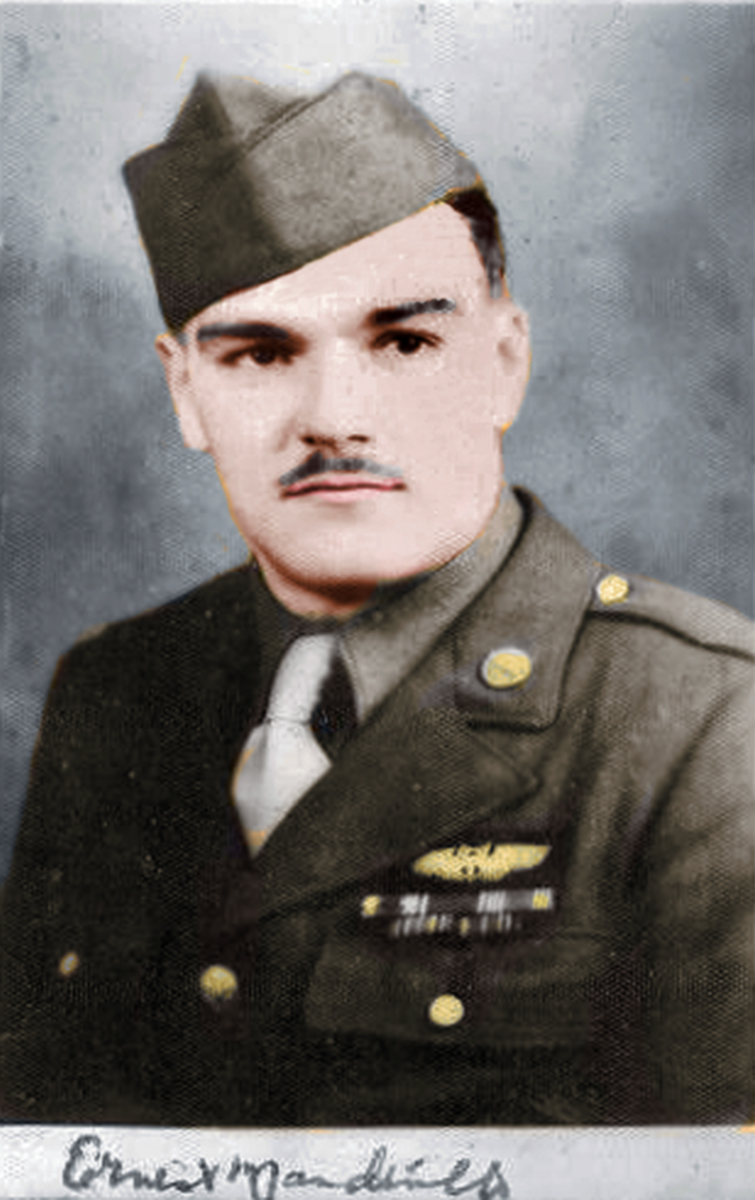

S/Sgt. Ernest Mandeville

.

.

.Click any picture or image to see enlarged.

Notes from daughter, Elizabeth Mandeville-Stryjewski ;

Dad was a radio operator and side gunner. My Dad flew 62 missions and was wounded only once. He got a piece of shrapnel in his hand, apparently it was pretty bad. My Dad also told us that the ground crew always checked the plane for shrapnel and kept the pieces as souvenirs. I know also that the plane was damaged so badly that they barely made it back to the coast of Englad, landing at a base near Land’s End, they couldn’t get back to the base in Bishops Stortford. The pilot was awarded a special medal for this. My father always said that the “MA” in the name of his plane was the pilot’s initials “M. A.”.

Thank you also for the message from Anson Courtright, the nephew of Milton. He says that his uncle got the Flying Cross for bringing his wounded crew and plane back. My father told me of one mission when their plane was so badly damaged that they couldn’t make it back to their base in Stansted and had to land somewhere near Land’s End instead. Perhaps this is the mission that Anson is referring to. My father was wounded, he has a purple heart, perhaps he was one of the wounded crew that Anson refers to.

