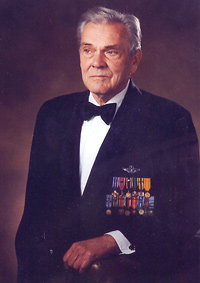

“This Is It” Colonel Robert Witty

Bob Witty

Commanding Officer, 11-7-44 to 8-17-45

344th Bombardment Group

|

|

|

Tryon Daily Bulletin, June 6, 1997 D-Day: The Memories Still Make Hearts Pound 53 Years Ago Today Editors note: Today is the 53rd anniversary of D-Day and Bob Witty, senior columnist for the Tryon Daily Bulletin, who commanded the 344th Bomb Group in WWII herewith presents a memoir of one of the missions that Group flew out of the United Kingdom in 1944. by Bob Witty

My teenage grandson has never evidenced the slightest interest in my military career, my war experiences, nor, in fact, anything about my past. So it was quite a surprise when he asked me to write him a letter about “the most exciting day you remember in WWII.” He explained that it was for his Grade 11 History class, an essay he was required to write. Oh. I didn’t have to rummage around much in my memory chest to answer the question. A 1944 strike that our B-26 Group flew out of Station 169, Stansted, in the U.K. was by far the most momentous. It was this that I chronicled for him, and brought back for me some long-repressed, vivid memories. Memory is at best fragile and ephemeral, seldom adequate to what actually happened, but I was determined to record it the way I remembered it. Our Group of four Squadrons had been hitting ammo dumps, marshaling yards and bridges all that Spring as part of the effort to soften up “Fortress Europe,” as Herr Hitler called it. I was awakened at 2:30 a.m. by the duty-orderly bringing me a steaming hot cup of welcome coffee, and the unwelcome greeting: “It’s pouring and blowing. Pretty lousy, sir.”

It always seemed to me that John relished these sadistic opportunities to roust me out with that kind of news, something to gloat over later in the mess.

I had been thoroughly briefed on this highly secret mission by the planners at 9th Air Force Head-quarters the week before, and now gathered together my charts and set them up in the Briefing Quonset to get ready for the 54 aircrews that would come straggling in, sleepily, during the next minutes.

From the moment the route was unveiled, and they saw the soon-to-be-famous target, the mood in the hut changed. It didn’t take my rather corny opening line, “This is it, gentlemen” to ignite the electricity of anticipation in that smoke-filled room. Remember, this was still in the days when while-coated doctors appeared in magazine ads heartily endorsing Lucky Strike Gold.

The short briefing over, 300 crewmen swept into the various mess halls, the high pitch of their chatter betraying the inner tension they felt. Bacon, fried potatoes and ersatz eggs were wolfed down as the crews whisked through chow in order to get out on the line to their aircraft, which by this tine were combat ready, with their eight, 500 pound bombs mounted in the bays.

To this day, 53 years removed, I remember the rumble and roar of 108 Pratt-and-Whitney engines as the ground crews ran them up, tested them and blessed them. The reverberations and staccato coughing shook the East Anglia countryside as the scene was replicated on 100 American Bomber and Fighter bases. The other indelible recollection I retain: a myriad of lights. Lights gleaming from the control tower through the misting rain, lights of the jeeps and weapons carriers darting over the tarmac, lights from the bombers as the crew chiefs performed their final checks. Using our lights was a luxury denied us on clear nights; tonight, with the fog and rain blanketing our base, there was no chance of enemy bombers finding us.

