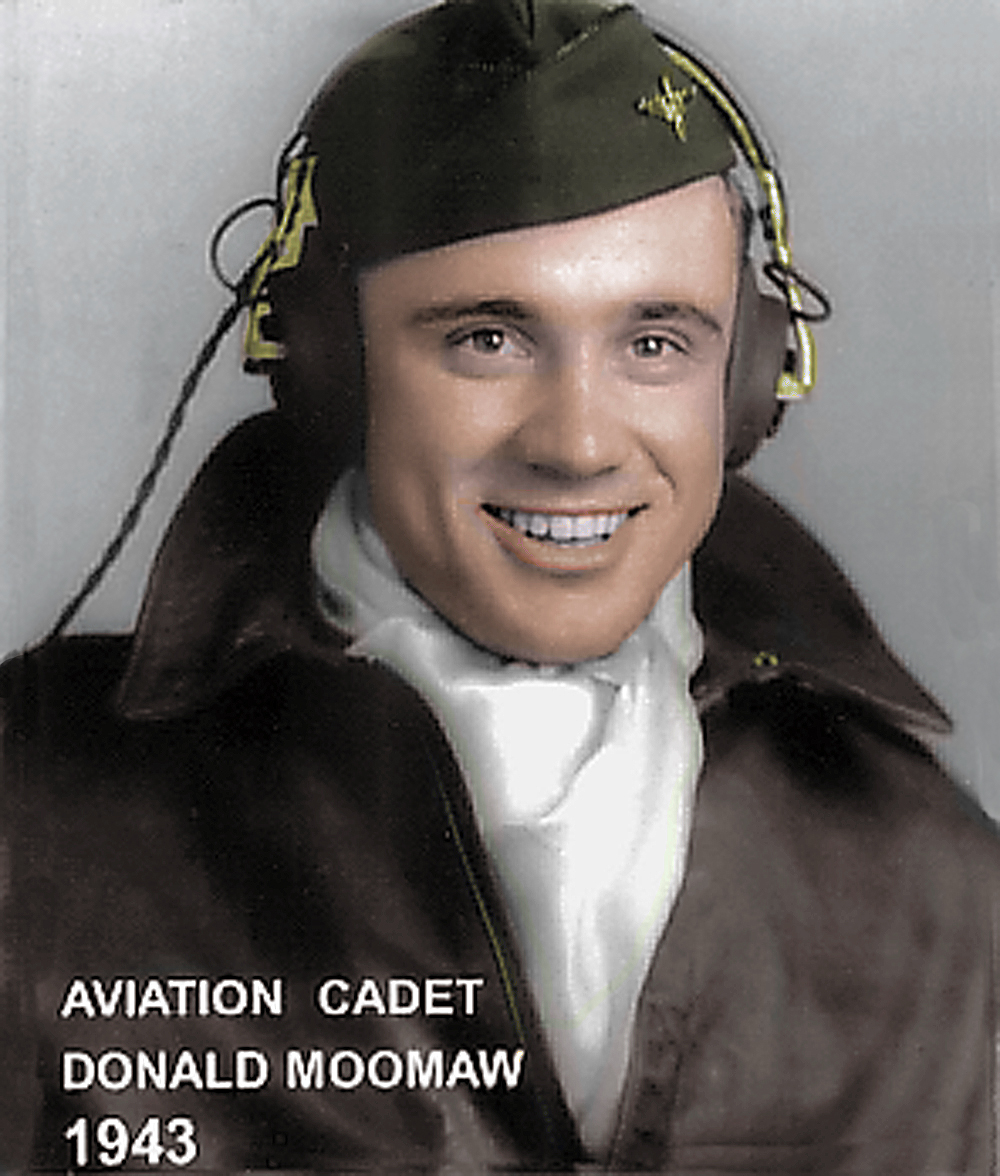

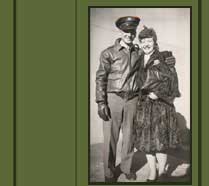

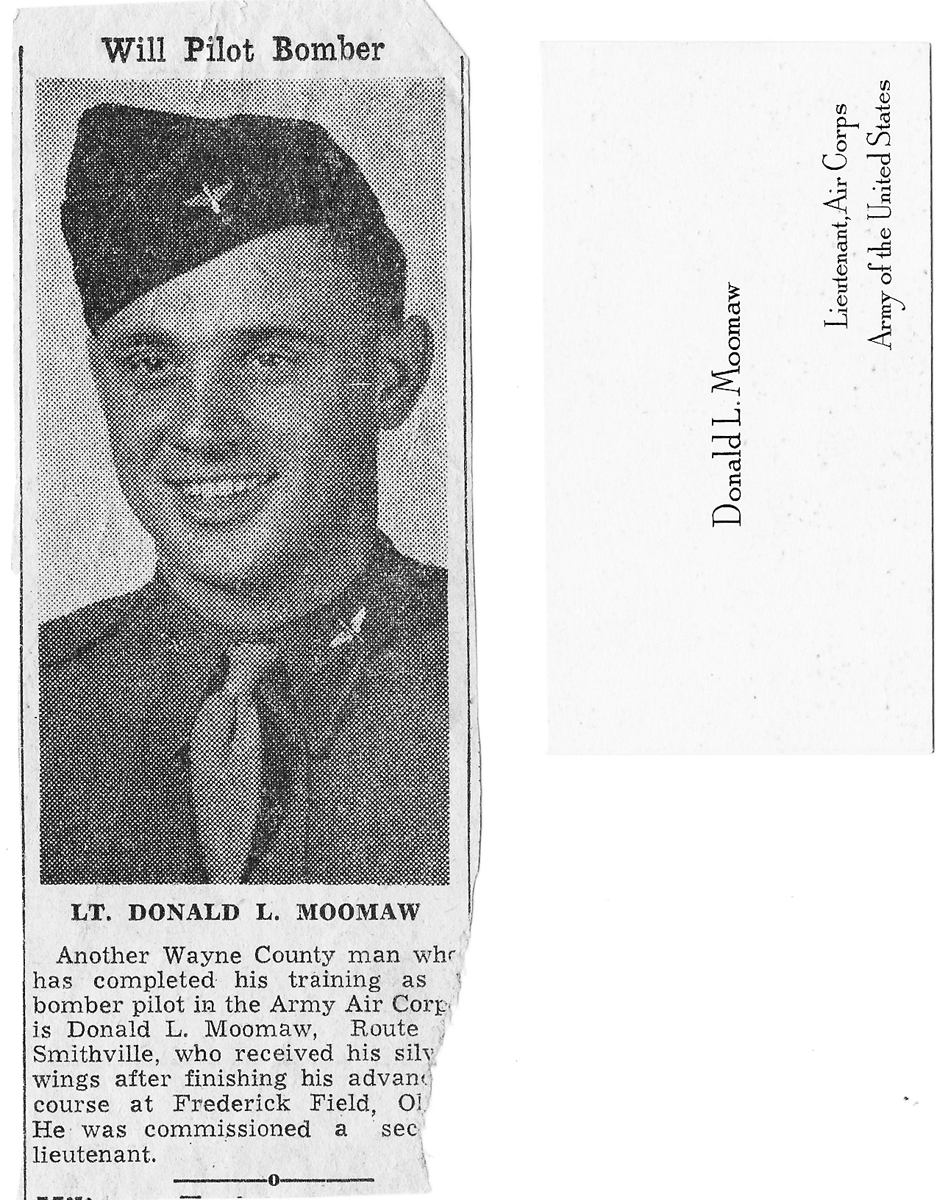

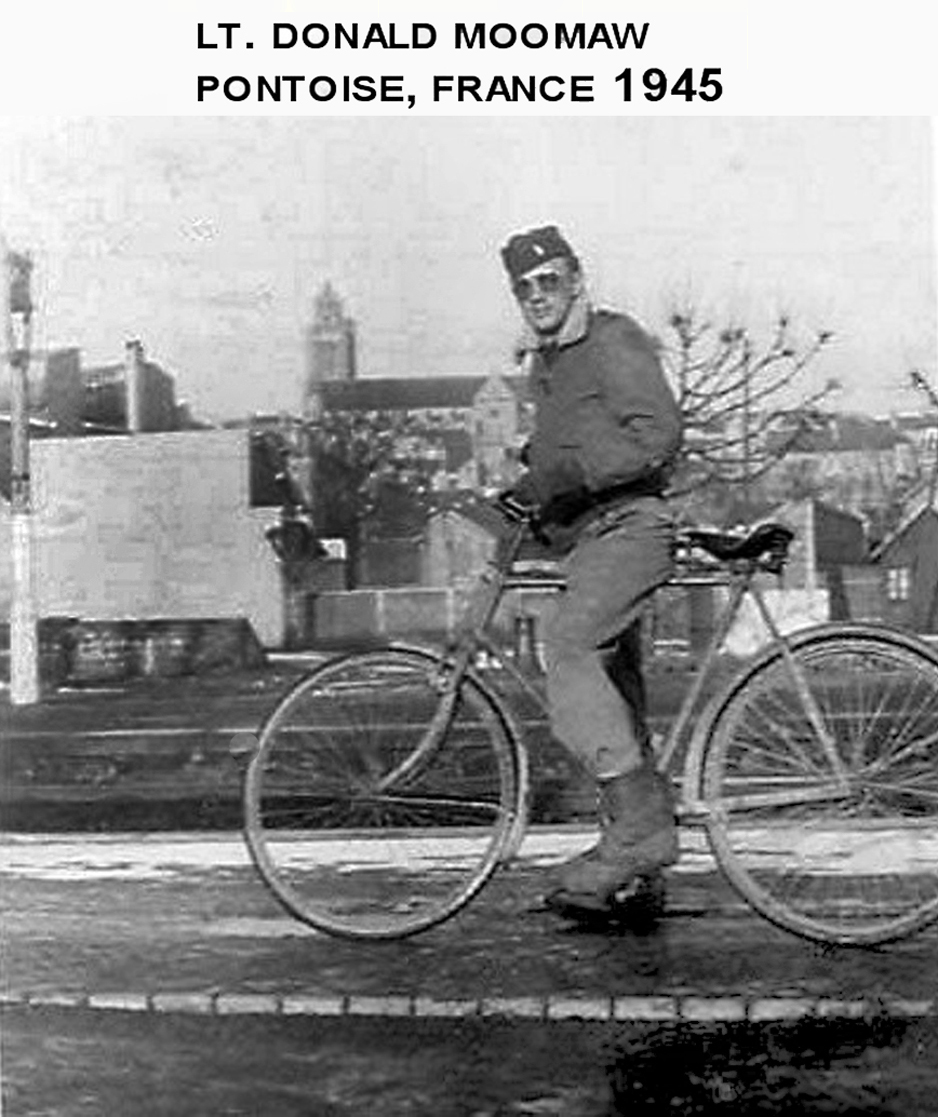

Lt. Donald Moomaw

*Note: Any photo can be enlarged by clicking it.