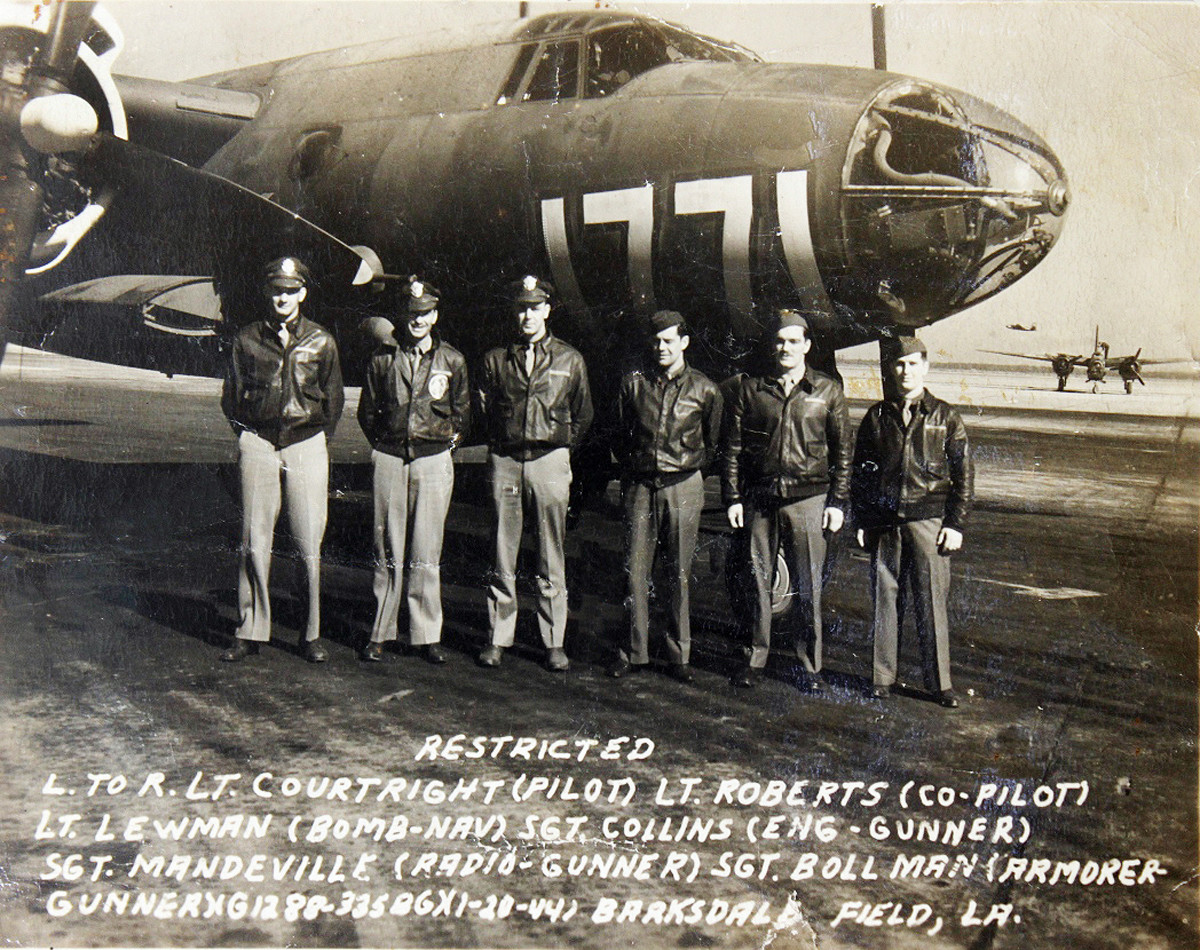

.Mandeville and company are pictured shortly after forming as a crew at Barksdale Field in Louisiana. Soon they were sent to the European Theater.

.

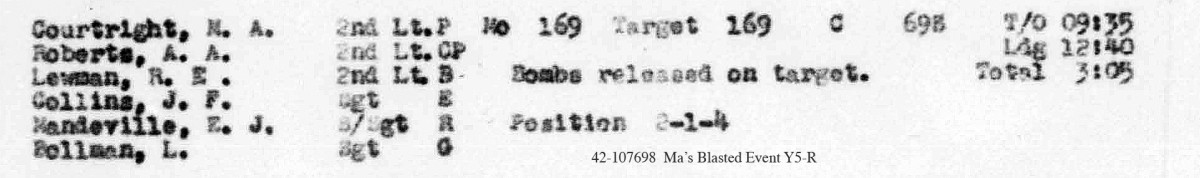

.42-107698 Ma’s Blasted Event Y5-R was the plane most used by Courtright/Mandeville crew. Pictured below is the plane with the ground crew that kept her airworthy.

.

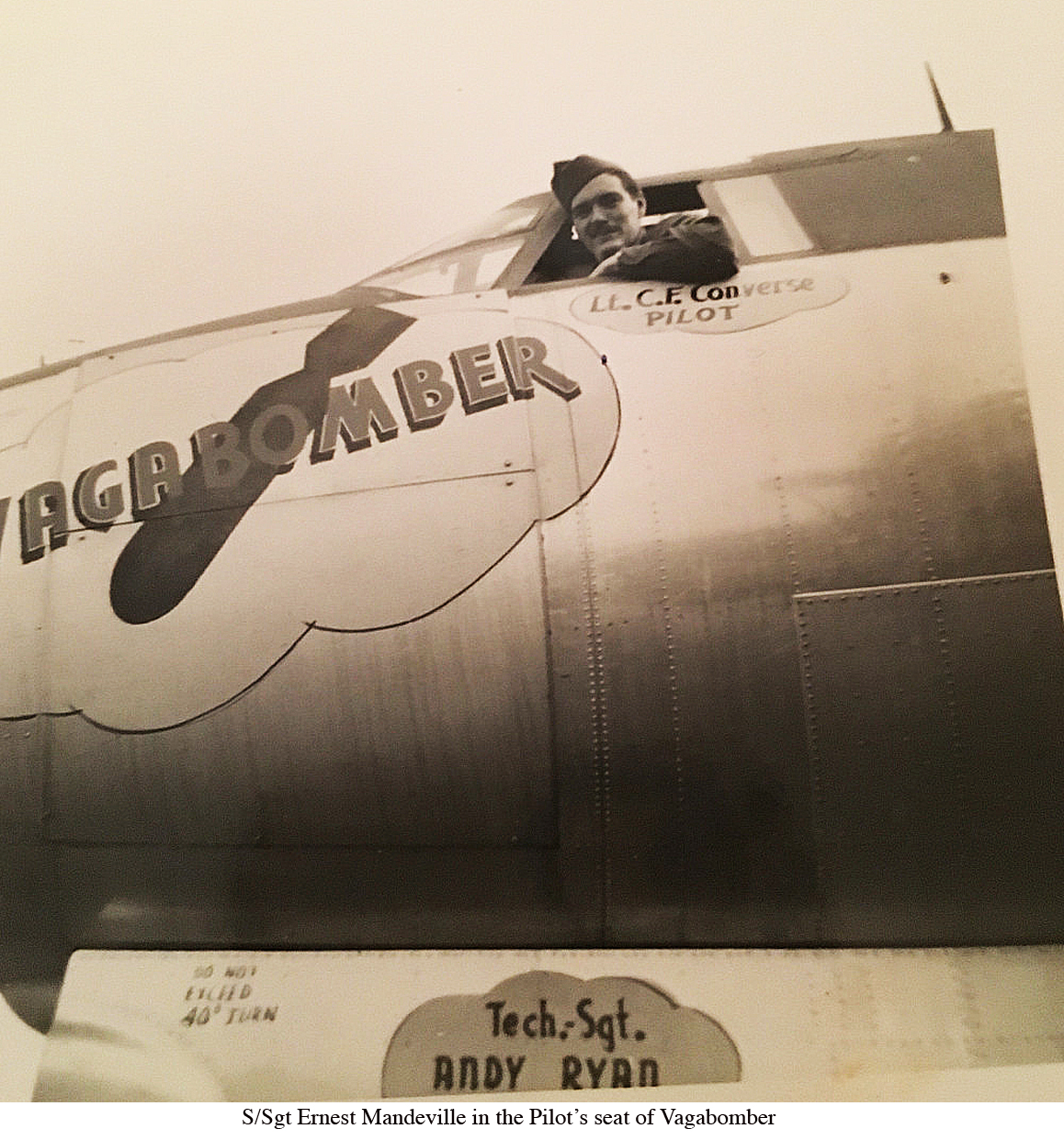

Elizabeth Mandeville-Stryjewski – On the back of the above, “Vagabomber” picture is written: “Mande and our ship. We miss ole M.A. he sure was a good M.A. to us Sept 1944.”

I’m thinking this is in reference to Milton A. Courtright. They were all getting ready to go home in Sept of 44, so perhaps they had flown their last mission at this point.

.

Also, on the same picture, Milton Courtright writes: “Courtright’s crew flew this ship on four or five missions, before we had a ship and crew chief assigned to us”.

