Santo Endrizzi WWII Memoirs 344th Bomb Group 495th Bombardment Squadron

Click any picture to enlarge.

When I arrived in the United States in 1936 from Cavedago, Italy, I was fifteen years old and not a citizen of America. I always liked airplanes and wanted to join the Air Force but my father told me to wait until the government called me. In 1941 and 1942, I was working for the Wurth Electric Motor Company at 141 Grand Street in Manhattan. They supplied all the motors for defense factories. It was a year and a half after I started that I was first called to serve. My boss asked for a six month deferment as they needed me in the factory. He tried for a second extension but was told that the Army needed me more. In October of 1942 I was drafted and accepted into the Army.

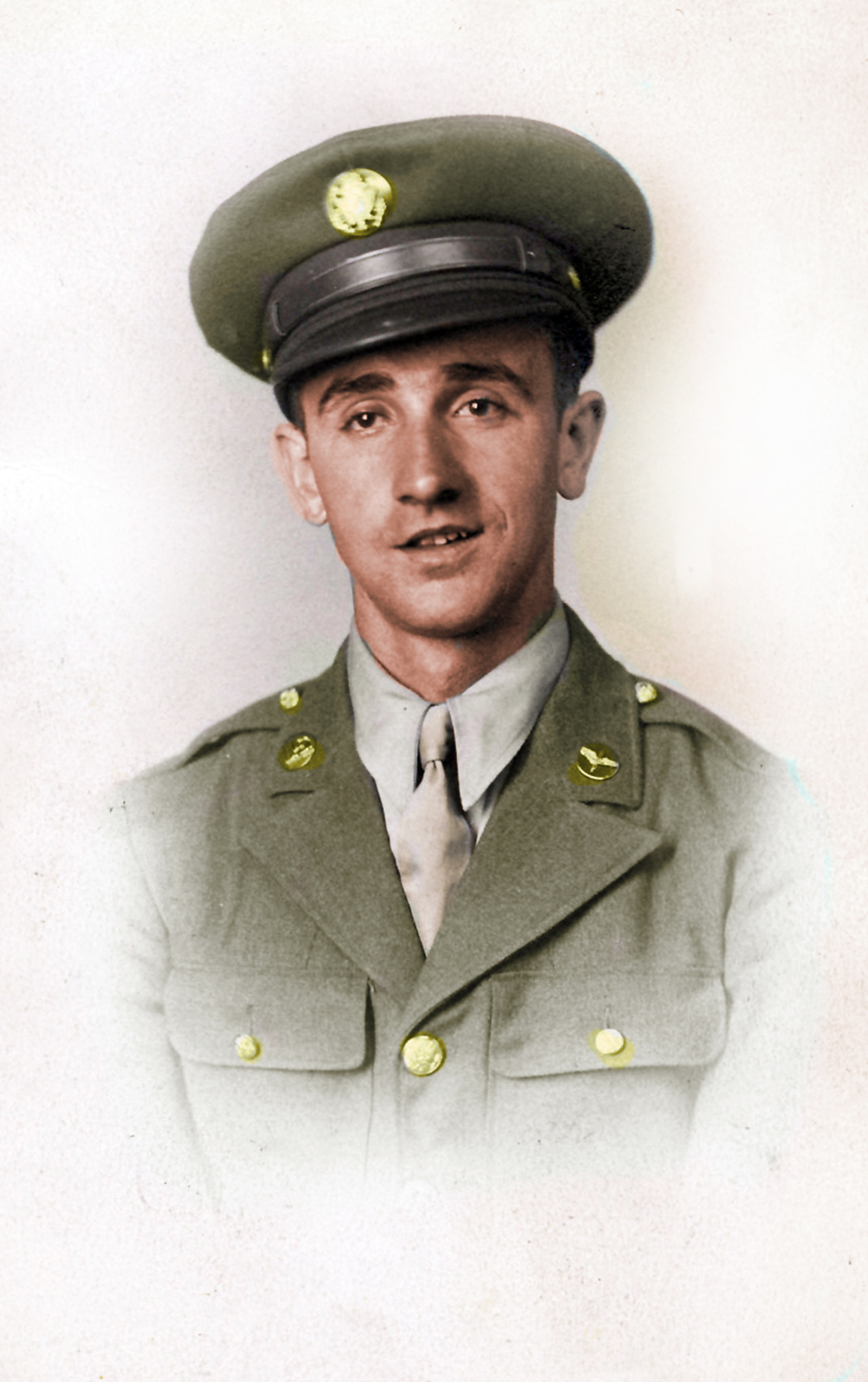

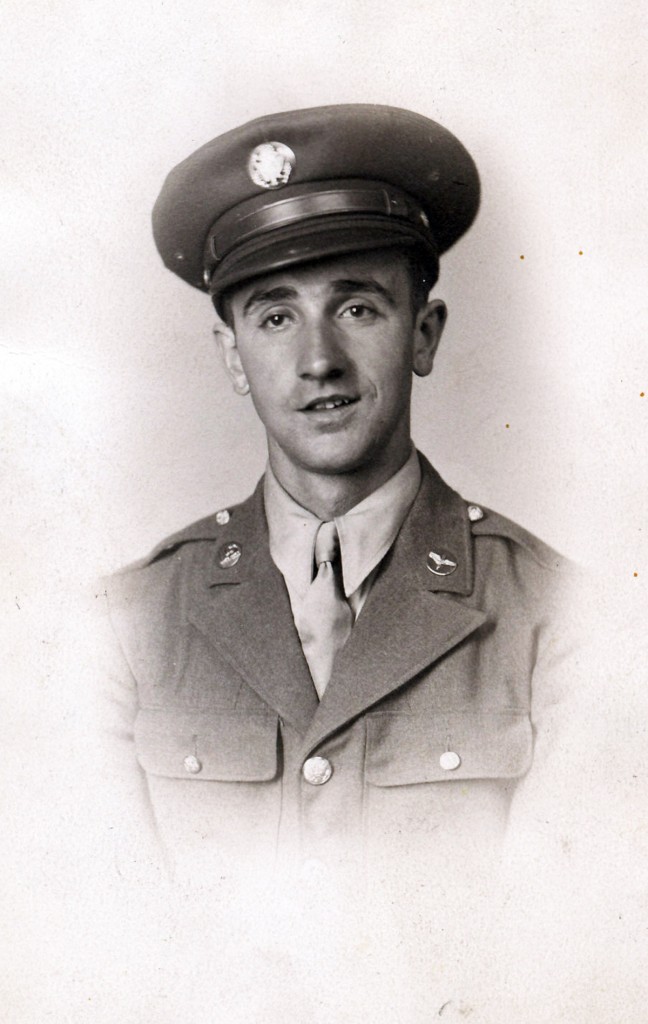

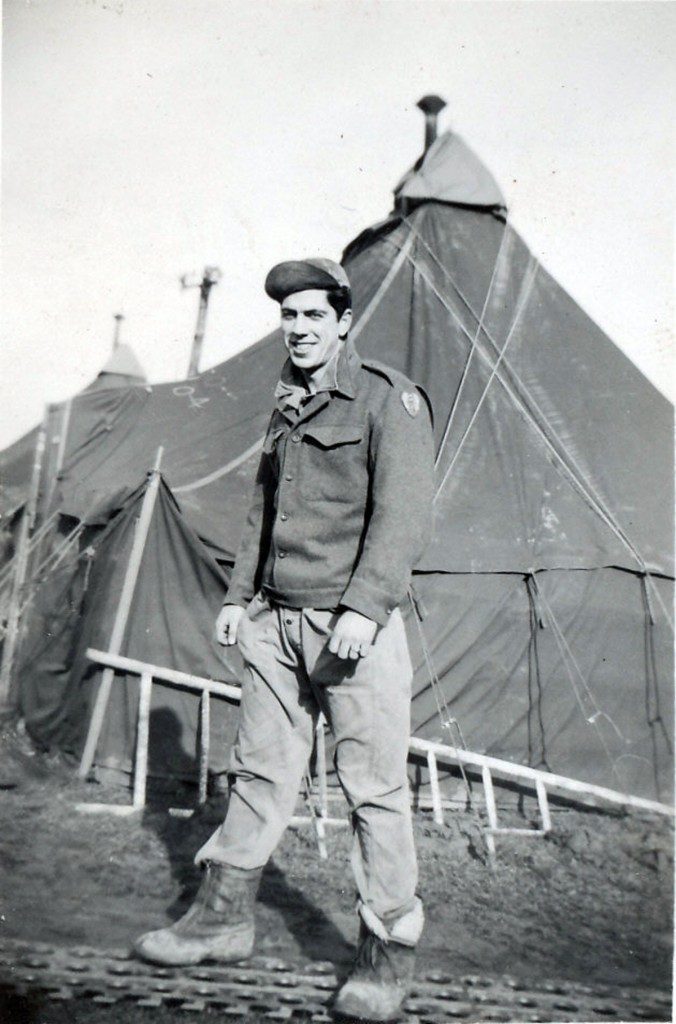

Picture of Santo taken at Atlantic City, N.J. During his basic training.

.

The first stop was Governor’s Island where I spent the entire day having my physical exam. There I was asked if I liked girls or boys. The next stop was Camp Upton on Long Island, NY (close to Stonybrook, NY). Here I received my new army clothes and inoculations. I received my dog tags and noticed that my father’s name, Donato was spelled incorrectly, Danado. We remained here for two weeks. We took turns having KP duty and we learned how to march. One day while marching early in the morning, I decided to smoke a cigarette. The Corporal in charge took me out and assigned me to KP duty. The Corporal gave me a huge load of pots to clean and said when I was done I could leave. But he brought another load of pots to clean! Then I was done. Another time we had to clean up the area where we smoked picking up all the cigarette butts in the dark.

.

After that they put us on a train. We had no idea where we were going. When we saw the skyline of Atlantic City we were happy as this meant we were going to be in the Air Corp. I must have done well on the tests, pretty good for only being in this country for six years. My experience with electric motors really helped!

.

We moved into the St. Charles Hotel in Atlantic City to a room on the 10th floor facing the ocean. We rose at 5 am for a short arm inspection. This is a check of one’s private area to see if you had any white discharge. If you did, you were classified as having a sexually transmitted disease. We were also shown movies depicting the sickness you could get from women. Everything at the hotel was blacked out, no lights anywhere, as the enemy submarines might be in the Atlantic Ocean. Every day we shaved in the dark. I stayed there for five months doing guard duty and marching to the rifle range for shooting practice. It was a very cold winter.

We would march the entire boardwalk with a full pack in the pouring rain or sun. In the hotel there was a barbershop where all the GIs had to get the same crew cut. The barber was Italian and he invited me to his house for Christmas. It was nice to be with a family for the holiday. The food was great, much better than the Army chow.