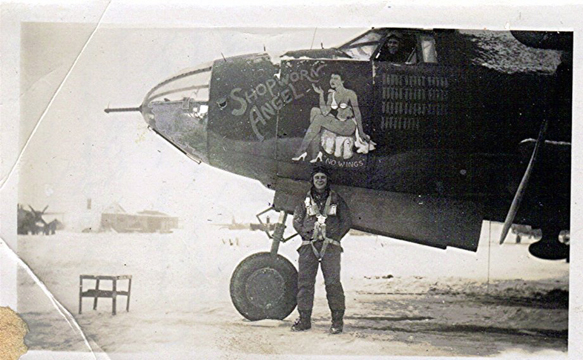

I was fortunate to first come in contact with Mr. Moomaw when I looked into a B-26 model he had posted for sale on e-bay. The plane was my father’s plane, the Shopworn Angel. I noticed that the plane model was painted in the distinctive manner of the Silver Streaks of the 495th. I suspected the owner was knowledgeable about the B26 and decided to contact him. I was amazed to learn of Lt. Moomaw’s eyewitness account of the last mission of the Shopworn Angel. I remain extremely grateful to Donald for the information. Also, our exchange of e-mails has reinforced what my father has told me about the 495th pilots being officers and gentlemen.

I was fortunate to first come in contact with Mr. Moomaw when I looked into a B-26 model he had posted for sale on e-bay. The plane was my father’s plane, the Shopworn Angel. I noticed that the plane model was painted in the distinctive manner of the Silver Streaks of the 495th. I suspected the owner was knowledgeable about the B26 and decided to contact him. I was amazed to learn of Lt. Moomaw’s eyewitness account of the last mission of the Shopworn Angel. I remain extremely grateful to Donald for the information. Also, our exchange of e-mails has reinforced what my father has told me about the 495th pilots being officers and gentlemen.

Links:

Don Moomaw describes the end of the Shopworn Angel

Moomaw and the demise of Tech. Sgt. Vanderlug

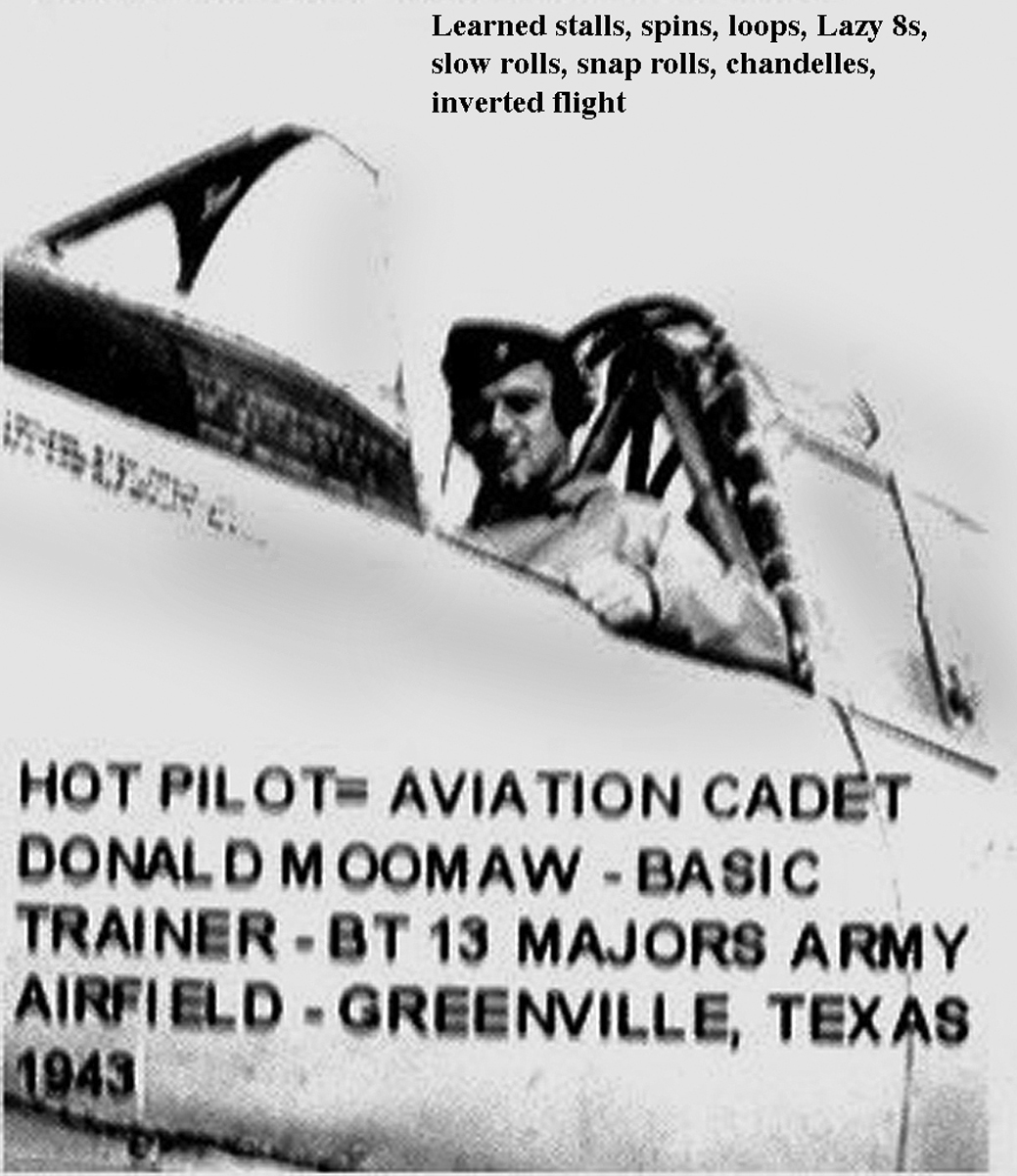

Here is an autobiographical piece on Mr. Moomaw’s military career;

Here is an autobiographical piece on Mr. Moomaw’s military career;

Below is an excerpt of the above limited to Moomaw’s experience in the ETO during wartime;

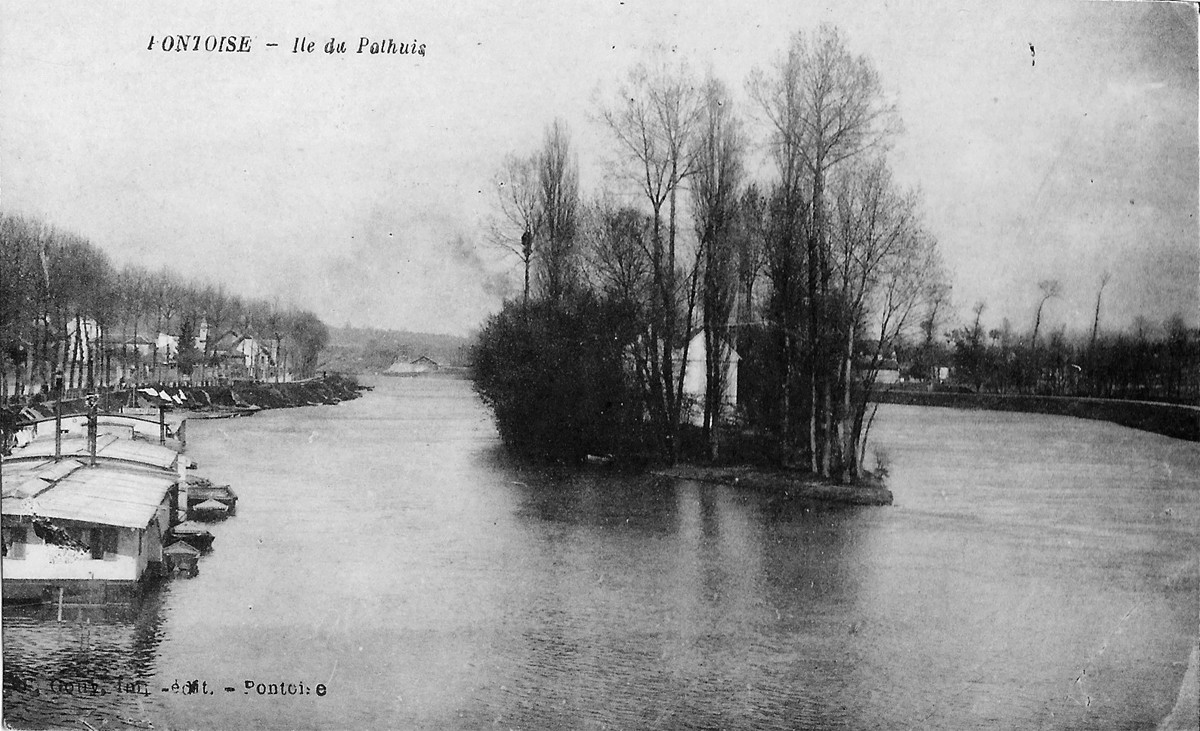

We were assigned, we eventually found out, we went to three 44th boundary. We were stationed near Pontois, France, The name Pontois meant the Ridge over the Oz River.

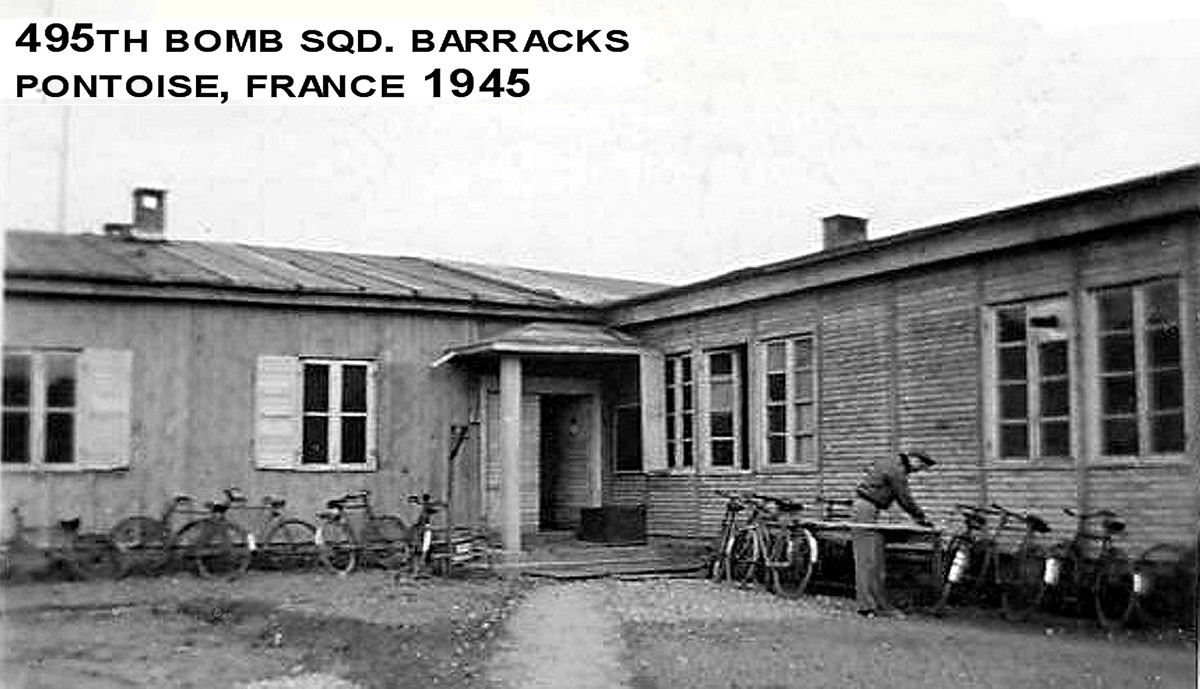

We were assigned, we eventually found out, we went to three 44th boundary. We were stationed near Pontois, France, The name Pontois meant the Ridge over the Oz River.  That ridge was blown up prior to the invasion. Anyway, we got there at night again. Always at night. You never got any place during the day. So they assigned us a room and bunks. There were no mattresses so they sent them out to get mattresses at what had been, I guess you’d call a whore house that the Germans had used. So they brought us mattresses and I was assigned an empty bunk. By the way, we were in an old French schoolhouse that the German Air Force had converted to a barracks for their use.