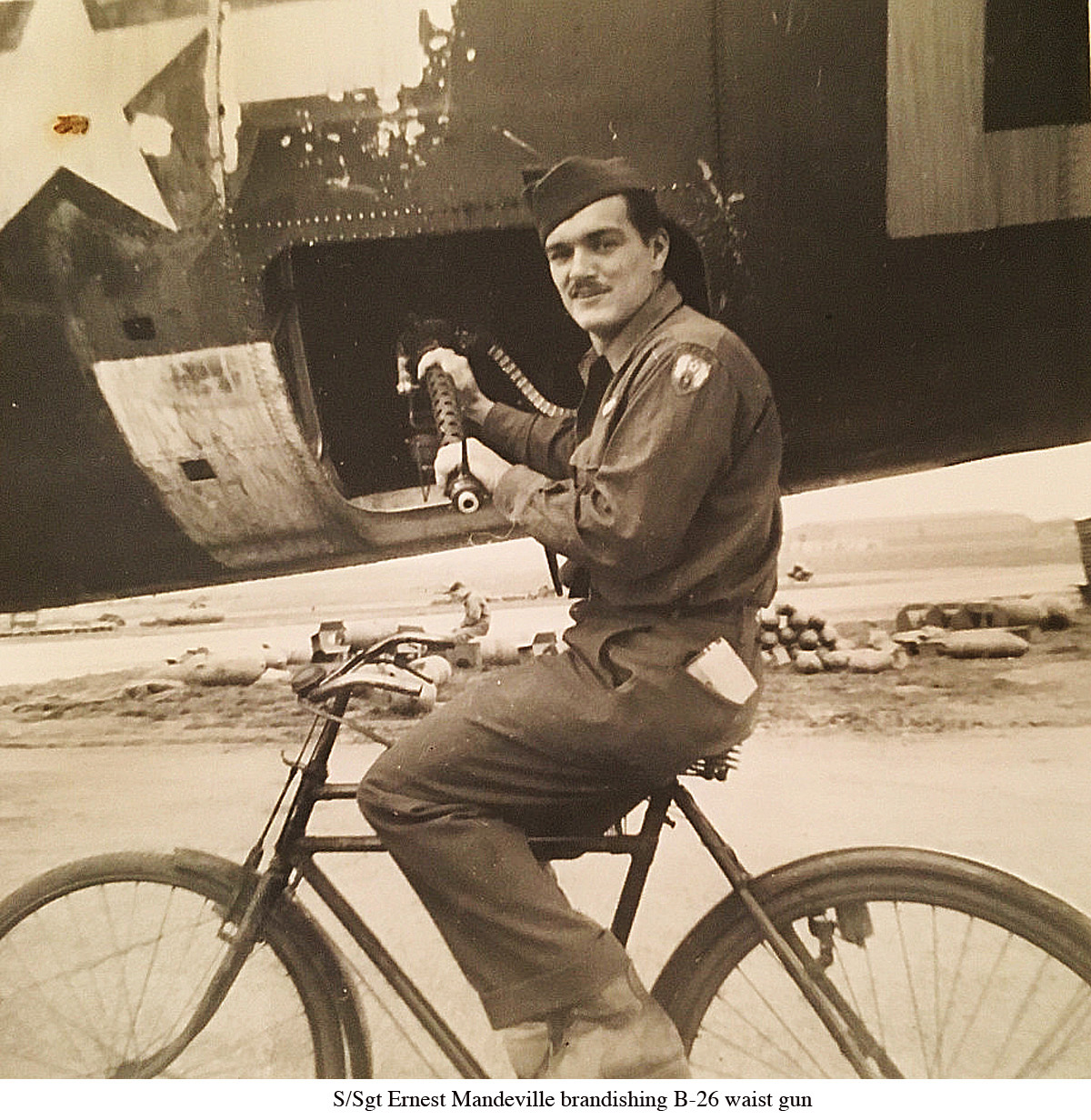

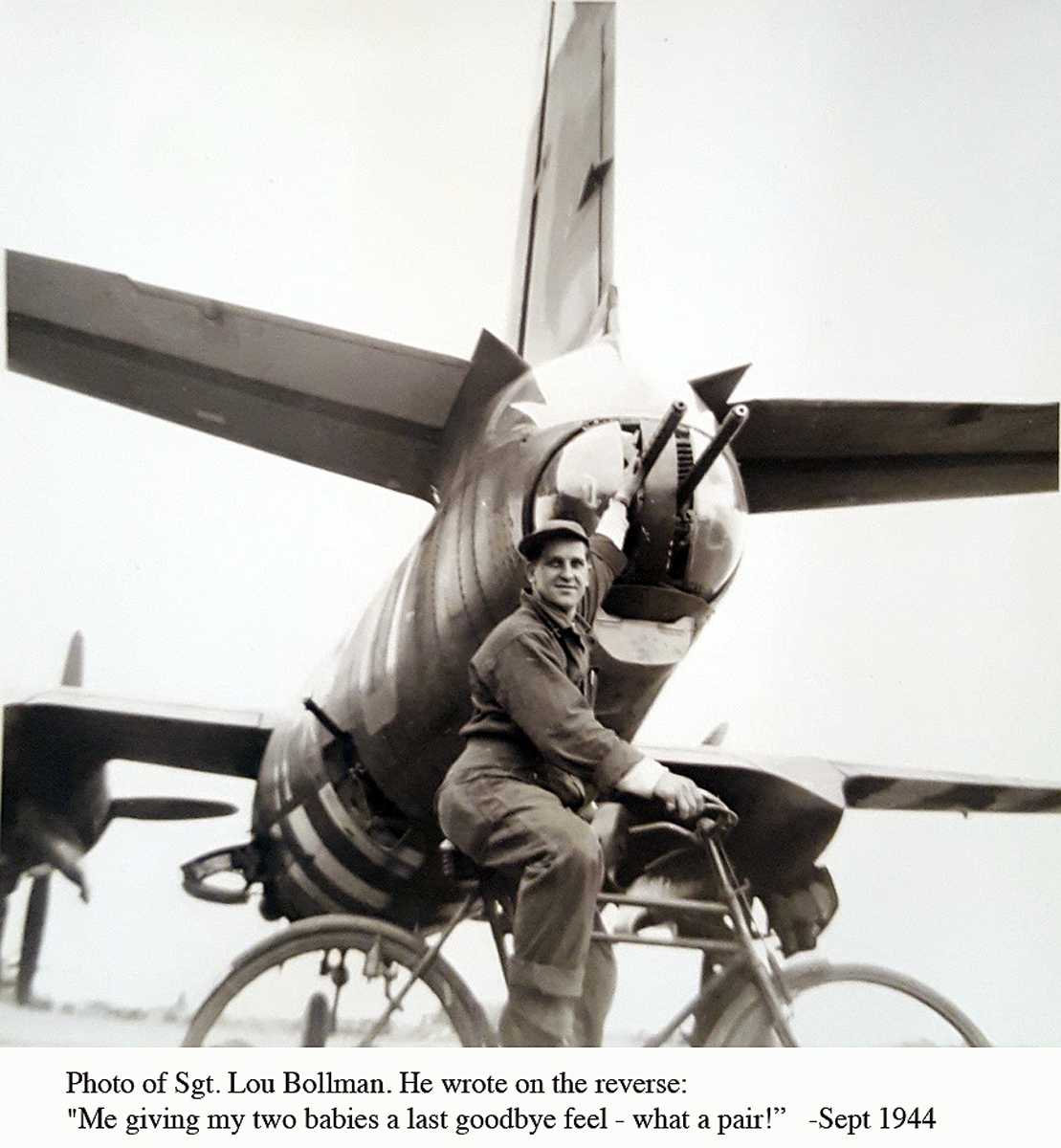

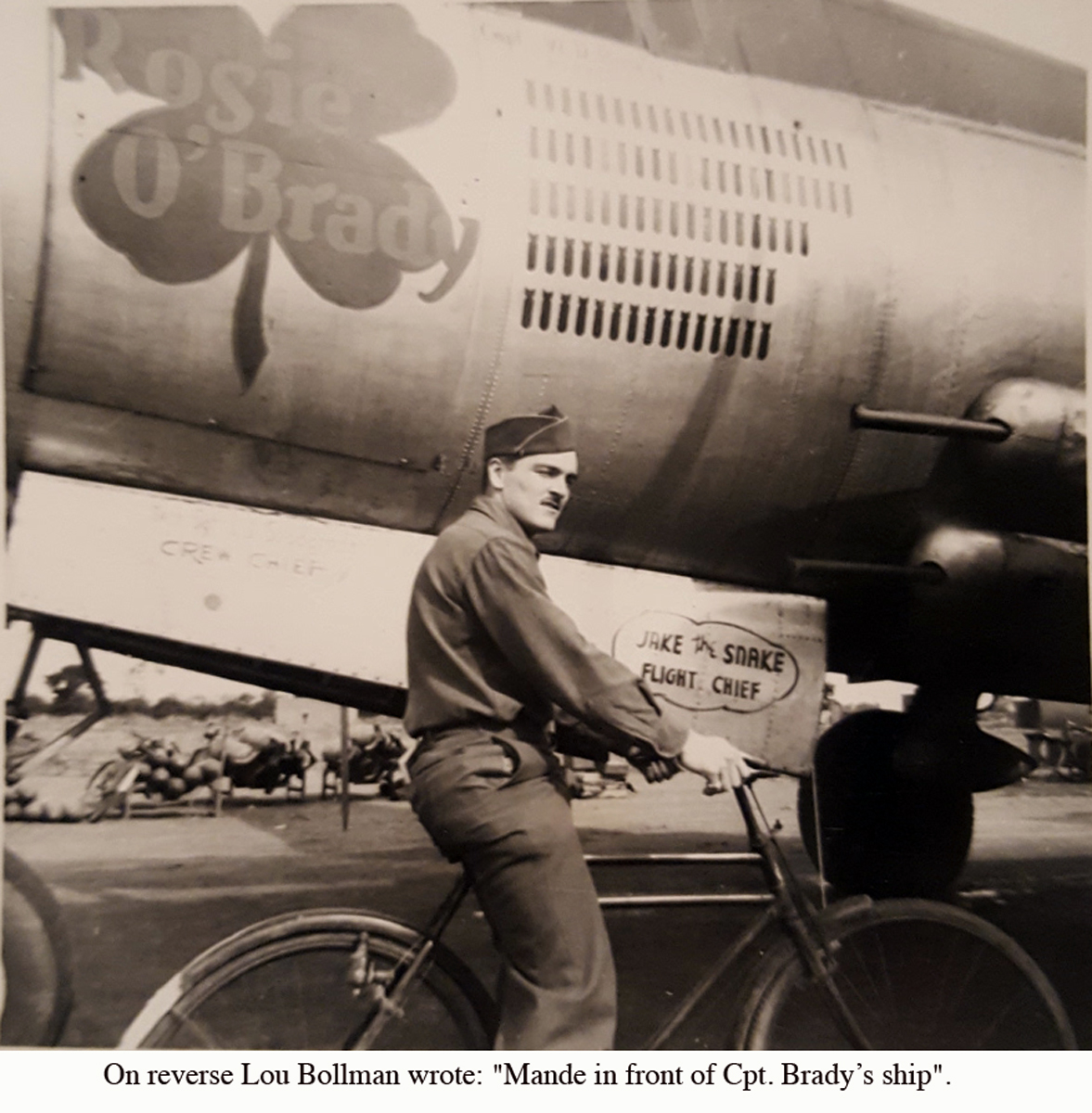

Elizabeth Mandeville-Stryjewski- “The above pictures of my father and Lou Bollman, the tail gunner of the crew. Lou has written on the backs of these pictures and refers to the Vagabomber as “our baby”, so I’m thinking that my father’s crew also flew missions aboard the Vagabomber, although I am SURE that he never mentioned it to me! My father’s nick name was “Mande”, so that is how he is referred to on these pictures.

Elizabeth Mandeville-Stryjewski- “The above pictures of my father and Lou Bollman, the tail gunner of the crew. Lou has written on the backs of these pictures and refers to the Vagabomber as “our baby”, so I’m thinking that my father’s crew also flew missions aboard the Vagabomber, although I am SURE that he never mentioned it to me! My father’s nick name was “Mande”, so that is how he is referred to on these pictures.

.