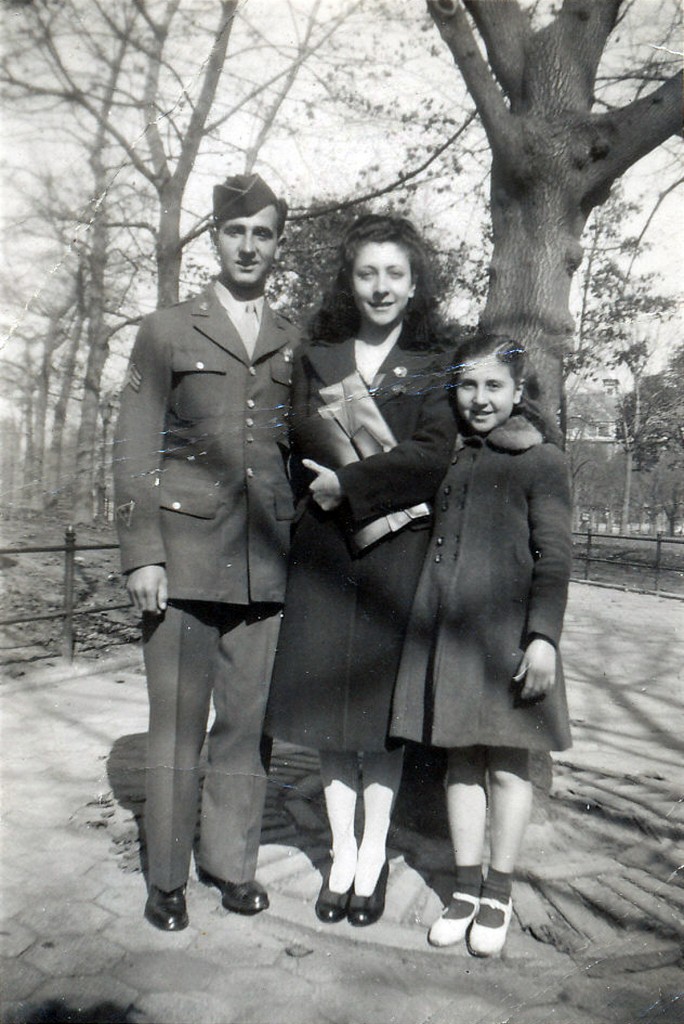

While at the St. Charles Hotel, my parents and sisters would take the train from NY and come to see me. I was so happy. We would go out for a nice dinner and then they would take the train back to Brooklyn.

.

We moved to the Ambassador Hotel also on the boardwalk. Glen Miller played for us in the mess hall. While I was there the Sargent kept calling me in and asking me if I wanted certain positions. Because I knew languages they wanted me to be an interpreter. Since I could ski, they wanted to place me in the Alpine unit. When they learned I could play music, they wanted to put me in the band. Since I had worked for the motor company in NY, I always replied that I wanted to attend airplane school. Finally they sent me, along with a few others to Goldsboro, North Carolina to Seymour Johnson Field. I was assigned to the barracks. The guys that were already there were career men.

Here I learned all about the airplane: structural, electric, hydraulic and especially the engines. By the time the program was over and I graduated from mechanical school, I knew everything about the plane. We did our bivouac in the woods practicing working on the planes. One day a thunderstorm came. We all stayed under the wing of the plane. The next class near us did the same thing. Sadly, lightning struck and that class of twenty men were all killed.

After finishing mechanical school I was accepted into gunnery school and sent to Fort Meyers, Florida. This was July 1943 and it was very hot down there. We did all kinds of shooting on the ground first. Then I had my first flight on an AT6 plane. The pilot was in front and I was in the back with a 30 caliber machine gun. We practiced over the Everglades shooting anything we saw.