That ridge was blown up prior to the invasion. Anyway, we got there at night again. Always at night. You never got any place during the day. So they assigned us a room and bunks. There were no mattresses so they sent them out to get mattresses at what had been, I guess you’d call a whore house that the Germans had used. So they brought us mattresses and I was assigned an empty bunk. By the way, we were in an old French schoolhouse that the German Air Force had converted to a barracks for their use. That’s the only thing that was left of the air field. Everything else was destroyed except that and the runways. Now we were the only squadron in a building. The other three squadrons were in underground facilities that the Germans had used for housing. The airfield had one runway. Of course, it was a German fighter airfield and so there was only one way to take off and one way to land. The airfields in Europe had at least two runways so as the wind changed and so forth, they could take off into the wind. We didn’t have much choice. We had one way. Everything except our barracks was in tents. Mess hall, everything. At that airfield I knew of three places: the mess hall, where I slept, where the briefing tent was, and where the airplanes were. I never knew more. I didn’t need to know more. I didn’t know where squadron headquarters were, or group headquarters. probably in a tent somewhere. The schedule for flying was what they called a load list. About 4 o’clock in the afternoon they would post the crews that were going to fly the missions the next day. You were on that load list for three days. I f they flew three missions in a row, or four missions in that day, you flew them.

That’s the only thing that was left of the air field. Everything else was destroyed except that and the runways. Now we were the only squadron in a building. The other three squadrons were in underground facilities that the Germans had used for housing. The airfield had one runway. Of course, it was a German fighter airfield and so there was only one way to take off and one way to land. The airfields in Europe had at least two runways so as the wind changed and so forth, they could take off into the wind. We didn’t have much choice. We had one way. Everything except our barracks was in tents. Mess hall, everything. At that airfield I knew of three places: the mess hall, where I slept, where the briefing tent was, and where the airplanes were. I never knew more. I didn’t need to know more. I didn’t know where squadron headquarters were, or group headquarters. probably in a tent somewhere. The schedule for flying was what they called a load list. About 4 o’clock in the afternoon they would post the crews that were going to fly the missions the next day. You were on that load list for three days. I f they flew three missions in a row, or four missions in that day, you flew them.  Then you came off of the load list for one day. That didn’t mean you were free. It did, mainly, but if they needed extra crews or extra people you were scheduled the 4th or 5th or 6th day, whatever. Of course we were there in the winter and what determined how many missions you flew was the weather. Not the weather in France, but what the weather was in Germany, could we see the target? If you couldn’t see your target, there was no need of going. It didn’t matter if there was three feet of snow on the ground. When you were scheduled for a mission, it went to briefing, you got into your airplanes, started your engines, and got ready to take off. If the mission was cancelled, which it was many, many times on account of the weather, they would shoot up a red flare from the control tower. But that didn’t change things. If you were scheduled to the mission, you went to a briefing, you got in your airplane, you started it up, ready to taxi out.

Then you came off of the load list for one day. That didn’t mean you were free. It did, mainly, but if they needed extra crews or extra people you were scheduled the 4th or 5th or 6th day, whatever. Of course we were there in the winter and what determined how many missions you flew was the weather. Not the weather in France, but what the weather was in Germany, could we see the target? If you couldn’t see your target, there was no need of going. It didn’t matter if there was three feet of snow on the ground. When you were scheduled for a mission, it went to briefing, you got into your airplanes, started your engines, and got ready to take off. If the mission was cancelled, which it was many, many times on account of the weather, they would shoot up a red flare from the control tower. But that didn’t change things. If you were scheduled to the mission, you went to a briefing, you got in your airplane, you started it up, ready to taxi out. If you were going to go on the mission, then a green flare would go up. All this was done on a scheduled time. You checked your airplane, got into the airplane. That flare, they would send it and everyone started their engines. About five minutes later another flare would go up and you started taxiing. Everyone knew where they were positioned in the group and so you would join the parade where you were supposed to be. You would taxi in a straight line out to the takeoff point. At that time you waited for another green flare. The first plane off, the lead plane, when the flare went up he was out on the runway and released his brakes and his engine and started rolling. Every 20 seconds another plane, as quick as that plane started rolling, the next plane rolled out to the take off point, revved his engine up full speed, and the brakes, and that old plane would just bounce there with those twin engines at full power. We would take off every 20 seconds. We would goout on therunway with our engines full blast, 0ur engines were set to 2800 rpm and 52 inches of mercury, if we could we could get 2850 rpm’s and 53 inches of mercury we got it. And the copilot would time it. And when 20 seconds was up, he would motion the pilot and release the brakes and down the runway we’d go. Soat that time, there was one plane just taking off, one plane just about half way down way, and another plane just starting to roll. So even at every 20 seconds, it took us, depending on how many planes, 12 to 15 minutes to get in the air. Once we got in the air, we knew the heading we were supposed to take, and it was a clear day, of course you would just take off and go climb to your altitude and get into formation.

If you were going to go on the mission, then a green flare would go up. All this was done on a scheduled time. You checked your airplane, got into the airplane. That flare, they would send it and everyone started their engines. About five minutes later another flare would go up and you started taxiing. Everyone knew where they were positioned in the group and so you would join the parade where you were supposed to be. You would taxi in a straight line out to the takeoff point. At that time you waited for another green flare. The first plane off, the lead plane, when the flare went up he was out on the runway and released his brakes and his engine and started rolling. Every 20 seconds another plane, as quick as that plane started rolling, the next plane rolled out to the take off point, revved his engine up full speed, and the brakes, and that old plane would just bounce there with those twin engines at full power. We would take off every 20 seconds. We would goout on therunway with our engines full blast, 0ur engines were set to 2800 rpm and 52 inches of mercury, if we could we could get 2850 rpm’s and 53 inches of mercury we got it. And the copilot would time it. And when 20 seconds was up, he would motion the pilot and release the brakes and down the runway we’d go. Soat that time, there was one plane just taking off, one plane just about half way down way, and another plane just starting to roll. So even at every 20 seconds, it took us, depending on how many planes, 12 to 15 minutes to get in the air. Once we got in the air, we knew the heading we were supposed to take, and it was a clear day, of course you would just take off and go climb to your altitude and get into formation. But if it was cloudy and you had to climb through the clouds, and sometimes you would climb through 10,000–12,000 feet through clouds that you couldn’t see your wing tips and you had a plane ahead of you 20 seconds and a plane behind you 20 seconds, all climbing at the same compass heading and the same air speed. We climbed at 180 miles per hour, climbing 300 feet per minute. And we did break through those clouds, even though we were all heading on the same compass heading at the same air speed, planes were all over that sky and the compasses weren’t that close and the air speed indicators weren’t that close. So what the lead plane would do is make a large circle and we would cut into it. We would spot the lead plane and then we would get into our spot. It seemed to work. I don’t know why, but we would get in our spot and take off for Germany. We flew 12,000 to 14,000 feet. All the other Air Force fighters and the heavy bombers had oxygen and oxygen masks and so forth. We didn’t. So we were flying at 12,000 and 14,000 feet without oxygen. I often wonder, I would always become so terribly tired and I didn’t realize it until after the war, we were just oxygen starved. Well anyway, when we got over Germany, what we called the bomb line, the bomb line was where you were entering enemy territory. Whether it was France, Belgium, or Germany, when you crossed the bomb line then you got credit for a mission, whether you dropped your bombs or not. Very few times, I think only one time we did not drop bombs. We knew when we would hit flack. This is antiaircraft fire. There were three flak

But if it was cloudy and you had to climb through the clouds, and sometimes you would climb through 10,000–12,000 feet through clouds that you couldn’t see your wing tips and you had a plane ahead of you 20 seconds and a plane behind you 20 seconds, all climbing at the same compass heading and the same air speed. We climbed at 180 miles per hour, climbing 300 feet per minute. And we did break through those clouds, even though we were all heading on the same compass heading at the same air speed, planes were all over that sky and the compasses weren’t that close and the air speed indicators weren’t that close. So what the lead plane would do is make a large circle and we would cut into it. We would spot the lead plane and then we would get into our spot. It seemed to work. I don’t know why, but we would get in our spot and take off for Germany. We flew 12,000 to 14,000 feet. All the other Air Force fighters and the heavy bombers had oxygen and oxygen masks and so forth. We didn’t. So we were flying at 12,000 and 14,000 feet without oxygen. I often wonder, I would always become so terribly tired and I didn’t realize it until after the war, we were just oxygen starved. Well anyway, when we got over Germany, what we called the bomb line, the bomb line was where you were entering enemy territory. Whether it was France, Belgium, or Germany, when you crossed the bomb line then you got credit for a mission, whether you dropped your bombs or not. Very few times, I think only one time we did not drop bombs. We knew when we would hit flack. This is antiaircraft fire. There were three flak Flack was an 88mm shell. Now what 88 mm is, whether it’s 2 inches or 3 inches or 4 inches, I don’t know. But when that would explode, the pieces would be from the size of your thumbnail to the size of your hand, however the thing broke, and it was flying through like a hailstorm, really. Now, a piece the size of a thumbnail, if it hit the right place, it would bring you down. Or if it hit you at the right place it would bring you down, kill you. But anyway, how can I say it, once it came up, you were so busy it didn’t bother you. Your mind couldn’t, my mind couldn’t take it all in. So it was just there. You could see the red bursts. Not all the time, but when it was close, accurate, and heavy you could see the red bursts. You could hear the pinging. You could smell the acid smoke. You could feel it at times tearing through your airplane. You could hear it. You could feel it. You were just there. There was nothing you could do about it. You were trained to fly formation. Whatever your leader did, you did. There were no questions asked. You just did it. You dropped your bombs about 2 miles from the target and the forward motion carried the bomb into the target. We weren’t as accurate as they would have liked, but we did hit our targets. Now when we carried 2000 pound bombs, when they hit and exploded they just tossed your airplane in the air. Not toss it, but lift it up. When we pulled off the target, as quick as our bombs would have dropped, we would always make a steep diving turn either to the