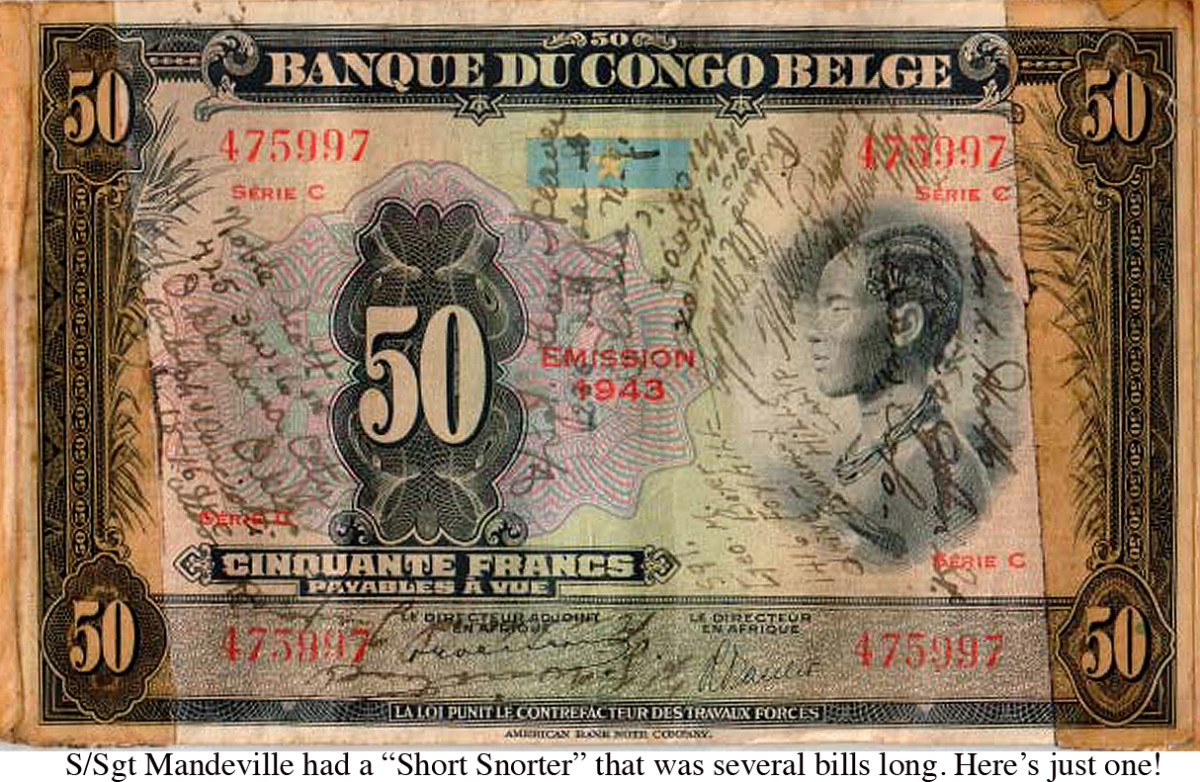

Elizabeth Mandeville-Stryjewski wrote about “Short Snorters” and the example collected by her father:

Although there are many theories as to the origin and meaning of the word “short snorter”, it is commonly believed to have started when early fliers (who flew dangerous missions) were seeking the comfort of a good luck charm. Dollar bills were easy to come by and easily kept folded in a pocket, so before a mission, fliers would pull out a bill, have each member of the crew sign it and return it to his pocket where it would be kept for luck. Regardless of when the tradition started, it certainly became very popular during WWII. Military fliers who were preparing to cross the Atlantic Ocean would pull out a dollar bill and have their fellow crew members sign it and these would be kept for good luck on the trans-Atlantic flight. As time went on, the tradition expanded to include all parts of the world. The snort snorter also became a good luck charm for not just aviators, but any soldier, even General George S. Patton kept one. The tradition also grew when the short snorter became used as an “ice breaker”. If one flier asked another flier to produce his short snorter, and he was unable to do so, it became tradition for that flier to buy the first round of drinks. Additionally, aviators would tape other bills to their short snorter, currency they collected through their travels, and have friends and acquaintances sign the bills as a remembrance. My father, a waist gunner with the 344th Bomb Group, did this and his snort snorter became quite impressive. He had the initial $1 bill signed by his fellow crew members, but then taped more bills to it, end to end, to form a “not-so-short” short snorter that is over 15 feet long and comprised of over 30 bills. It consists of currency from countries throughout Europe and North Africa. These are donned with countless signatures and addresses of other members of the 344th. An example of one of these bills is pictured. It is from the Belgian Congo and it is signed by (among others) Noble Scott of Oklahoma City. These short snorters are a personal piece of WWII history, each is unique and reflects the travel and social interactions of the owner.

.Click here to see the whole short snorter!