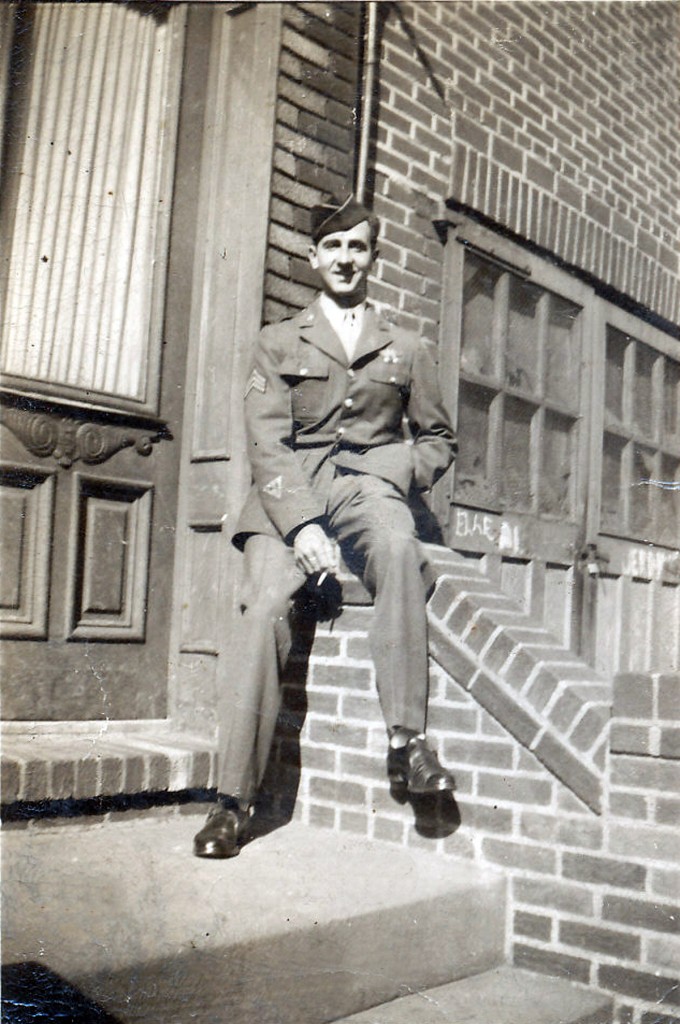

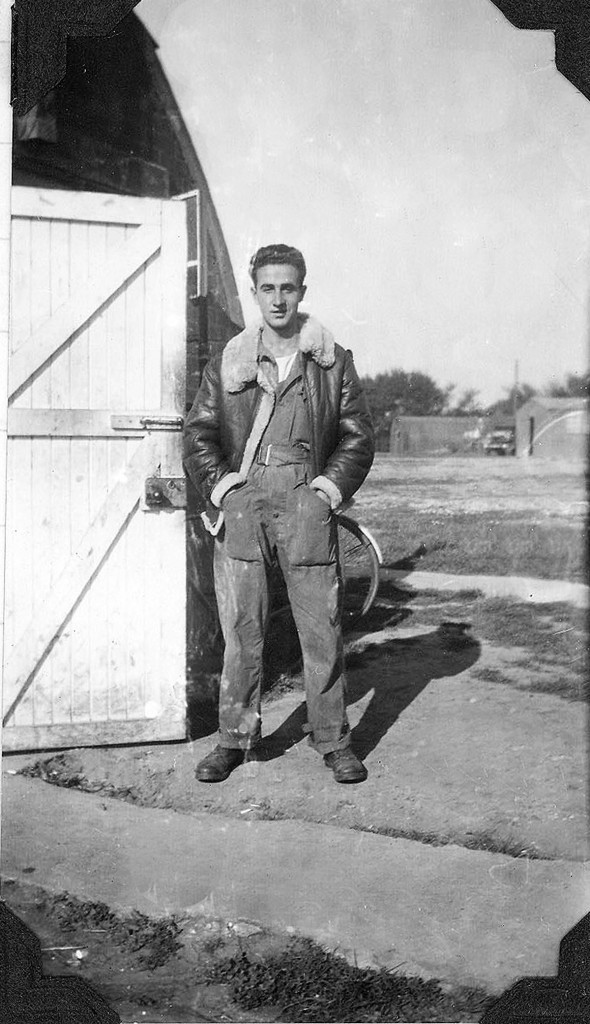

The next plane that I flew in was the B34. The whole class of ten went up in one plane and had to shoot at the target pulled by another plane. All the bullets were painted different colors so that each fellow knew if he had hit the sleeve (target). We finished and graduated, received our wings and had our photo taken with our flying clothes, a helmet and leather jacket. I had earned the rank of Sergeant.

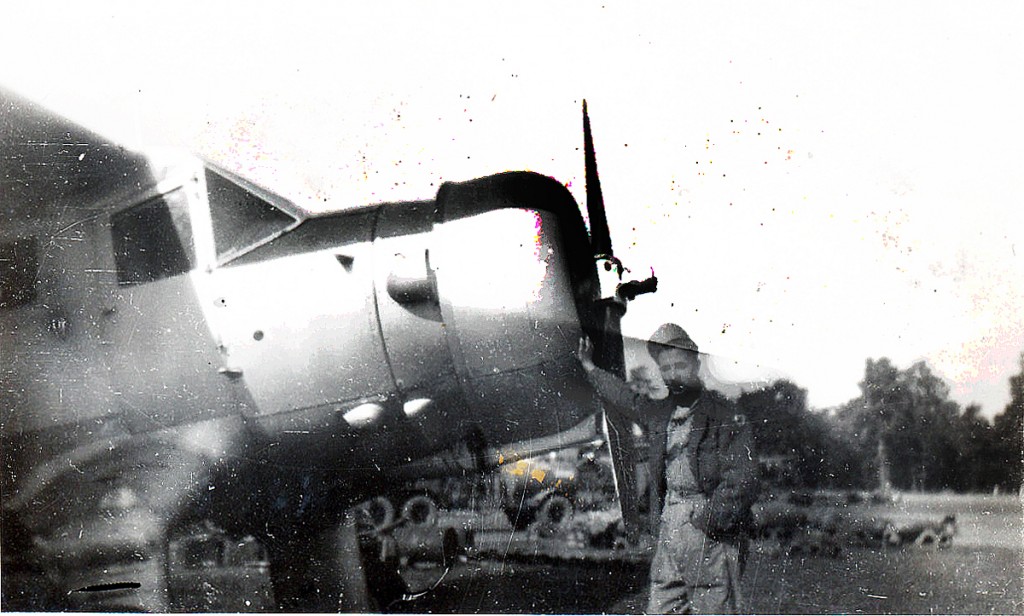

From Fort Meyers we were sent to Lakeland, Florida and assigned to the 344th Bomb Group 495th Bomb Squadron. There we practiced bomb drops and straifing everyday on a B26 over the Everglades. The Martin B26 Maurader had a bad reputation. The saying was “One a day in Tampa Bay”. Its nicknames were The Flying Widow, The Flying Coffin and The Flying Prostitute. The first pilots did not have enough experience to fly this plane. The B26 had a big fuselage and short wing span. You had to take off and land very quickly.

My job was flight engineer and I only remember my pilot, Lieutenant Howard Fender, a West Point graduate and I am proud to say that he was the best. Every day we went out and dropped twenty bombs one at a time to the three circles in the Everglades. I used to tell the bombardier where it dropped, 12 o’clock first circle or 3 o’clock second circle and so on.

.

Flight engineer duties were to pre-fly the plane. That meant going into the cockpit, keeping the brakes on and with blocks under the weels, run the engines up to 2000 rpm and check the mag needles to be certain they worked. Then the pilot would come and ask how the pre flight inspection went. We would then take off. I sat between the pilot and co-pilot with an opening at my feet where I could see the nose wheel still down on the runway. I would say a prayer till the wheel went up and the opening closed. At 12,000 feet we would start dropping bombs.

“Second from left is Santo, my friend Guerino Viola also from Brooklyn, N. Y. with his two friends and we are setting on 2000 bombs!”

.

After we dropped all twenty bombs, one at a time, down to straif and practiced with all the guns we were done for the day. This exercise took about four hours to complete. My spot was the turret with two fifty caliber guns. The tail gunner also had two guns. The radio man had the waist gun. The pilot had four fifty caliber guns, two on each side of the fuselage. He had a button on his controller. Sometimes the bombardier also had a fifty caliber in the nose.

After finishing practicing in Lakeland we were sent to Hunter Field, Georgia and waited to be assigned combat duty with a new B26. One day a group of us decided to go to Savannah, Georgia. One guy named English decided to leave our group and buy a bottle of whiskey to celebrate. When he left, he pointed to a car and said he was going to steal that car. We thought he was joking. We returned to camp and later when English returned he was wearing a neck brace and was accompanied by a guard. English just gathered his possessions and was escorted out. We never saw him again.

Left to right: sister Augusta, sister Albina, Santo, mother Angelina, sister Josephine,and sitting sister Ada.

.

I had a leave to go home to see my parents and sisters. It was in January 1944 and I was dressed warm with my O.D. (very heavy winter clothes) and a very warm coat but I was extremely cold. Living in the south thinned my blood! While home I talked with my father who suggested that I should become a mechanic rather than fly. This would give me a trade after the war was over. On my return I talked to my pilot and told him I wanted to become a mechanic. He was sorry to lose me but there were many guys that wanted the job as it had more stripes and paid more. I was placed with my crew chief, Iverson and together we took care of the B26. I am proud to say we never had an abortion.