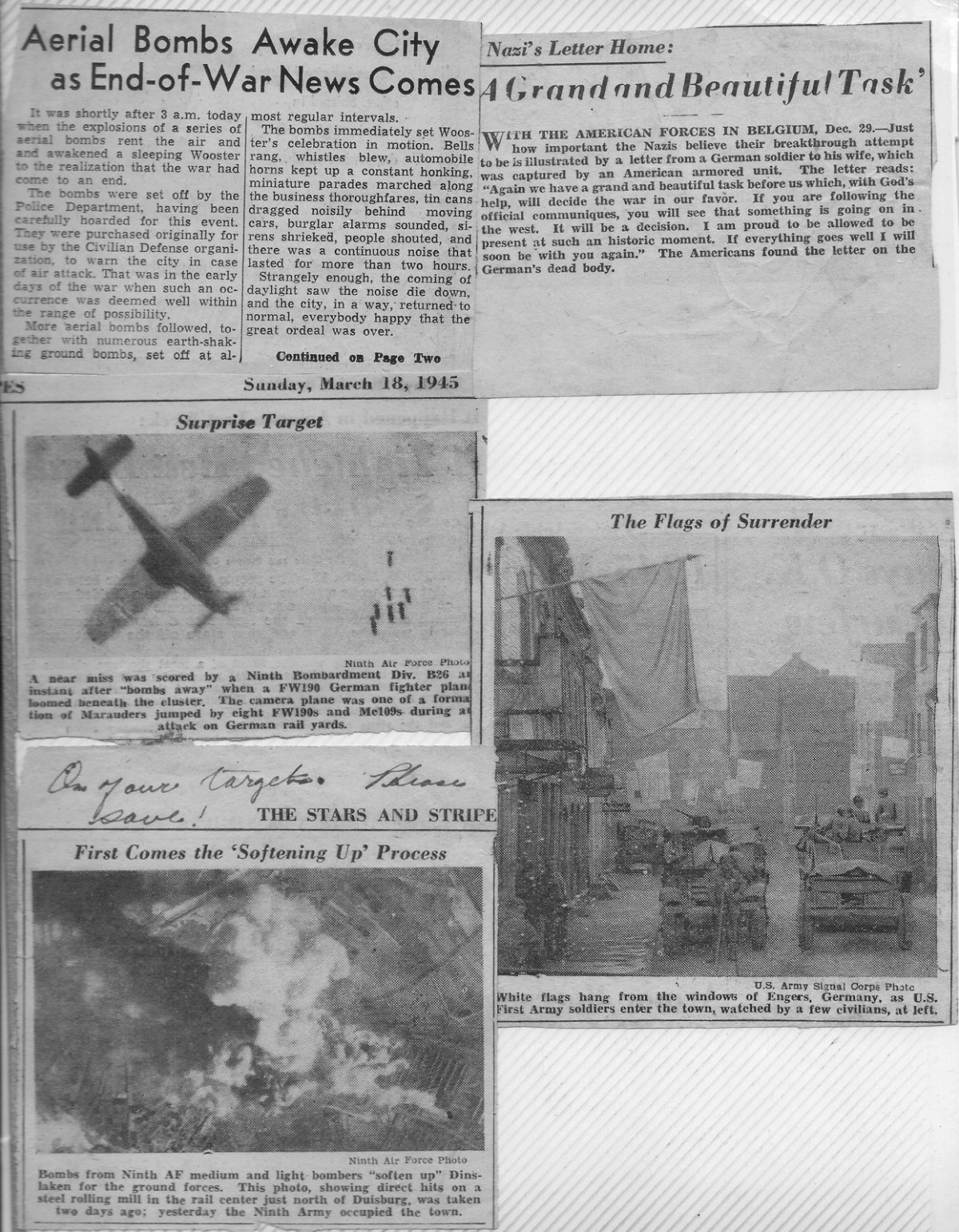

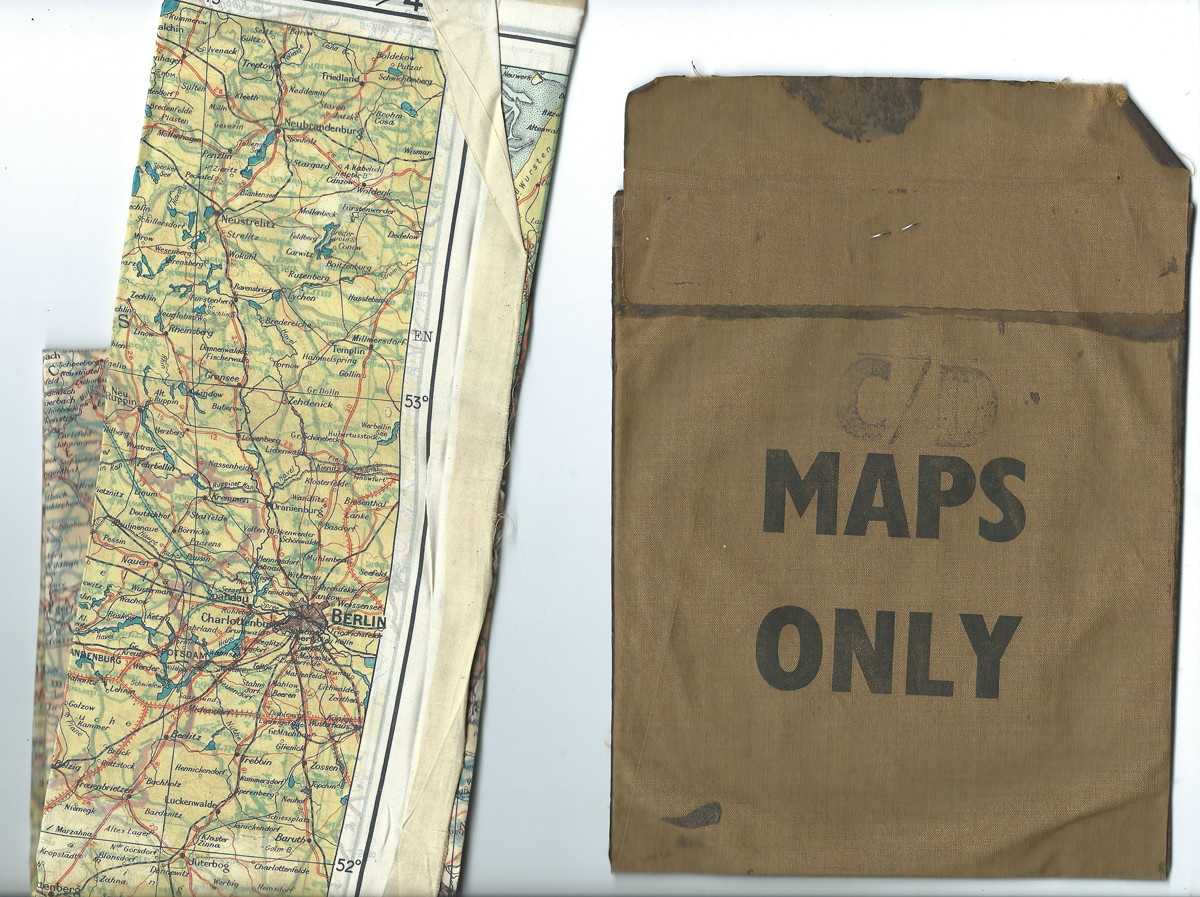

Flack was an 88mm shell. Now what 88 mm is, whether it’s 2 inches or 3 inches or 4 inches, I don’t know. But when that would explode, the pieces would be from the size of your thumbnail to the size of your hand, however the thing broke, and it was flying through like a hailstorm, really. Now, a piece the size of a thumbnail, if it hit the right place, it would bring you down. Or if it hit you at the right place it would bring you down, kill you. But anyway, how can I say it, once it came up, you were so busy it didn’t bother you. Your mind couldn’t, my mind couldn’t take it all in. So it was just there. You could see the red bursts. Not all the time, but when it was close, accurate, and heavy you could see the red bursts. You could hear the pinging. You could smell the acid smoke. You could feel it at times tearing through your airplane. You could hear it. You could feel it. You were just there. There was nothing you could do about it. You were trained to fly formation. Whatever your leader did, you did. There were no questions asked. You just did it. You dropped your bombs about 2 miles from the target and the forward motion carried the bomb into the target. We weren’t as accurate as they would have liked, but we did hit our targets. Now when we carried 2000 pound bombs, when they hit and exploded they just tossed your airplane in the air. Not toss it, but lift it up. When we pulled off the target, as quick as our bombs would have dropped, we would always make a steep diving turn either to the Anyway, we got on the bomb run and a pink or a red burst came up, I thought that was unusual. And then a short time later, just enough time that they had all been zeroing in on us, and the flack, you’ve heard the expression “the flak was so thick you could walk on it.” It was. Our flight never reached the target. As I said, you followed your leader. Somewhere along the line he made a steep diving turn to the left. I assumed they were turning off, that we had gotten rid of our bombs. I things were so…so… you couldn’t think. Naturally, you followed. But he was shot out of control, he hadn’t dropped his bomb. The way we dropped bombs, when the lead plane dropped the bombs, the lead plane had the bombardier in it, and our bombardier would just throw]a switch and release our bombs. Well previous to that, too, I had just caught a glimpse of the #3 position in peripheral vision his right engine was on fire and making a gradual turn out of the formation. That’s the last that plane was ever heard of, the crew. But anyway, we didn’t get rid of our bombs. We had heavier damage than we knew, when we got out and got flying home, the steering mechanism, I mean the controls, were sort of not right, it just wasn’t right. So we pulled way left of the formation so that if something did happen to us, we didn’t take somebody else with us, I mean like crashing into another one. When the planes were inspected afterwards, ¾ of that control column was blown away. Cut off or whatever by flak. Also, we didn’t know this damage. We had a destroyed fuel line. That flack had cut it had sealed it. Now, on a return oil line that wasn’t bad except that you would lose oil. But by sealing it didn’t happen. Had it been on a feed line, we would have lost our engine and so forth. Anyway, had we lost an engine with the control column the way it was, that would have been the end. But anyway, I’ve got the oil line here, that piece that the ground crew cut out, and it shows how it was sealed and we lost oil, but no that great amount. Each engine carried 50 gallons of oil so it’s a pretty good supply. Also, I have a small piece of flak that shows what flak is. We were so shot up on that mission that the group was grounded the next day to get the airplanes back in shape, get extra crews, and get extra aircraft . That’s the way it was. So we kept on going and then we had another mission. I guess there were two of them like that. I’m sorry I missed the second one. You never knew what the missions were, what you didn’t fly on them. You didn’t talk about those things. You didn’t even talk about a mission after it was over. It was done. What happened, happened. Anyway, we were scheduled to go into Germany. This was in February. Only the big towns with the big targets were hit in Germany. This time they wanted to show the little towns and so forth that there was a war on and sort of get the German people to understand what was happening and maybe influence the government and their soldiers to call it quits. So we went into Germany on the regular formation. We went beyond our targets and we split into three plane elements, which rather than 36 or 42 hitting the target, only three hit it. I don’t know what our target was, what town. So we went beyond our targets and came down to 6000 feet and whatever town it was, we bombed, circled around, and came in and strafed it. And as we were going in strafing, just before we started strafing, I saw a parachute coming down, of course with a pilot in it, and it had to be one of the P51 escort pilots. But my God, coming down into….. Of course, I don’t know how far away he was from the target at the time, maybe he didn’t land close to it, but I thought my God, what chance does he have with what we’re doing. Anyway, as were coming in strafing, I assume 40 mm guns at this altitude, and each 5th shell, whether it was a machine gun or 40mm was a tracer. And those tracers were coming up as thick as you could see. But they couldn’t keep up with us. They were all flowing in under us. In other words, they couldn’t lead us enough. Had we been maybe 1000 feet back, the plane and the ammo might have been at the same altitude. But they couldn’t lead us enough that it was just flowing in under us. After we did our strafing and pulled off, of course I don’t know what speed we were going, probably 350 to 400 mph and pulling that B26 up with a half load of gas and no bombs, we went up like a fighter. We really gained altitude. I read after the war, I suppose 50 years after the war, that there were two missions that way. I don’t know whether we were the first of the second.