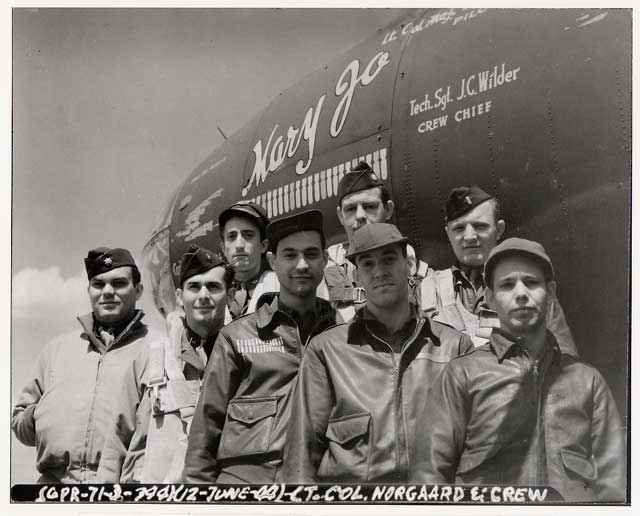

I was to fly this mission as Command Pilot in the copilot seat with the lead crew, a be-medaled outfit which had led the 344th Bomb Group again and again and was a typical polyglot American bomber crew under the command of Squadron Commander Jens Norgaard who had trained them since their fledgling days at MacDill Field in Tampa. The crew consisted of a Norwegian, two Jewish lads, two Irish, a Pole and a Hungarian.

Under Norgaard’s methodical preflight checking we reviewed emergency bailout procedures, inspected our French Franc issue in our escape-kits, our flak suits, our emergency rations, our pistols and maps; this careful attention to detail, the crew knew, might tilt the odds in their favor in case of a bailout or crash landing.

The banter of the mess was gone; in its place was a professional grimness, a stoic but confident attitude toward their mission. This was a crack crew, flying its 20th mission together and nothing would be left to chance.

With his wing lights stabbing twin holes in the misting night, Norgaard led the Group, like so many pachyderms, nose to tail, down the taxiways. Thin down the runway that night, with the fabled “metallic-taste” in their mouths, I’m sure my fellow crew members had their fingers (figuratively) crossed, as I did, in a nod to Lad Luck.

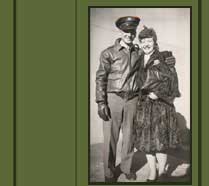

I mechanically helped Norgaard get the Mary Jo (named for his wife) into the air and having lived with the perils of this mission for a week in my mind I was echoing my last word at the briefing, “Godspeed.”

Joining up 54 twinengined bombers on a clear night was not easy; assembling them on course at 12,000 feet on a rain-swept night between clouds layers, was miraculous. Inside Mary Jo, the instrument lights cast a dancing, eerie-colored glow throughout the cockpit. Climbing through the clouds, the running lights of the other Marauders as they skillfully formed up on the leader, were reassuring. In 20 minutes we were formed and on course for one of the most memorable flights any of us would ever fly.

The three “boxes” of 18 planes had different targets on the Cherbourg Peninsula, but would stay together over the Channel and separate only for their bomb runs in to the individual aiming points. It was obvious as we roared South of London that we could not attack at 12,000 feet because of the clouds. We nosed the formation down to 10,000, then to 5,000 and then a bit lower. From there it was still possible for the bombardiers to use their Norden sights. Just barely.

As dawn spread slowly up out of the East, on the surface of the choppy English Channel we could make out the magnificent armada of 10,000 Allied ships bearing thousands of men to a rendezvous with history – a rendezvous that many would not survive. It was a riveting sight that none of us would ever forget: the largest assembly of ships and men and power the world had ever known.

The tension mounted as the gunners tested their twin 50-caliber machine guns preparatory to approaching Utah Beach; a crackling clatter so much a part of these methodically choreographed missions.

Our targets, three batteries of concrete imbedded coastal guns East of Cherbourg, on the Contentin Coast, were coming up fast now. The most vulnerable period of a bombing mission occurs when the aircraft has to be steadied on a level, straight-in course; flak and fighters make this brief, suspenseful period a veritable hell. But today the German fighters had been swept from the skies and the anti-aircraft fire was desultory, inaccurate.

The Group honed in on the massive gun emplacements and arrived at the three aiming points within 20 seconds of target time. One could sense the relief in the crew as the aircraft lurched abruptly with the launching of 2,000 pounds of bombs and the cry of Bombardier Parish, from his plexiglass perch in the nose, “Bombs away! Let’s get out of here!” Norgaard wheeled formation back out over the Channel, through a thin layer of clouds and spotty rain squalls. Mission accomplished.

I sensed a collective sigh of relief in our plane; there is a release of tension after a bomb run that crackles through the crew. The actual danger is not entirely over, but the most perilous moment is behind them.

Leveling off and heading for base, one of the aircraft in the third box received a direct hit from the sporadic ground fire and it was up on one wing, sliding fast toward the water trailing black smoke, a fiery doomed comet; no one witnessing a mortally wounded, blazing bomber on its final plunge will ever forget it. In my own case, it remains seared into my memory.