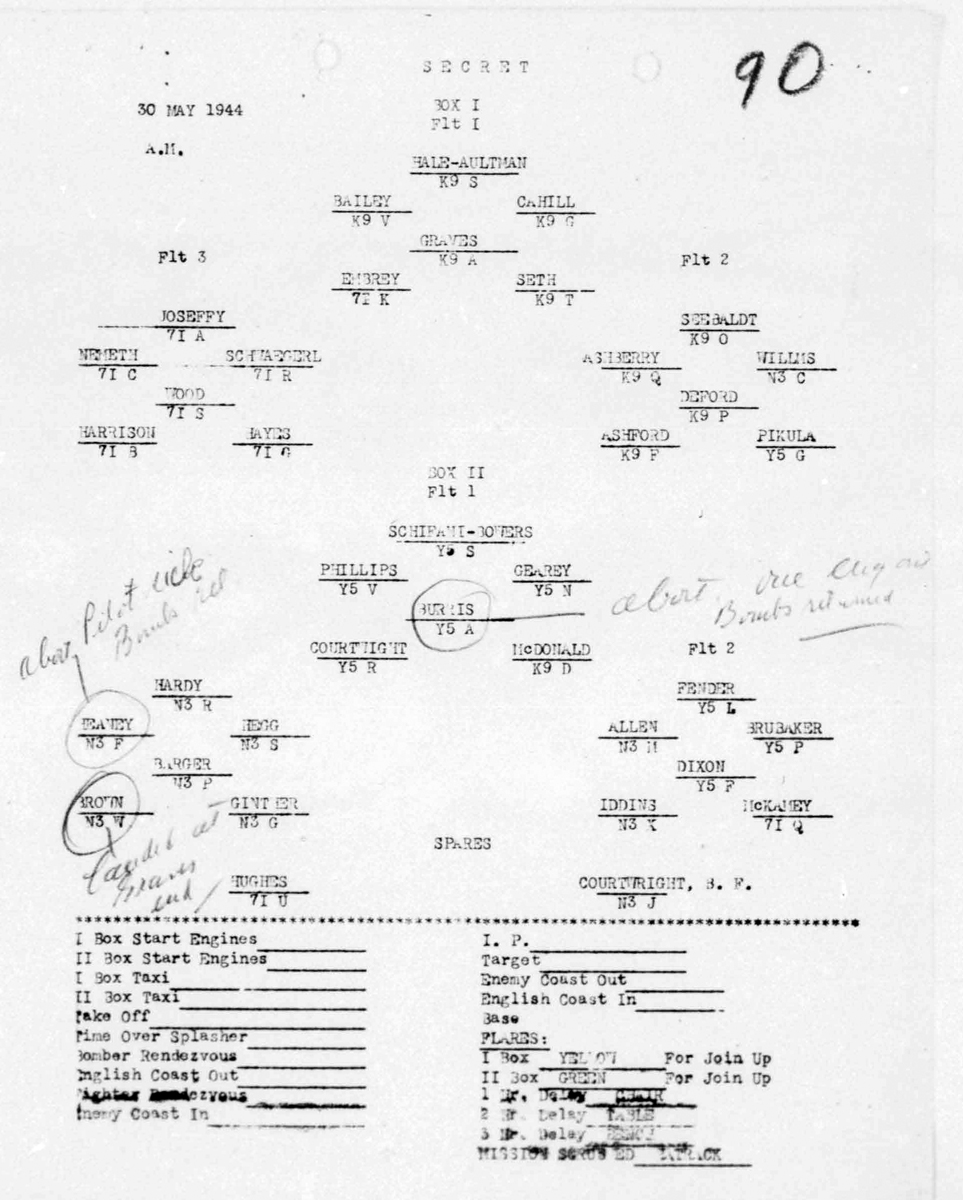

.Records were located regarding one of Mandeville’s earlier missions that took place on May 30, 1944. The 344th Bomb Group was sent out to bomb a bridge in Rouen, France. During the mission, seven planes were battle damaged but the results of the bombing were excellent. Below are the formation and load list for this mission.

.Note Courtright near the center of the formation (Box II).

Ma’s Blasted Event Y5-R was flown for this mission.

.

.

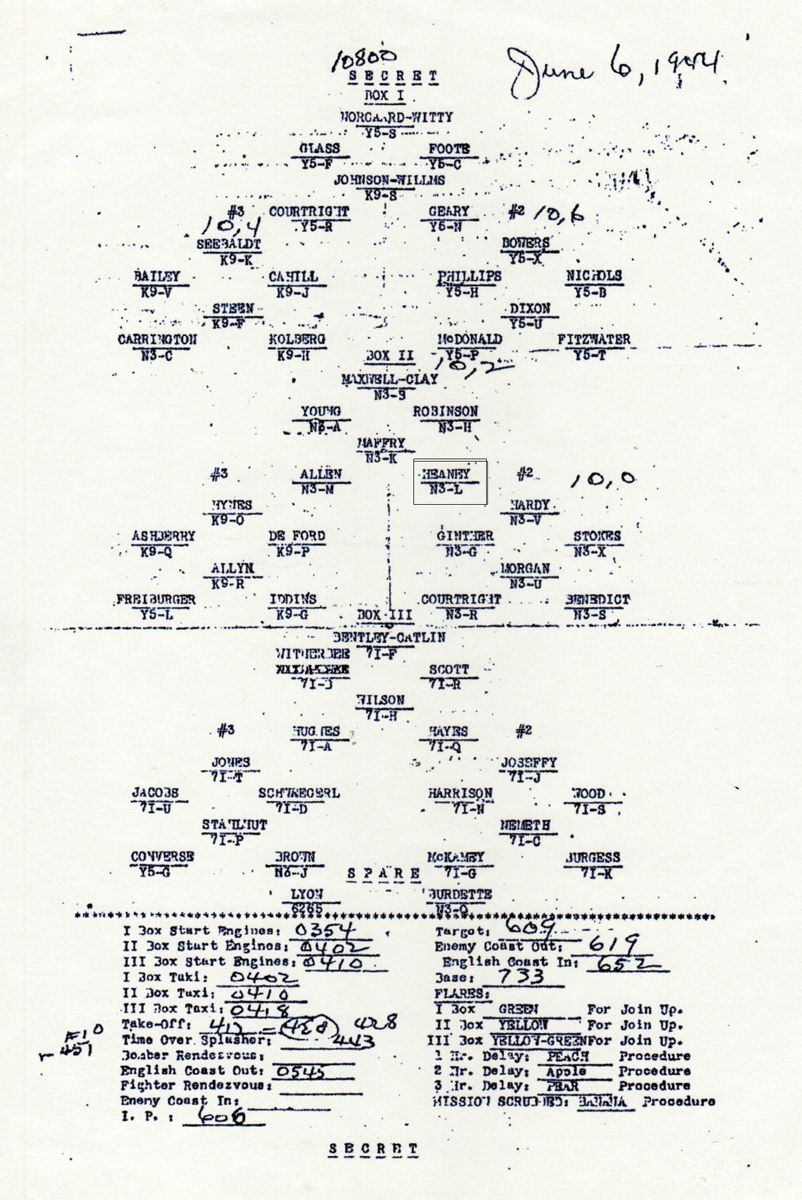

.S/Sgt Ernest Mandeville was part of the first bomb group to drop bombs on D-Day.

.

.Below: Formation diagram for the first D-Day mission. Note that Mandeville flew in Ma’s Blasted Event Y5-R for this mission. It was piloted by Courtright.

.

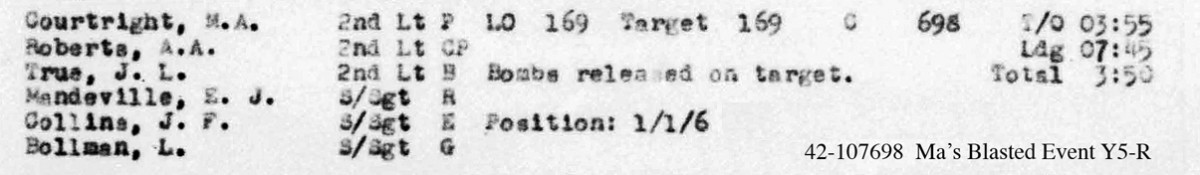

.Below: This load list indicates the crew for the first D-Day mission. Records show a discrepancy as to which plane was flown by Courtright/Mandeville.

.

.