Anyway, we got on the bomb run and a pink or a red burst came up, I thought that was unusual. And then a short time later, just enough time that they had all been zeroing in on us, and the flack, you’ve heard the expression “the flak was so thick you could walk on it.” It was. Our flight never reached the target. As I said, you followed your leader. Somewhere along the line he made a steep diving turn to the left. I assumed they were turning off, that we had gotten rid of our bombs. I things were so…so… you couldn’t think. Naturally, you followed. But he was shot out of control, he hadn’t dropped his bomb. The way we dropped bombs, when the lead plane dropped the bombs, the lead plane had the bombardier in it, and our bombardier would just throw]a switch and release our bombs. Well previous to that, too, I had just caught a glimpse of the #3 position in peripheral vision his right engine was on fire and making a gradual turn out of the formation. That’s the last that plane was ever heard of, the crew. But anyway, we didn’t get rid of our bombs. We had heavier damage than we knew, when we got out and got flying home, the steering mechanism, I mean the controls, were sort of not right, it just wasn’t right. So we pulled way left of the formation so that if something did happen to us, we didn’t take somebody else with us, I mean like crashing into another one. When the planes were inspected afterwards, ¾ of that control column was blown away. Cut off or whatever by flak. Also, we didn’t know this damage. We had a destroyed fuel line. That flack had cut it had sealed it. Now, on a return oil line that wasn’t bad except that you would lose oil. But by sealing it didn’t happen. Had it been on a feed line, we would have lost our engine and so forth. Anyway, had we lost an engine with the control column the way it was, that would have been the end. But anyway, I’ve got the oil line here, that piece that the ground crew cut out, and it shows how it was sealed and we lost oil, but no that great amount. Each engine carried 50 gallons of oil so it’s a pretty good supply. Also, I have a small piece of flak that shows what flak is. We were so shot up on that mission that the group was grounded the next day to get the airplanes back in shape, get extra crews, and get extra aircraft . That’s the way it was. So we kept on going and then we had another mission. I guess there were two of them like that. I’m sorry I missed the second one. You never knew what the missions were, what you didn’t fly on them. You didn’t talk about those things. You didn’t even talk about a mission after it was over. It was done. What happened, happened. Anyway, we were scheduled to go into Germany. This was in February. Only the big towns with the big targets were hit in Germany. This time they wanted to show the little towns and so forth that there was a war on and sort of get the German people to understand what was happening and maybe influence the government and their soldiers to call it quits. So we went into Germany on the regular formation. We went beyond our targets and we split into three plane elements, which rather than 36 or 42 hitting the target, only three hit it. I don’t know what our target was, what town. So we went beyond our targets and came down to 6000 feet and whatever town it was, we bombed, circled around, and came in and strafed it. And as we were going in strafing, just before we started strafing, I saw a parachute coming down, of course with a pilot in it, and it had to be one of the P51 escort pilots. But my God, coming down into….. Of course, I don’t know how far away he was from the target at the time, maybe he didn’t land close to it, but I thought my God, what chance does he have with what we’re doing. Anyway, as were coming in strafing, I assume 40 mm guns at this altitude, and each 5th shell, whether it was a machine gun or 40mm was a tracer. And those tracers were coming up as thick as you could see. But they couldn’t keep up with us. They were all flowing in under us. In other words, they couldn’t lead us enough. Had we been maybe 1000 feet back, the plane and the ammo might have been at the same altitude. But they couldn’t lead us enough that it was just flowing in under us. After we did our strafing and pulled off, of course I don’t know what speed we were going, probably 350 to 400 mph and pulling that B26 up with a half load of gas and no bombs, we went up like a fighter. We really gained altitude. I read after the war, I suppose 50 years after the war, that there were two missions that way. I don’t know whether we were the first of the second.

