I was knocked down numerous times and all the blows were around the head. My nose was broken and several teeth knocked out after the beating. I could not hear out of my left ear for several months. I have been bothered with dizziness ever since.”

It seems that Griffith had on his leather jacket indicating he was a bombardier. Our bombs had killed one of the soldier’s entire family. That was the one who doled out most of the beating and would have killed Griffith if the other hadn’t stopped him.

Griffith was transported to Paris in the motorcycle. The Germans paraded him through the streets. The French people were cheering him and giving him the “V” sign for victory. This infuriated his captors. Every time they saw this happen they would strike him in the head again as well as around the flak wound in his leg.

Griffith was taken to Frankfort on the Main for interrogation. He spent three nights in a cell that was too short to stand up in. It was like a cage and he was given no food or water. After three days he went in front of a German officer who told him the purpose of the cell was to break his spirit. Griffith said they did a good job of that. Next, he was sent to a camp in the Baltics (perhaps Steline). Griffith can’t remember how long he was there. He was then shipped by boxcar to Nuremberg. There were fifty men in the car. They were packed in so tightly they couldn’t stand up or hardly move. They were in the car for nine days with no food or water. There was no place to urinate or go except on yourself. Griffith said the smell was unbearable. About thirty percent of the men died.

From Nuremberg, he was marched to Mossburg (Marspo). Griffith said it was one hell of a trip. They slept on the ground at night. The flak wound on Griffith’s leg became infected and swelled to the size of a watermelon. Griffith described how he was helped on the march by a bunch of refugees that allowed him to hold on to the wagon so he could drag his leg. If he had stopped the Germans would have shot him like they did to many of the soldiers. Along the way, Griffith saw a trench that was full of bodies. He could smell the trench from a mile away. As he passed it he saw the Germans putting something on the bodies…perhaps lime. When he arrived at Mossburg he was very sick with strep throat. Fortunately, Patton’s forces liberated the prisoners. The doctor at the field hospital said that his throat was closing and that he could have died by the next day. Griffith was flown back to an army hospital in Chicago. His weight was down to 62 lbs.

Griffith spent three months in the Chicago hospital. Here he learned that his young wife had left him and taken their small baby with her. He was desperate to find her and leave the hospital that reminded him of his experiences as a P.O.W. In order to leave without medical clearance, Griffith was made to sign a document stating that he was medically fine, and that he was not a commissioned officer. He was, however, far from medically fine, and he was a commissioned officer. He signed the document so that he could expedite his release, and he lived to regret it. He left the hospital with the aid of a cane.

In a letter to the Veteran’s Administration in Griffith’s behalf, his daughter Susan Barbour stated, “He has been denied his rights from the very beginning. Many of his war records were destroyed in a 1974 St. Louis fire. The absence of the records to document his claims has been used against him. I have watched my father suffer from ulcers, loss of hearing and smell, vertigo, chronic pulmonary disease and other things, not to mention what a year in a P.O.W. camp did to his soul.” “I have spent many hours in V.A. hospital waiting rooms and have spoken to many vets. Many of them corroborated the fact that it was quite common for wounded soldiers in army hospitals to be coaxed to sign releases stating they were not medically injured so that their release could be expedited.” “I wonder how many ex-POW’s or injured soldiers put their lives on the line, and once they were no longer needed, being ushered out of the service with a loss of the rights promised to them.” “The greatest unfinished business of the Second World War is human pain and how it has not been dealt with.”

Griffith and his daughter continued their campaign. It was not until the 1990’s that Carl Griffith was presented the Purple Heart he deserved as well as enhanced disability status.

To this date Griffith has not been assigned his proper rank. He was honored in his local newspaper.

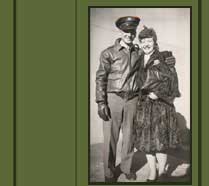

Carl Griffith’s daughter Susie was able to find three pictures of Griffith during the war.

Probably Griffith and the first crew of the Shopworn Angel. Griffith is in the front row on the left.

See the letter the War Department sent to Griffith’s wife when he was missing in action.