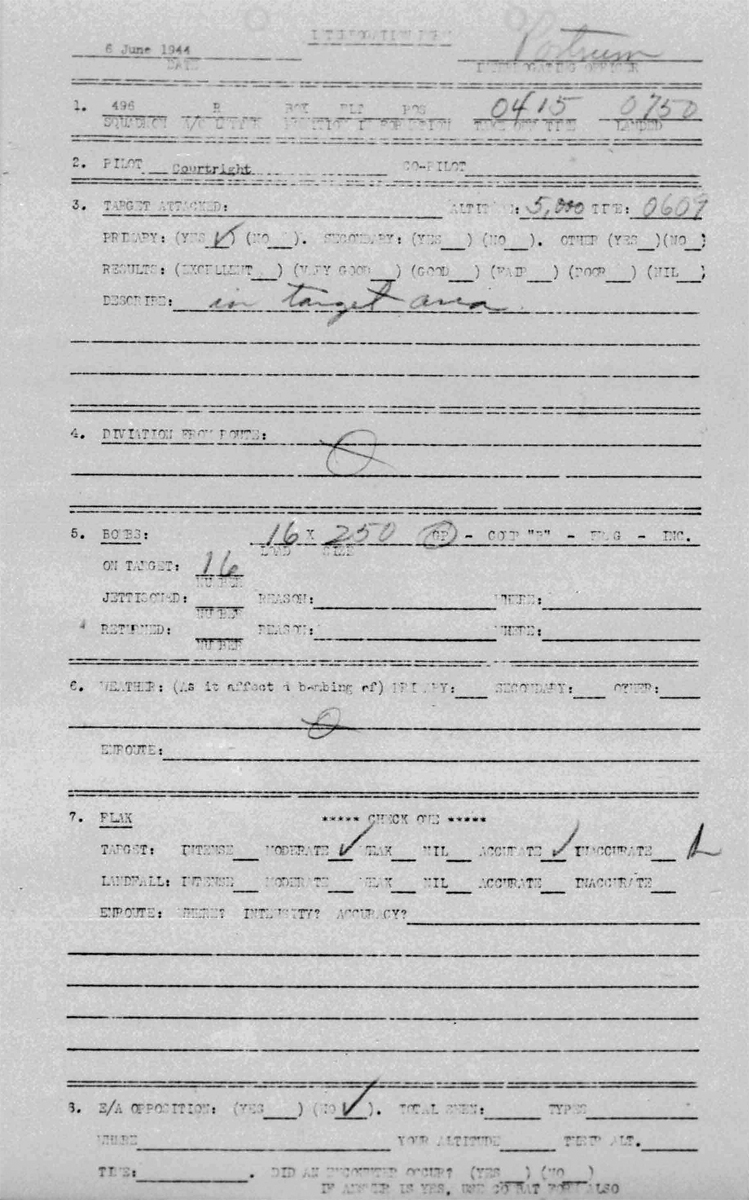

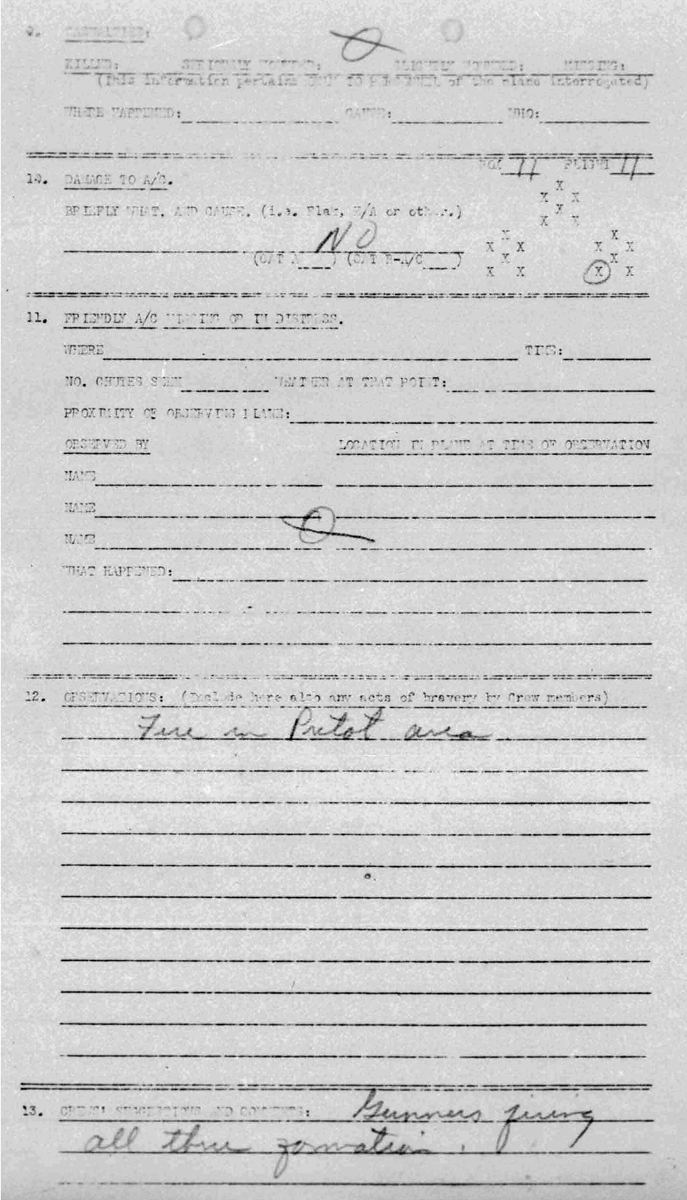

.Pilot Courtright was debriefed on the D-Day mission on the 2 page document below.

.