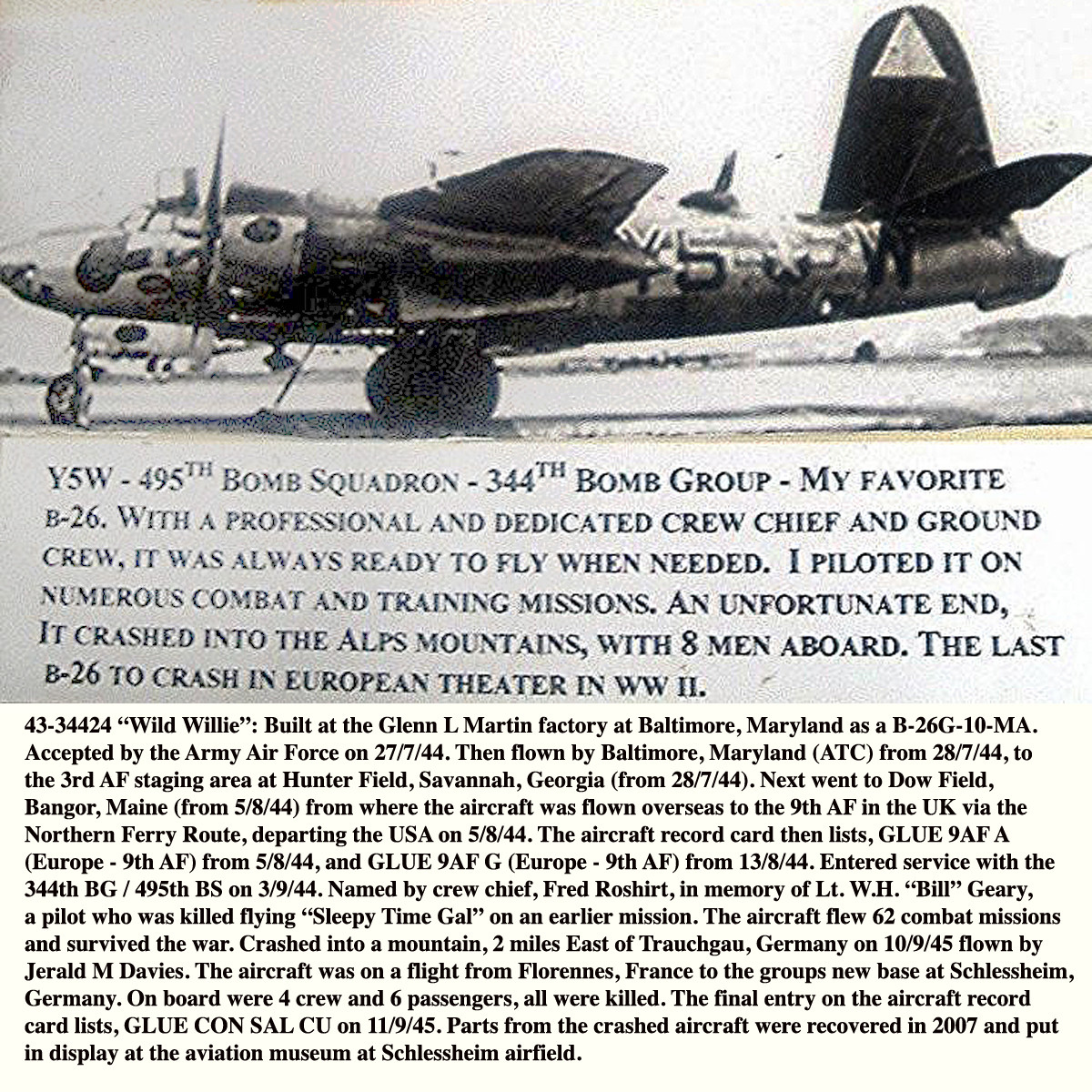

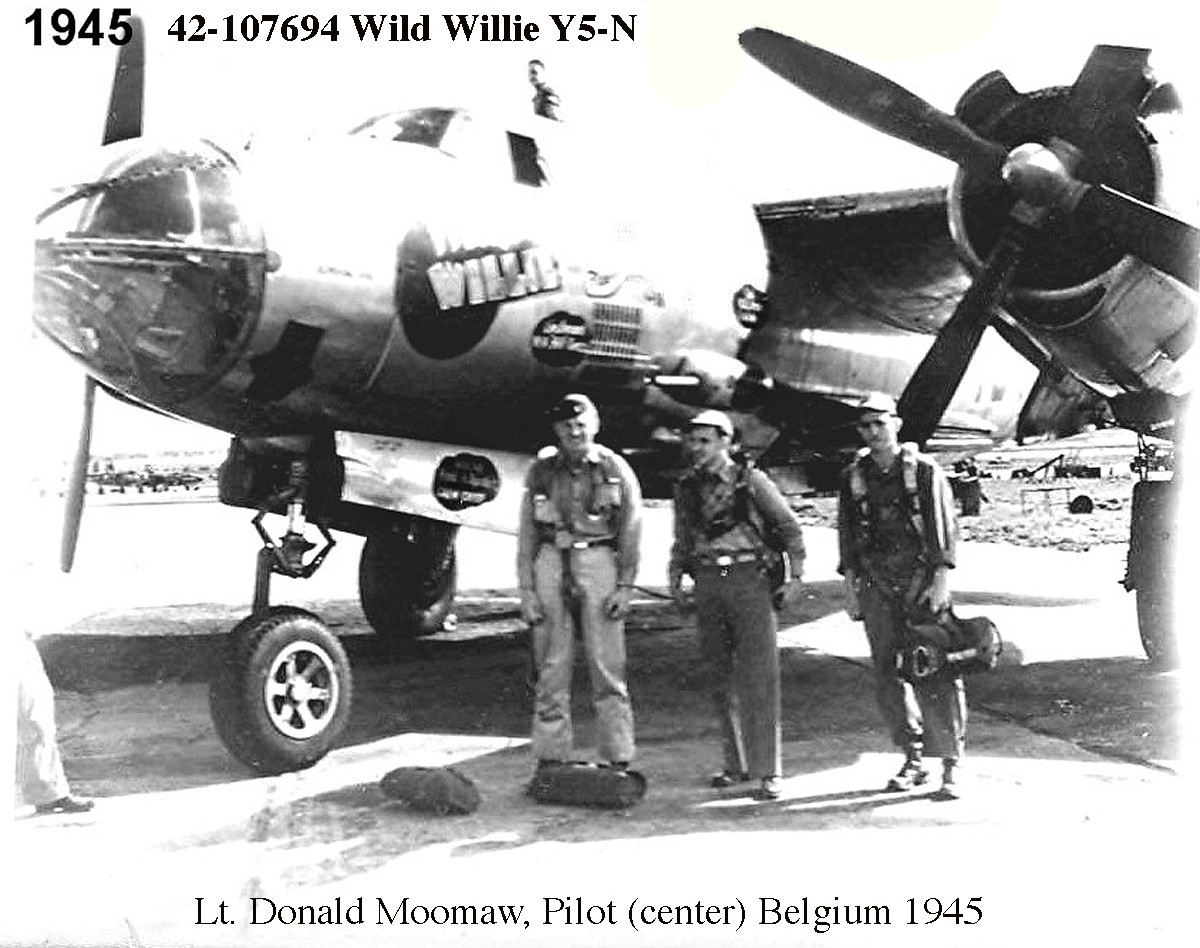

I don’t remember the trip down. I just remember arriving. I’m sure you people have heard this story previously, but the first thing I heard when I got there were two German war prisoners talking and one of them said, “Comens zee here.” Well, of course I knew what “Comens zee here” meant, it meant come here. Well, I said, I have no problems. That was the last German I understood the whole time I was there. On a trip going down, Y5W aircraft, Wild Willy, which I flew a number of times and I have pictures here scattered all over the place, got lost going on a trip down to Slieshiem and flew into the Alps Mountain, killing all eight people on board.

I don’t remember the trip down. I just remember arriving. I’m sure you people have heard this story previously, but the first thing I heard when I got there were two German war prisoners talking and one of them said, “Comens zee here.” Well, of course I knew what “Comens zee here” meant, it meant come here. Well, I said, I have no problems. That was the last German I understood the whole time I was there. On a trip going down, Y5W aircraft, Wild Willy, which I flew a number of times and I have pictures here scattered all over the place, got lost going on a trip down to Slieshiem and flew into the Alps Mountain, killing all eight people on board. One of the eight was the crew chief of Y5W, and when the war ended he had enough points to go home. But they got him to volunteer to stay to maintain the aircraft until they didn’t need him anymore. Well, he stayed, and his master, but didn’t go home. That’s the way life goes.

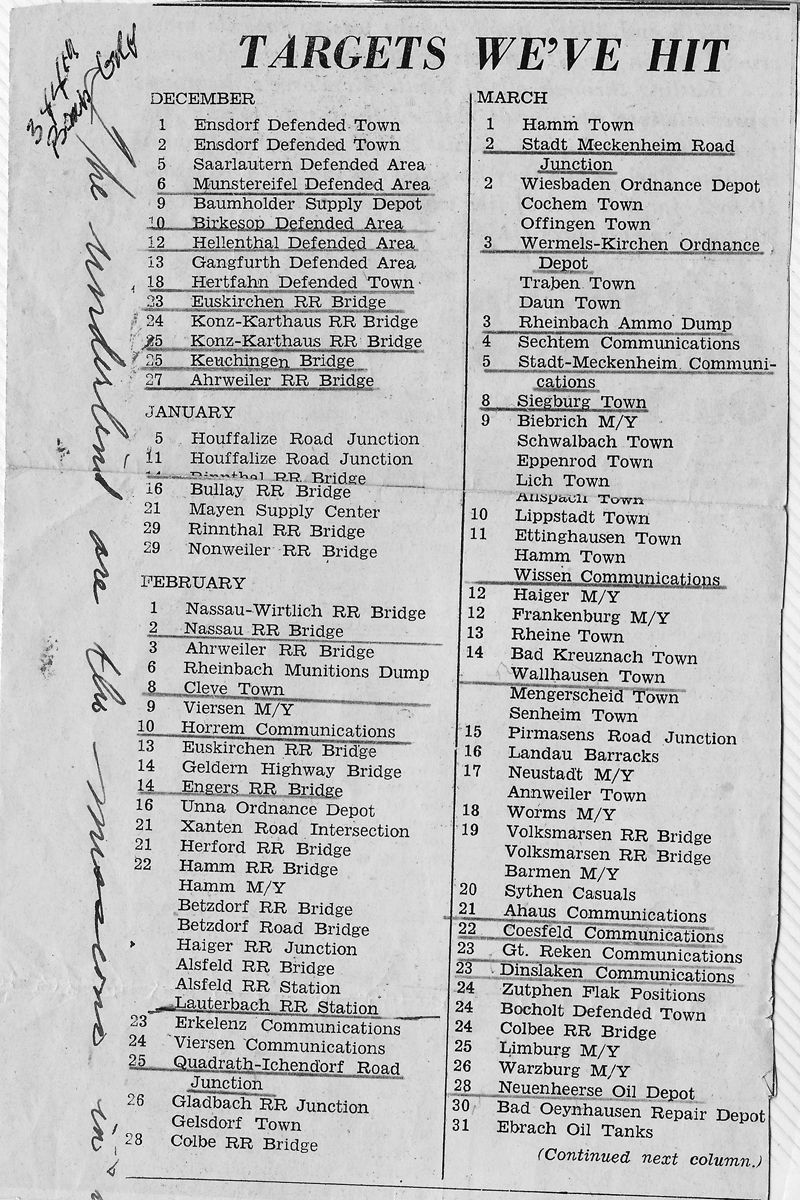

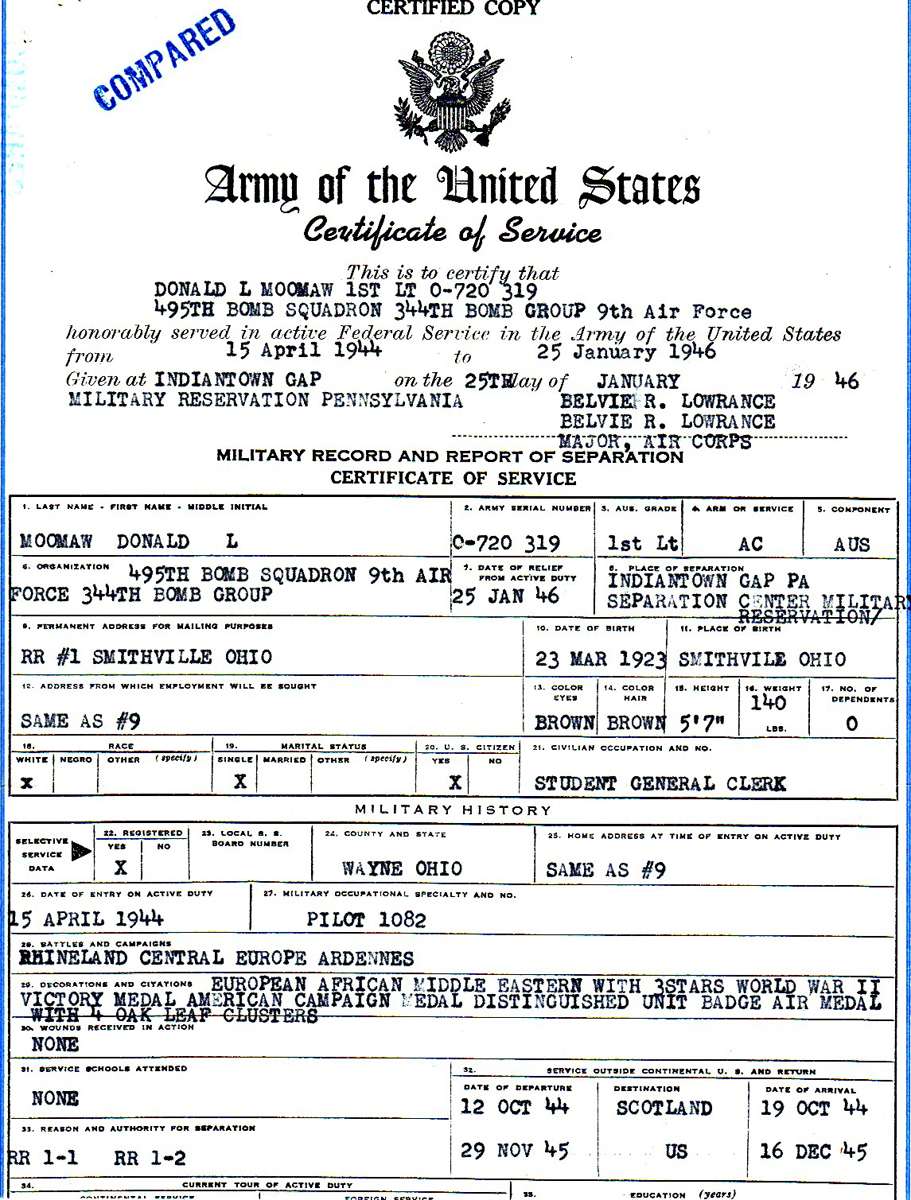

One of the eight was the crew chief of Y5W, and when the war ended he had enough points to go home. But they got him to volunteer to stay to maintain the aircraft until they didn’t need him anymore. Well, he stayed, and his master, but didn’t go home. That’s the way life goes.Here are the documents that certify the dates of his combat flights;

Don Moomaw: “We had a Catholic Chaplain in our group. Regardless of the weather or conditions,he was at the take off point waving goodbye and, I suppose, wishing a safe trip, and possibly the last rites. I thought this was so great as it was the last display or bit of kindness for a lot of men were to receive. On occasions some had less than a minute to live, if you lost an engine on take off, it was all over. Others had five minutes to several hours. I wish I could remember his name and contact him, but I am certain he has passed on by now.”

“Christmas 1943, Brother Jr. was stationed, at Camp Crowder, Missouri.I was in Greenville, Texas. We spent Christmas day together at a military post in Oklahoma. We had a place for sleep and food. We played some ping-pong, and talked. I am sure the folks were happy that we could get together. Transportation and time together, have no recollection.”