Later, when we arrived at base, BBC was to say that of the eight Marauder Groups involved that day, “Only two planes were missing of the 400 which struck the German fortifications.” Only.

Only 12 young men, lost in their prime. Only 12 families notified and destined to mourn forever. Only 12 sweethearts or wives left to ponder celebrating the “Return of the WWII Americans to East Anglia,” I hate it just as much as in the angst of that moment in 1944.

Norgaard touched the Mary Jo down gracefully and whilst flak jackets and helmets and woes were shed as he wheeled into the handstand, I knew what to expect: with the tension of the mission behind them, these very young men (only two on that crew were over 22) burst into talk; giddy, tension-relieved chatter that proclaimed, “We made it!”

The debriefing team had a time of it that memorable day, separating the enthusiasm of the moment from the hard facts and observations that were necessary for their report. And when the Flight Surgeons doled out their tot of post mission whiskey, the tales of derring-do became increasingly “interesting.” The upbeat, lighthearted dialogue that follows a combat mission is familiar to anyone who has participated. I thought of it as “Blather.”

Before the aircrews left the debriefing Quonset, reconnaissance P-38’s radioed that all three gun emplacements were destroyed; they, at east, would not operate against the Allied armada. With that flash report, a rousing cheer went up and predictably, everyone started talking at once. A not uncommon reaction to a relief of tension.

My hope is that David can use what I have recalled to help his class appreciate that isolated single mission in 1944, to fit it into their knowledge of WWII; to get the message of the 12 young men who were lost and to understand what one participant was thinking on that momentous day: D-Day, Operation Overlord, the Normandy Invasion … June 6, 1944.

Mr. Bob Witty is first on left.

ME-109’s MISTAKE: ATTACKS MARAUDER

A few days ago the first Me-109 to attack a crack Marauder finished at the bottom of the Channel. The Streak piloted by Capt. Clay was toiling home on one engine when the German pursuit far below zoomed up to cut down the isolated cripple. As he reared up with spitting guns astern, the American ship, Staff Sergeant George R. Anderson, a Californian, turned on his twin “choppers” in the tail turret and blew the attacker in half.

Besides the career of the Colonel, the Streaks take most pride in their association with Gen, Doolittle’s famous Tokio raid. Lt. Col. Bob Witty, 28, of Cleveland, Ohio, a former newspaperman and father of twin boys and second in command of the group, was among t o original volunteers for and planners of the Tokio mission, but to his eternal regret was one of the of the historic group in a Minneapolis Hotel who offered to go but he was turned down.

WITTY WINS HONOR TO LEAD STREAKS.

It became known on Monday that Col. Witty, who had been grounded for nearly two weeks for the special purpose, was to lead the Streaks over the Invasion Coast in the place of honor of the whole first invasion phase – the first American airplane group over the beachhead and spearhead of the invading American forces.

As soon as we arrived at the advanced air base from which we were to set out on D-Day the following Tuesday, all of us were warned not to discuss our assignment with the combat crews who had not then any inkling of what impended.

On Sunday, the Silver Streaks piled off from the airfield in the green wooded English countryside side for their last run before the invasion. They were set to pound the 300 foot high trestle railway bridge over the river Seine just above Rouen, France. A magnificent placement of bombs cut the bridge in three places and sent it tumbling into the river.

WAIT H-HOUR WITH JAVA AND SANDWICHES.

Next day, the eve of D-Day, all machines of the Silver Streak group were grounded, and all personnel on the field were confined to camp. Those of us who know that the invasion was to take place on the morrow and that the paratroops would be landed behind the German lines just before dawn packed our kits and sat by drinking black coffee and eating massive cheese sandwiches waiting for reveille, which was timed for half an hour after midnight.

There was no air of ill-suppressed excitement. None of us outside the Colonel and a few others knew at what spot the first American invasion was to land. We knew that we would know at 2:30 when we were briefed.

But we did not know that perhaps thousands of lives depended upon the accuracy of the “Silver Streaks” bombing; that the job was to stun into stupidity the horde of German troops crouching under concrete shelters facing the beach where American troops were to spearhead the Army of Deliverance into France.