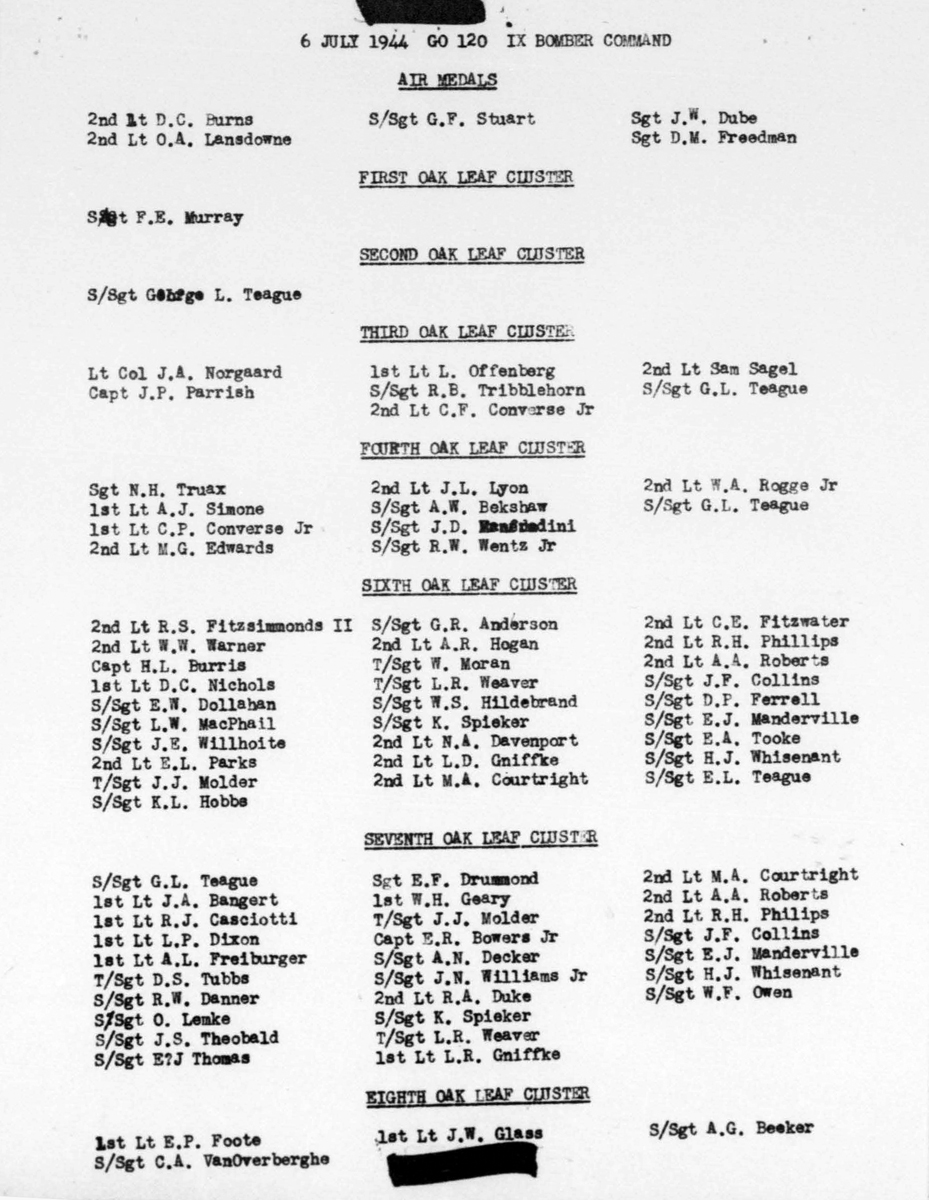

The document above includes Mandeville in receipt of the seventh Oak Leaf Cluster to be added to his Air Medal. These are awarded according to the number of missions flown.

.

This article first appeared in the December 2014 issue of the “Milk Run”, the official newsletter of the 344th Bomb Group Association

By Elizabeth Mandeville Stryjewski

My father, Ernie Mandeville, was a waist gunner aboard the B-26 “MA’s Blasted Event” in the 495th BS of the 344th BG. He and I have attended 344th BG reunions over the years but have not recently as his health has prevented it. Unfortunately, those same health issues prevented him from attending the 70th anniversary of the D-Day invasion in Normandy with my family and me this past June.

When we first scheduled our trip to Normandy, we did not even entertain the idea that we would be able to attend any of the events as we were sure they were reserved for government representatives, foreign dignitaries and other VIPs. One event which was open to the public that we did attend was a parachute jump by the Round Canopy Parachute Team near Utah Beach.

On our way there, many WWII era American jeeps, motorcycles, and trucks driven by people dressed in US Army uniforms drove along with us as we headed to a field outside Carentan.

On our way there, many WWII era American jeeps, motorcycles, and trucks driven by people dressed in US Army uniforms drove along with us as we headed to a field outside Carentan.

Nearly every house along the way flew an American flag. Upon arrival, I introduced myself to several of the groups of American GIs. It didn’t take me long to realize that not only were these people not American, they didn’t even speak English.

Nearly every house along the way flew an American flag. Upon arrival, I introduced myself to several of the groups of American GIs. It didn’t take me long to realize that not only were these people not American, they didn’t even speak English.

Women were dressed in 1940s attire and they mingled with soldiers of the Scottish Highlander Brigade, English infantry and American GIs (none of which spoke English).

Women were dressed in 1940s attire and they mingled with soldiers of the Scottish Highlander Brigade, English infantry and American GIs (none of which spoke English).

We soon found a group of “American” soldiers that had traveled down from Kent to attend the week-long celebration. Since their English was pretty good, we settled in with them and waited for the C-47s to fly over. They did a spectacular fly-by, some painted in D-Day stripes, others silver. Unfortunately the winds were too strong that day and the jump was canceled. I thought that would be the end of our participation in the events of that week, but I could not have been more wrong.

We soon found a group of “American” soldiers that had traveled down from Kent to attend the week-long celebration. Since their English was pretty good, we settled in with them and waited for the C-47s to fly over. They did a spectacular fly-by, some painted in D-Day stripes, others silver. Unfortunately the winds were too strong that day and the jump was canceled. I thought that would be the end of our participation in the events of that week, but I could not have been more wrong.

We were staying with a delightful French couple, the Cantels, just outside Caen and upon hearing that my father had taken part in the invasion, they took it upon themselves to help us celebrate and arranged for us to attend several events reserved only for VIPs. We attended a commemorative concert, complete with an orchestra and a 200 person choir in a 12th century cathedral in the nearby town of Falaise. After enjoying the concert on the night of June 5th, we headed to Benouville and Pegasus Bridge. Fireworks were scheduled to begin at Utah beach just after sundown. These were followed by displays at Omaha Beach then subsequently at Gold Beach, then at Juno and Sword beaches as the night went on, finally reaching Pegasus Bridge in the early hours for the morning of June 6th. What an honor it was to be at this place marking the 70th anniversary of the invasion. Following the fireworks displays, a band of highland pipers headed across Pegasus Bridge. Over the next few days, we found that many events opened their doors to us simply at the mention of my father’s role in the invasion. We were invited to the opening of the “Shots of War” exhibit at Le Memorial in Caen. This exhibit highlighted the work of photographer Tony Vaccaro from the 83rd Division of the American Infantry. The subsequent cocktail party gave us the chance to meet Mr. Vaccaro and the Mayor of Caen. Later in the week, we were welcomed to the town of Thoan where the mayor and local historian gave us a tour of a church which had been bombed during the invasion and lovingly reconstructed after the war.

Rather than feeling that the bombs had destroyed their church, they felt the bombing and subsequent restoration of the church represented their liberation from Nazi Germany and graciously accepted a photo of my father and his crew to display in the church. Everyone we met asked me to extend their thanks to my father and the members of the 344th. The entire week was like a celebration of America. This sentiment was reflected in something a total stranger said to me. A lady in a wheelchair recognized our American accent and she spoke to us through an interpreter. She told us that she was 95 years old and that even after 70 years, it was still good to hear that Americans were in France. We were so touched by our reception in Normandy, I’m sure if they could, they would all thank each and every one of you for your service, just as I do.

Rather than feeling that the bombs had destroyed their church, they felt the bombing and subsequent restoration of the church represented their liberation from Nazi Germany and graciously accepted a photo of my father and his crew to display in the church. Everyone we met asked me to extend their thanks to my father and the members of the 344th. The entire week was like a celebration of America. This sentiment was reflected in something a total stranger said to me. A lady in a wheelchair recognized our American accent and she spoke to us through an interpreter. She told us that she was 95 years old and that even after 70 years, it was still good to hear that Americans were in France. We were so touched by our reception in Normandy, I’m sure if they could, they would all thank each and every one of you for your service, just as I do.

.

.