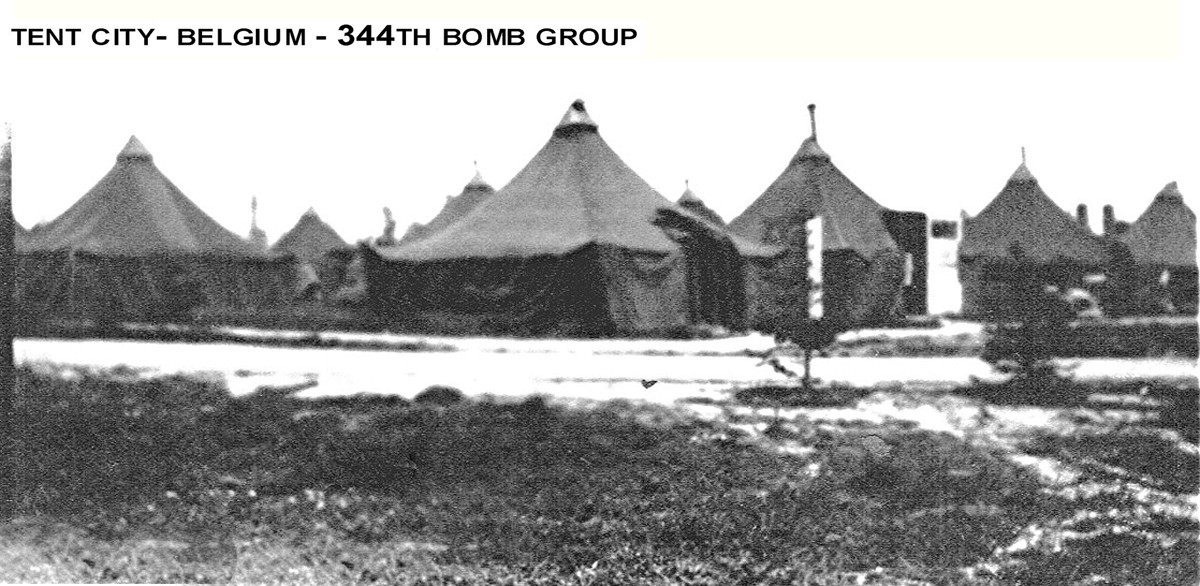

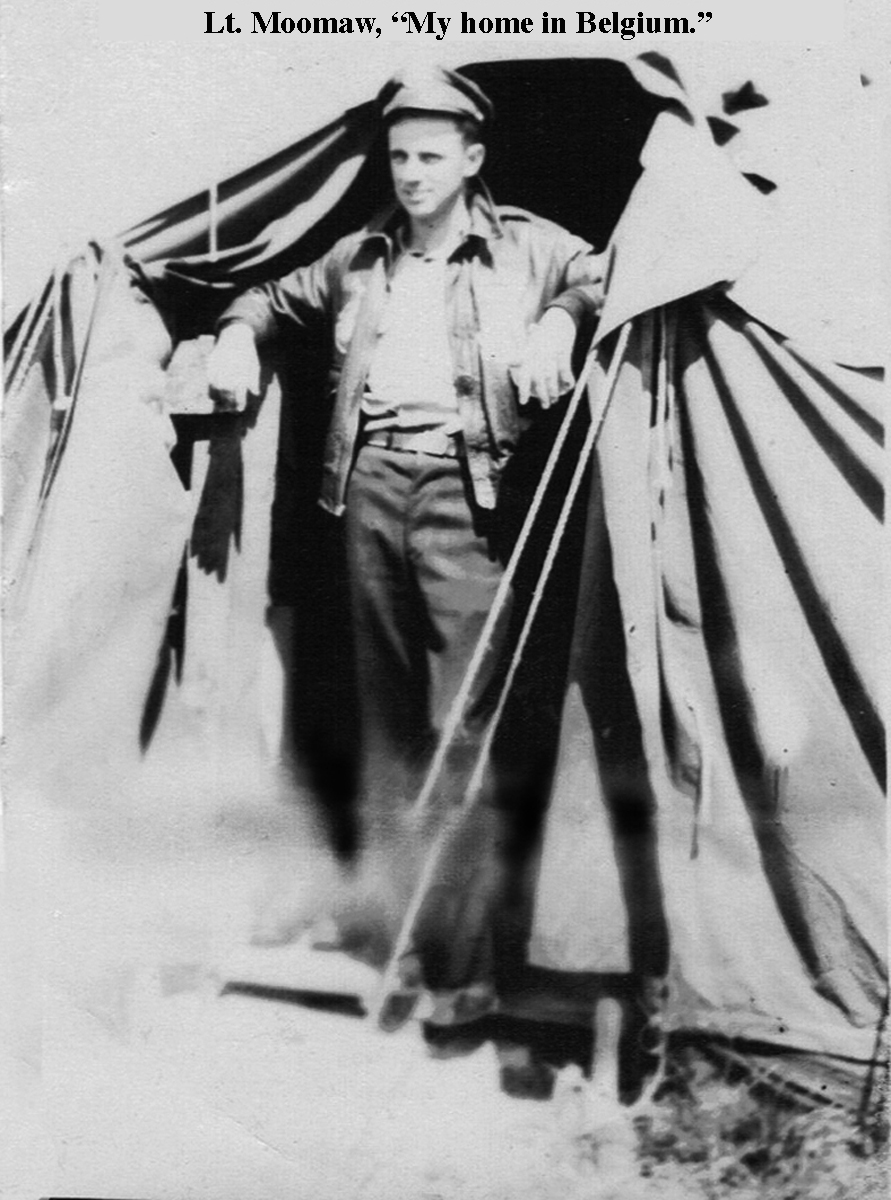

“In France, I mention we lived in an converted school house, I presume the room was originally meant for one person, there were four of us. It was heated by a small stamped out steel stove, about the size of a five gallon can. Every place I was stationed, except Primary Flight School, was heated in this manner. In France, if you wanted heat, you cut wood. Logs were brought into the area, axes and saws were available, we cut wood. In Belgium we were in tents.”