Shortly thereafter we left for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. We stayed there about a week and then we were put on a small boat that took us up the Hudson River to the Queen Elizabeth. We approached from the rear of the ship and were in awe of its beauty. Eight of us were assigned to a beautiful cabin with all the amenities, of course with additional cots. There were a total of 18,000 soldiers on board. It was February and the Infantry were sleeping out on the open decks.

The first announcement made was for volunteers to serve food to the English gunners who were on the ship to defend it from the German planes. There is a saying in the Army to never volunteer for anything but one day I did volunteer and it was the best thing I ever did. This duty gave me three meals a day and the privilege of a red pass that enabled me to go anywhere on the ship I wanted. The others had to remain downstairs and had only two meals a day. Whenever I could I would bring down food to them as they were always hungry.

We zigzagged all the way to Scotland without any escort. We watched those English gunners practice with the guns and be prepared for any enemy planes that might show up. It took us only five days to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

.

When we landed in Scotland, it was February and we were all delighted to see such beautiful green grass. We could see some damage to buildings from the bombings. The ship could not dock because there wasn’t any port big enough. They put us in small boats sitting between each other’s legs as they took us to shore. We went right on a train and down to Bishop Stortford where we found snow. Fortunately we were housed in Quonset huts with a stove.

.

The weather in England was cloudy, not good for flying. We lost two planes as they collided in air and no one survived. I remember on the first bombing mission near Paris we lost half of the planes in the group. It was no picnic flying without escorts. Soon we got the P47, P51 and P38s and our B26s then had help.

The first thing they made us do when we arrived in Bishop Stortford was to build a fox hole. That same night we used it! I could see the swastikas on the planes. The 90mm guns shooting at them and metal from it made noise as things hit the iron roof on the huts. After a few times using the fox holes, I started sleeping right through the bombings in my bed.

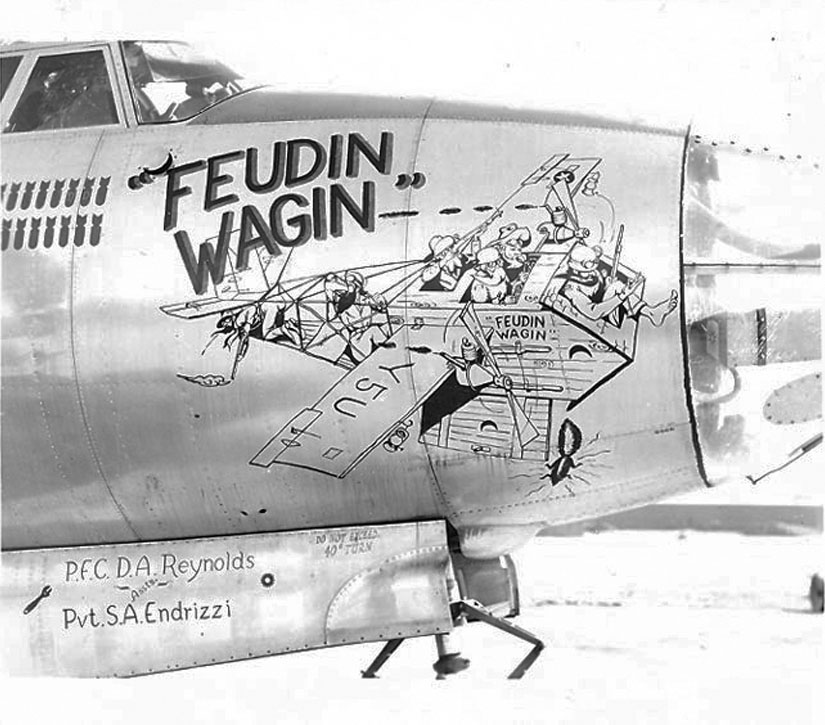

The 344th Bomb Group flew its’ first mission on March 6, 1944. One of my planes was called the Feudin’ Wagin. We bombed the airdrome northwest of Paris with fair results. We lost quite a few planes and men. The next day the 344th bombed air fields northeast of Paris. This was a huge success.

On my days off I used to take the train to London to see a friend of mine, Guerino Viola who was in the army. He was an interpreter. We had many Italian prisoners captured in Africa and Guerino used to cut out bad words from their letters that went to Italy.

Guerino introduced me to another paesan in London, Frank Ferrari and his family that came from the same part of Italy that I came from. To this day I am still in touch with Frank and his wife, Cesira and two of my daughters and a granddaughter have met them. This family adopted me and treated me very well. Frank’s mother made the same food that my mother made, polenta and pocio, a veal stew. They lived around the corner from a BBC radio station. Their neighborhood was not bombed. However, everything around St. Paul’s Cathedral was bombed. They told me a two thousand pounder came down at it but it did not explode.

We used to go dancing in Covent Gardens with beautiful music from the Glen Miller Orchestra. I met a girl there who was very nice to talk to and dance with. When our ODs (wool suit) needed to be cleaned we would dip the suit in and out of one hundred octane gasoline and then dry it on the clothes line in the wind. Good as new.

The summer days in England were very long, only a couple hours of darkness. Our planes sometimes would fly two missions in one day.

My friend, the interpreter, lived in London and his place was hit by the V1, a German plane with no pilot. Fortunately he was out that night. I was on top of the wing filling up the gas tank on my plane and saw three V1s coming over the tree tops just above me. Lucky for me the motors were still running and they were on course to London.

One day I was walking in the park in London with my interpreter friend and a V1 came over our heads. It hit a row of houses and exploded. Once a week I went to London and every time I would see a new place that was bombed. It was a good thing that the London subway was deep underground. There on the platform you would see people sleeping. They were safe from the bombings there and most had no where else to go after their homes were destroyed by bombs. After the V1 came the V2 rockets, also without pilots. They were bigger and had more power and caused more destruction.