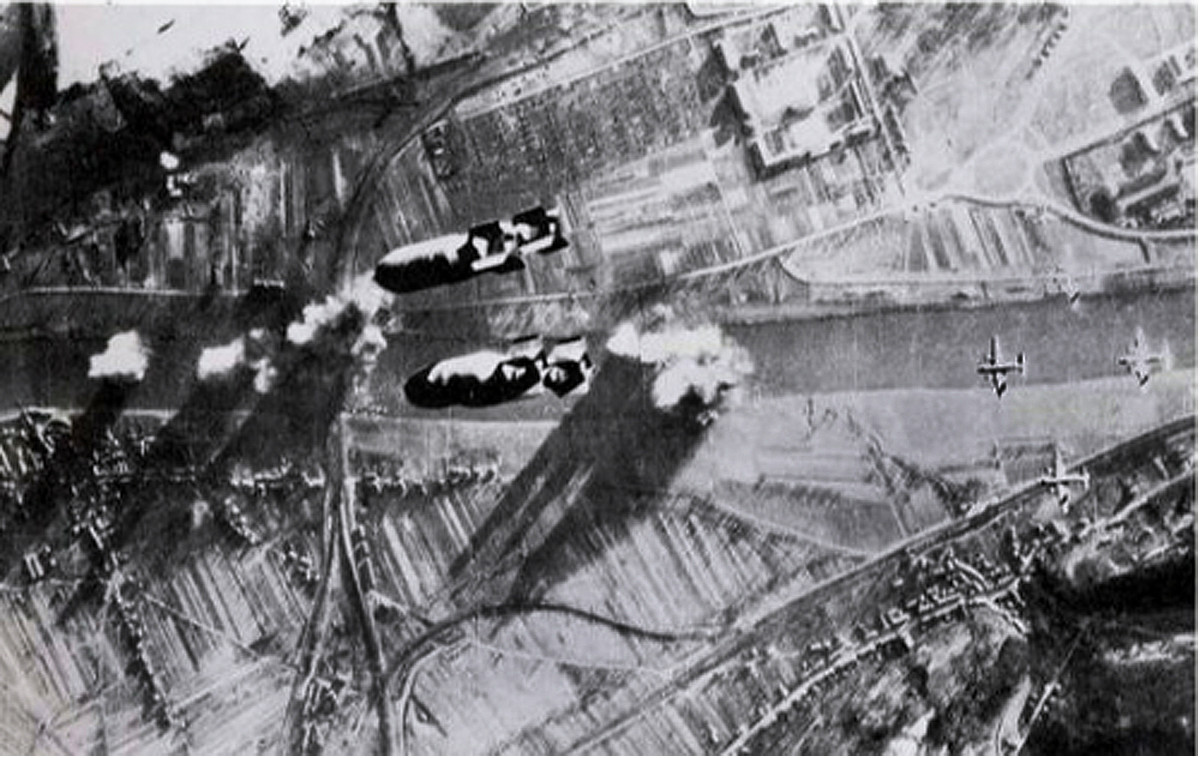

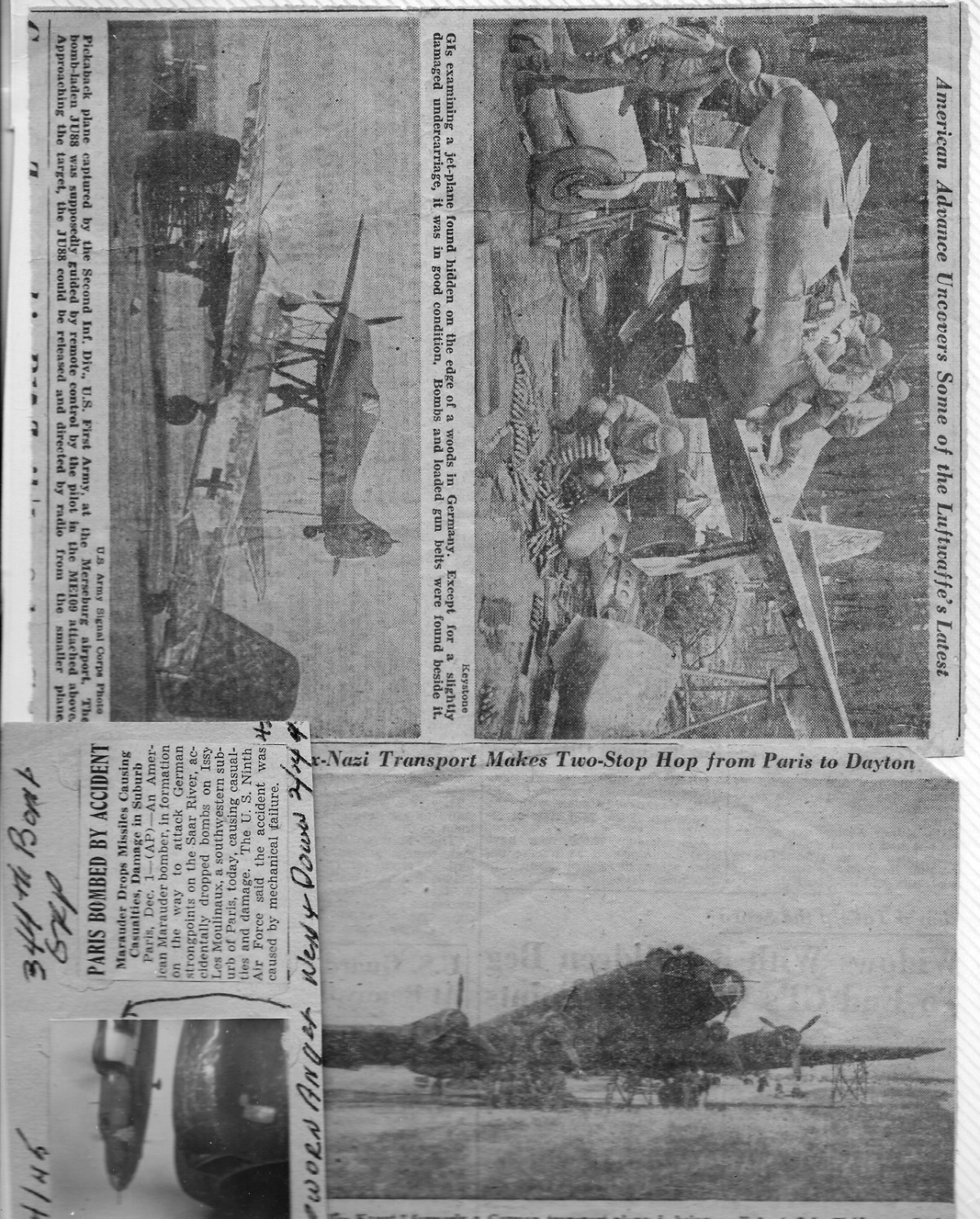

“In many WWII history books, they will show planes on fire, breaking in two, wings or engine blown off, or completely blowing up. During the battles with flak coming up, there were no crewmembers with a camera taking pictures. A certain number of the planes had cameras in the bomb bays to record where the bombs hit and the damage done, these cameras captured those pictures.”

“In many WWII history books, they will show planes on fire, breaking in two, wings or engine blown off, or completely blowing up. During the battles with flak coming up, there were no crewmembers with a camera taking pictures. A certain number of the planes had cameras in the bomb bays to record where the bombs hit and the damage done, these cameras captured those pictures.”

Bomber “Marauder” B-26, serial number 43-34565, Gratis Gladys, 7I-B, 497 Squadron, 344th Bombardment Group, 9th U.S. Air Force is crashing to the ground after receiving a direct hit in the left engine during the bombing of a Erkelenz, Germany, 26 Feb 1945. MACR 12649

“As I mentioned previously, our Intelligence people knew where most of the flak guns, numbers and positions, were. They knew this mostly through aerial photography and reports of being fired upon. We would be briefed on all these things, and be routed accordingly. From a certain point we would fly a certain compass heading, a certain length of time, take up another heading, for a number of minutes, continue this routine, zig-zagging to miss as much flak as possible. Didn’t always work but we tried. Once on the bomb run, you flew straight and level.”

“Towards the end of the war, a system was developed that enabled us to drop the bombs thru the clouds. There was a group who had received special training and special equipped planes, and with help of radio beams enabled us to hit the targets. On one fuel dump target, the smoke came swirling up, so we knew we were successful. On this type of mission our bomb run was approximately 25 miles long, so the Germans had a long time to try and bring us down. The Germans aimed their guns by radar. To counteract this problem, each group would schedule three planes carrying “window” (so called by the way we disposed of it). It was strips of aluminum 1/4 in. wide and 12 in. long, just like Christmas tree icicles. They came in small bundles. Approximately 30 seconds to a minute ahead of the group, these 3 planes flying about 2, 000 ft below the bomb group, made shallow ‘S’ curves. The gunners on both sides of the planes would toss the aluminum strips out, floating down by the thousands, and covering a very wide area. To the German radar, each strip, resembled the same reading as a plane, so they were unable to locate the group accurately enough to hit the planes. Earlier I mentioned, our part of the war was like a checker game, we knew the their intentions and plans, and they, knew ours. What would disturb me and I am sure many others, We would be scheduled for a window mission, get over Germany, to find the sky clear as a bell. The ideal decision would be to scrap the window schedule, and bomb the target visually. Some group leaders didn’t act intelligently. Rather than the bomb run being 2 miles long, we flew a 25 mile bomb run straight and level, the Germans loved it.”

Moomaws Combat Missions Certificates

Moomaws Combat Missions Certificates

E-mail Mr. Moomaw wrote to me;

1/24/2010 “Hello, thanks for your emails, when I joined the unit, we were not assigned a particular plane, there were more crews than planes, but mostly flew Y5W. Y5W crashed into the Alps in September 1945 with 8 men aboard, I believe the last B-26 to crash in Europe. We did fly Shopworn Angel on 2/12/45 and our tail gunner was killed by flak, guess, the sign of things to come. I joined the unit in Pontoise, France in October 1945. ”

9/15/2010 “Hi Carl, another photo I discovered, had it filed away separately, was going to send it to his family, but could not locate them. Tech, Sgt. Vanderlug, tail gunner, this was taken on Feb. 12, 1945 prior to taking off on a mission. Why taken, and why only him, he was killed on that mission????????? Did he or someone have a preimision of what was going to happen???? And it Feb.14th that Shopworn Angel went down. ”

9/16/2010 “There is no question Sgt. Vanderlug was killed on that mission, he was on our crew, I can remember as clear as if it was two hours ago, He came on the intercom, I have been hit, I have been hit. We immediately requested information to the nearest airfield that could give him medical aid. I do not remember the airfield, he was alive when the medical personnel took him. He was a very good individual, but flak is not choosy.”

9/17/2010 “On February 12, 1945 I was in Shopworn Angel, I do not know what plane I flew on Feb.14th, at this time we were not assigned regular planes, my log book for the 14th would only show a serial. number. not the name or a Y5 number. ”

9/20/20

Carl asks Don,

Take a look at the info sent to me (below) from a historian friend of the b-26 community. He’s got the date at February 10. No big deal, I just like to nail down these details while I still have people like you who can help me. Don, do you have any memory of the nose art being changed on the Shopworn Angel and why? I’ve got two designs and I’m trying to sort that out.

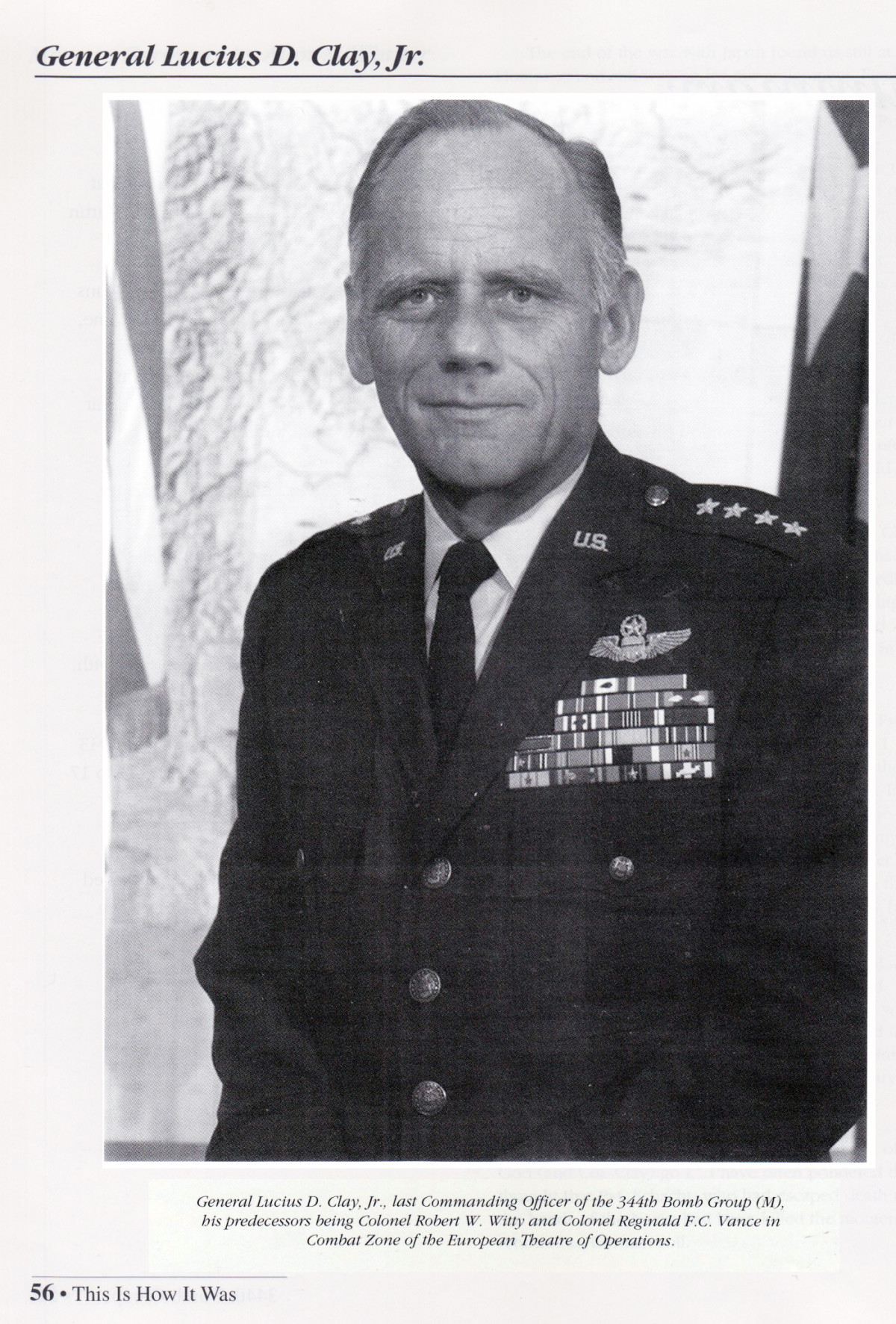

“The nose art was not changed to my knowledge. the photo of the plane when Capt. Clay crash landed was the same. Major Clay was leading the group on the mission that Shopworn Angle went down.”

6/1/2012

“HELLO CARL, THANK YOU FOR YOUR EMAIL, I AM ANXIOUS TO HEAR ANY NEW NEWS CONCERNING THE FEBRUARY 14, 1945 MISSION. THE ATTACHED PHOTO. THIS WAS OUR TAIL GUNNER CORNELIUS VANDERLUG. WHY I TOOK THIS PHOTO , AND WHY ONLY HIM IS A MYSTERY. THIS WAS TAKEN PRIOR TO TAKE OFF ON A MISSION ON FEBRUARY 12, 1945, I DON’T RECALL THE TARGET. HE WAS KILLED ON THIS MISSION. WHY????. HE HAD ONLY HOURS TO LIVE????. TRULY A MSTERY.