One day men were told to paint black stripes on the fuselage and on the tops and bottoms of the wings on all our planes so they could easily be identified. The Commanding Officer told the flight crew to shoot down any planes without stripes. We didn’t know it but the invasion of Normandy happened the next day, June 6, 1944. My commanding officer flew one of the first flights to bomb the coast of Normandy the night before the invasion.

Bishop Stortford was the nearest town and many GIs met girls. There were plenty of weddings with English brides. The guys were getting married left and right because they were afraid they were going to get killed. If they were killed in action, the widows would receive $10,000.00 in insurance money.

To catch a GI awol they made a 12 o’clock curfew. I was with one of my buddies who happened to get sick. I could not leave him alone and was trying to help him but we were picked up and put in jail in the town pub’s basement. Around two in the morning I called the guard and told him that my friend had a scheduled mission that morning. He let us go and we walked back to camp. In the morning we had to face our Major. I explained the situation and everything was okay.

Every day while working on the plane after it returned from a mission I would listen to the radio and hear Axis Sally talk to us from Germany. She would say “Did you get enough from us today? Tomorrow we will be waiting for you again.” She would even know the outfit number. She played American songs and would say ” Do you miss your wife or girlfriend in America” trying to make us homesick and lonesome.

In England they served beer warm and many of us got sick. The latrine was a bit of a walk away so you can imagine what happened all over. The food wasn’t too bad. We became used to powdered eggs and milk and S.O.S. (shit on shingles).

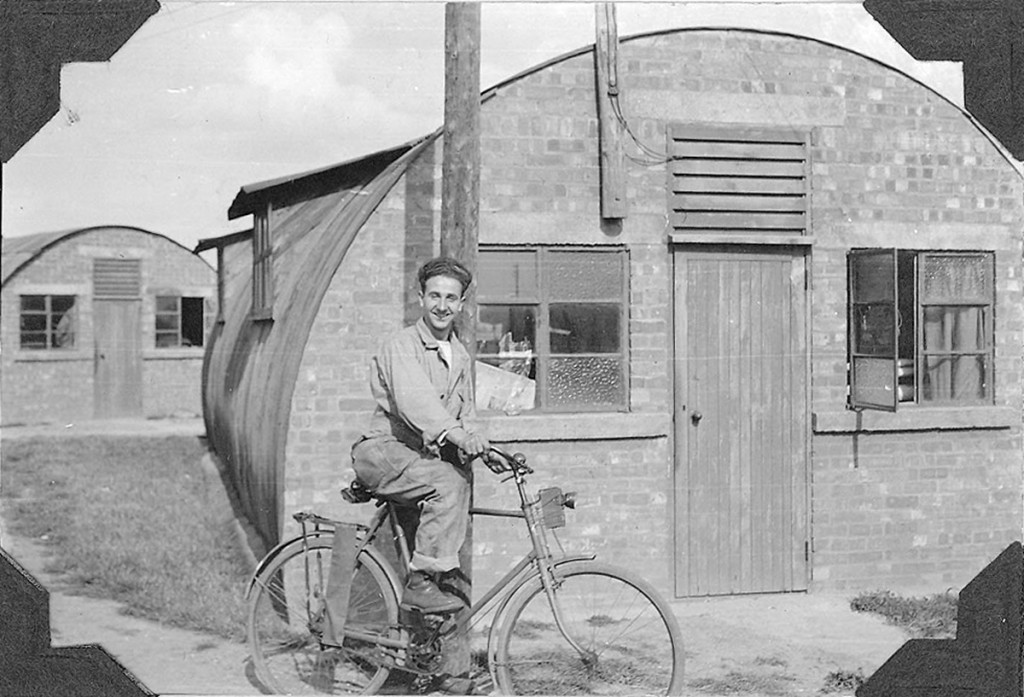

Every soldier was issued an English bicycle so we could get to our planes on the runway in a hurry. We could also use it on our day off and see the town nearby or ride in the beautiful English countryside. I went all over with my bicycle.

.

In the fall, September 1944 we put our bicycles and baggage on a C47 to be flown to our next stop Pontoise, France. We landed on an all metal runway because the original runway was full of craters from our bombing. We soon found out that our sleeping quarters were tents with muddy floors. We settled in and did the best we could. All the airplane hangars were bombed out. The only thing that was intact was the underground place for each plane. We used to cook our “C” rations and practiced carbine shooting. After a time we moved our tents in back of the town of Janicouer on top of a hill. We put a floor in the tent and a glass on top of the entrance to let light in. There was a coal stove in the center. Four of us spent that winter pretty comfortably and we were warm.

It was here that I first tasted champagne. It was sweet and went down so smoothly. I drank so much I became ill. When I returned to camp I could not find the entrance to my tent.

Opposite me in my tent was a sergeant by the name of Mack. He was checking his Tomson machine gun. I asked him “Please do not point that gun at me!” As he lifted the gun up, it went off over my head. I was really lucky to be alive. Mack had been sure the gun was not loaded. He was stunned.

A woman in Janicouer would do our laundry. Mack and I called her grandmother and she so enjoyed our visits to her home. We would play little tricks on her and we all had great laughs. One day I put a cup of water above the door and when they opened the door the water fell on their heads. For another trick I had her sit on the floor and put a small puddle of water between her legs. I gave her two knives and told her that she should move the knives up and down and in between moves I would dry up the water. That was not the plan. Instead, I grabbed her two ankles and pulled her right over the water and it dried up. She laughed hysterically. These were tricks I learned when I worked up in the Catskills.

Visiting Paris was a weekly event for me on my day off. I learned my way around very well and would meet my cousin, Leo Viola. He was a railroad battalion worker in the US Army. One time one of our planes accidently bombed his train yard where he was working. Luckily the pin on the bombs were still in and no one was killed. The bombardier on this plane was so tall that he accidentally pulled the release button and the bombs went right through the closed bomb bay doors.

.

Once on my return to camp from Paris, I was waiting for the train in Gare du Nord (one of six large terminus railway stations) and started talking to a girl named Paulette in French. We became friends and made a date for the next week. I still remember the beautiful town named Francoville. We enjoyed dancing to beautiful French music out in the open park up on a hill.

.

My interpreter friend wrote that he would meet me under the Arc di Triumph because he was not allowed to divulge where he lived. His name was Guerino Viola. Both my cousin, Leo Viola and Guerino came up to Pontois to see me.

My cousin Leo Viola came up to see me Gincour, Pontoise, France. He was stationed in Paris assigned to an American railroad battalion.

.

Our pay in France was always in American dollars. It would have a yellow stamp on each bill. When we left France at the end of the war we were advised to change any francs we had to US money because we would lose them if we didn’t. However that was not the truth.

.

The weather was getting colder and we built a shack near each plane. We put a stove inside and used the old oil from the planes to warm up the shack and our hands. Each man took a turn for a week and slept in the shack to guard the plane. It was dangerous. One night the fellow in the shack next to me had the oil run out on the floor. It caught fire and burned him badly. They took him back to England and we never saw him again.

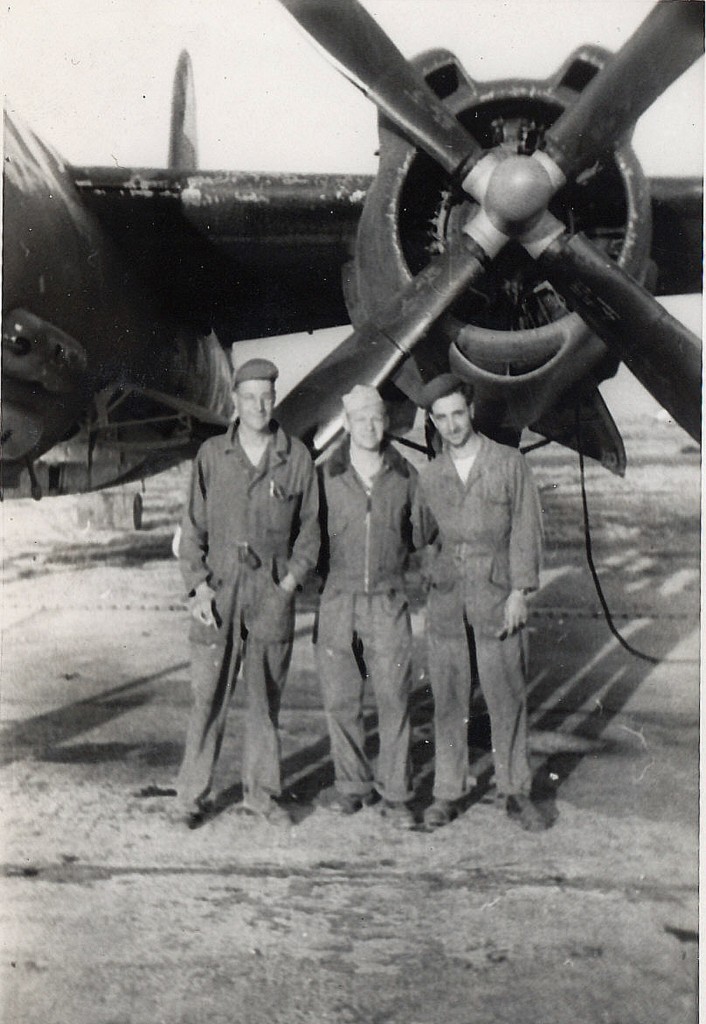

My crew chief, Ed Iverson on the left, can’t remember the other workers. The name of the plane is Ma’s Blasted Event

.

The snow started to come and we kept busy keeping the plane and the ground cleared. The plane had to be ready to fly at a moment’s notice. If the sky cleared, up went the planes. The time our troops were surrounded in Bastogne, Belgium, the sky was cloudy making it impossible to fly. But every day we tested the engines making sure they were ready in case there would be a clearing for a mission. The weather sometimes was so cold the plane would not start. We would change all the spark plugs and then it would start right up. Soon the sky cleared and the planes were able to fly missions and save our troops.

“My line crew. From left standing 3rd is Dick Reese, he’s the one that painted all the nose art on the planes.”

.

One day two B26s collided over the main road. I was in the back of the truck and did not know what was happening. The driver stopped and he realized he better run as the fifty caliber bullets were exploding from the heat of the crash. I was hanging off the back of the truck with one leg trying to get back in the truck when the driver started up again. It caused my leg to sustain an injury. It was a very scary moment.

On Sunday I went to church up on a hill in Janicouer, the small town outside of Pontoise. You could see the runway down below. All of a sudden I thought the walls of the church were going to cave in on me. Everyone ran outside and saw that the plane, fully loaded, had exploded on take off. An engine had gone out. There was black smoke everywhere. You could see the cloud of smoke rising up high.

One day a P47 was coming in for what should have been a normal landing on the same field. Suddenly, it came straight down to the ground. I saw the pilot with his arm over his head and then he crashed.

Once again we loaded all of our bicycles and equipment into the B26 and flew from France to Florennes, Belgium. On the way over we saw all the damage in the countryside. We landed on another metal runway as we found the airstrip full of bomb craters from our bombings. One day I was watching some men working to fill in the craters left by the bombs. I listened and was surprised to hear them talking my Tyrolian dialect. After awhile I answered them in their language. They were so surprised that a US soldier was one of them. Imagine my surprise when I realized one of them was Albino Endrizzi who lived in my town! On my days off I would ride my bicycle and visit another “cousin”! Albino soon left and went to Charlotte, Belgium with his family to work in the coal mines as there wasn’t any work in our town of Cavedago. I would visit them in Belgium and bring candy and cigarettes. Their entire street was all Tyrolians. I so enjoyed these visits.

One Tyrolian couple in Gerpinnes invited me to stay overnight at their home. They were alone as their son was working in a chateau. They loved having me and insisted I sleep in their nice, comfortable bed. Everyone treated me so well.

One day while riding my bike it broke. I found a mechanic in the small town of Gerpinnes who fixed it. When I asked him how much I owed him he asked for two cigarettes. I gave him a whole pack as I was so grateful.

Since I also spoke french, the Commanding Officer, Lucius Clay, told me to take fifteen guys and go take a roof off of a building that was too far from camp and put it on a building in the center of camp whose roof had been destroyed by a bomb. We made a nice, dry mess hall and had a big party when Clay’s father came for a visit. His father later became the General of the Occupational Army of Germany and Austria.

.

One day in the field in Florennes I met a man and asked if he knew anyone who would do my laundry. He said his wife would. They would always give me tea and cake when I visited. They had a fourteen year old daughter who reminded me of my younger sisters back in the states. I would take her to the fair and take her on rides. They were a very nice family.

From Florennes I would get a three day pass and go to Paris for R&R. We traveled all the way by truck on roads with craters and holes. We didn’t mind the bumps as long as we reached Paris. On each side of the road there were piles of ammuniition ready to be sent to Germany if needed. When the war ended, everything was brought back to the states. When it arrived in the US the long shoremen would load it on the train and then it went to storage, most probably to be used in the Korean War.

.

One day I asked Lucius Clay, my commanding officer, for a pass so I could go to Cavedago and see my maternal grandparents. He promised that when we went to Munich for the Army of Occupation he would fly me down to Milan. The war ended and they took a few of us young guys and sent us to a different outfit for the A26, a new plane, back in Pontoise, France. On the way to Pontoise we went to Rheems to wait for the new outfit to go to the Pacific. There I was assigned to guard duty to watch all the trucks, tanks and jeeps that were parked there. As far as my eyes could see, there were Army vehicles. Since the keys were in the vehicles I used the time there to learn how to drive, mostly on the jeeps. I never tried to drive a tank. When I returned to the states, I passed my road test on the first try!

My friends in my old outfit felt sorry for me as they thought I would be in the Air Force for two or three more years. I replied that I might get home before they would. As it turned out, the war ended and I was home six months before them as they went to Munich for occupation.

From Rheems we then went to Pontoise, to the same place we were before and we trained there for a couple of months on the A26. Since we had been there earlier in the war, we knew many of the people and reconnected with them. One night I was dancing with a woman I knew and another guy became jealous. He picked up a bottle and was going to hit me over the head with it. Fortunately one of my buddies stopped him.

.

Next we were sent to Marseilles, France to wait for the ship to go directly to the Pacific. There wasn’t any time to go visit my grandparents. The commanding officer advised me to stay with this new outfit as we would be the first to go home if the war ended.The guy in the office who always gave out the passes asked if I had any cousins in the Pacific. As the word paesan was not understood by non Italians, it was just easier to say that I wanted a pass to see my cousin. Indeed, I found many cousins to visit!

Fortunately the war ended. If the war had continued I would have gone straight to the Paciifc without any leave. Instead of going to the Pacific I returned to the United States on a small Norwegian freighter. The ride was rocky but I never got sick. We landed in Newport News, Virginia as the dock workers in New York were on strike. All the names of the soldiers coming in on the freighter were listed in the newspaper. My parents and sisters were so happy to see my name there. When we landed we were given a fantastic meal and treated royally

From Newport News we went by train to Fort Dix, New Jersey where we stayed for a week. There they gave us a thorough physical to make certain we were able to go home. We were celebrating the day we left on the train to New York. We kept drinking from a bottle at Penn Station. I must have passed out and when I woke I was in jail. The guard told me that I was in no condition to go home so they put me in a cell. I was supposed to be home by 8:30 p.m. The guard took me to where he found me and my duffel bag was still there. I checked my pocket and I still had my $700.00! I took the subway home. While I was in the service my family had moved from the apartment where I had lived with them to Jefferson Avenue. I didn’t realize that about twelve blocks away there was a Jefferson Street. I got off the train at Jefferson Street but soon learned I was in the wrong place. It was 4:30 a.m. when I arrived at the correct address and woke everyone up!

As I was one of the first soldiers home, I felt a little lost as none of my friends were home. After a couple of months I applied for a job working as a carpenter on Leonardo Pier, New Jersey. The man hiring me asked for my citizenship papers. When I replied I didn’t have them he said he could not hire me. When I explained that I fought in the war, he told me to go to Columbus Circle in Manhattan. My service in the Army Air Corp made me a citizen. I received the papers the same day and went to work on the pier for four months.The long shoremen would load the bombs that came back from Europe into the train boxcars. My job was to brace the bombs with 4 x 4s in the bulk head to hold the bombs in place.

.

Throughout my life, I held many different jobs but it was my time in the service that shaped my life. In September 2009 I went on the Honor Flight to Washington, D.C. with Marion. On the plane ride down I met my buddy, Frank Carrozza who served in my outfit.I hadn’t seen him since the war ended. Also I was surprised when my grandson, Ryan met us at the WWII Memorial. Seeing the monument filled me with pride.

In the fall of 2011, I attended my first reunion of my bomb group. Held in Minneapolis- St. Paul, my daughter, Marion and I drove from her home in Wisconsin. I was so excited to meet other guys from my group. Many had attended these reunions every year. There were eight in attendance from my outfit. Although it was my first, everyone welcomed me and we reminisced about the war. There were pilots, bombardiers, path finders, gunners and each had interesting stories. At dinner one evening, Ed Horn, a pilot, told his story of being a prisoner of war in a stalag. Marion met one guy, Casey Hasey, who lived just a mile from her home in Wisconsin.

Once back in Wisconsin I went to visit my friend, Joe Booz. I had met Joe years ago when Marion’s children were young and taking piano lessons from his wife. Joe and I were on the same air field in Bishop Stortford at exactly the same time, doing the exact same jobs but we were on opposite ends of the air base. We would talk non stop whenever I visited him.

In the fall of 2012, the reunion was held in Tucson, Arizona. Marion met me at the airport and we drove to the hotel. A tour of the Pima Air Base was the highlight. In the museum we saw memorabilia from our planes. At the end of the business meeting, the seven of us shared a bottle of brandy and drank to our fellow soldiers. Next year in Charleston, South Carolina we will meet again and drink the bottle of cognac that was purchased at the end of the war!