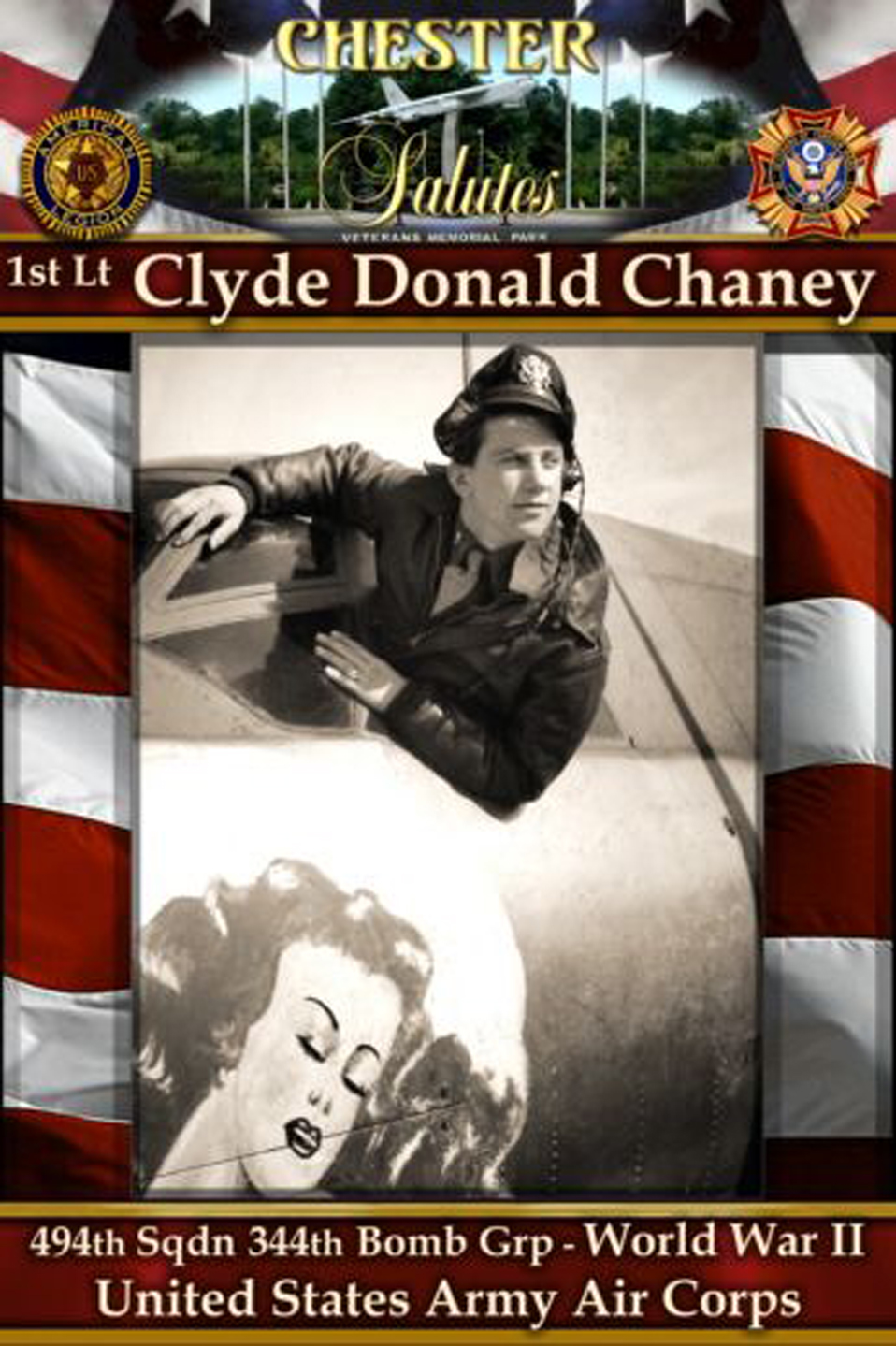

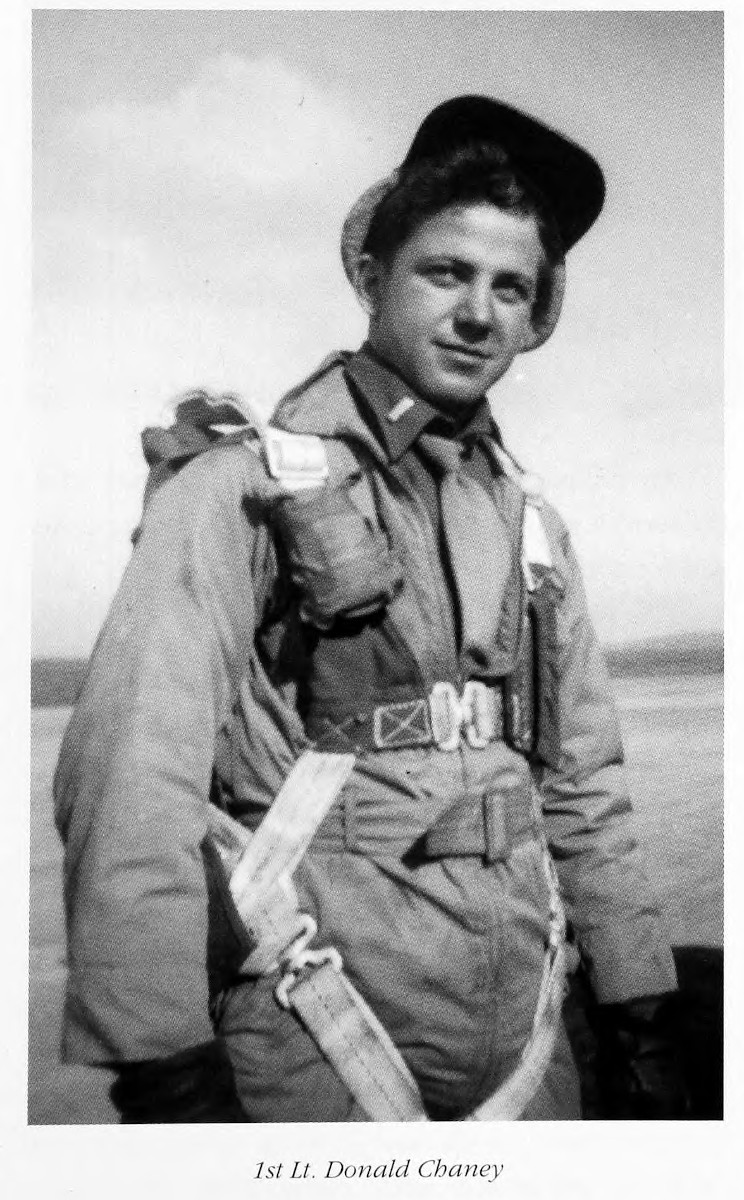

Lt. Clyde Donald Chaney

Clyde Donald Chaney

Over and Out

by Don Chaney –

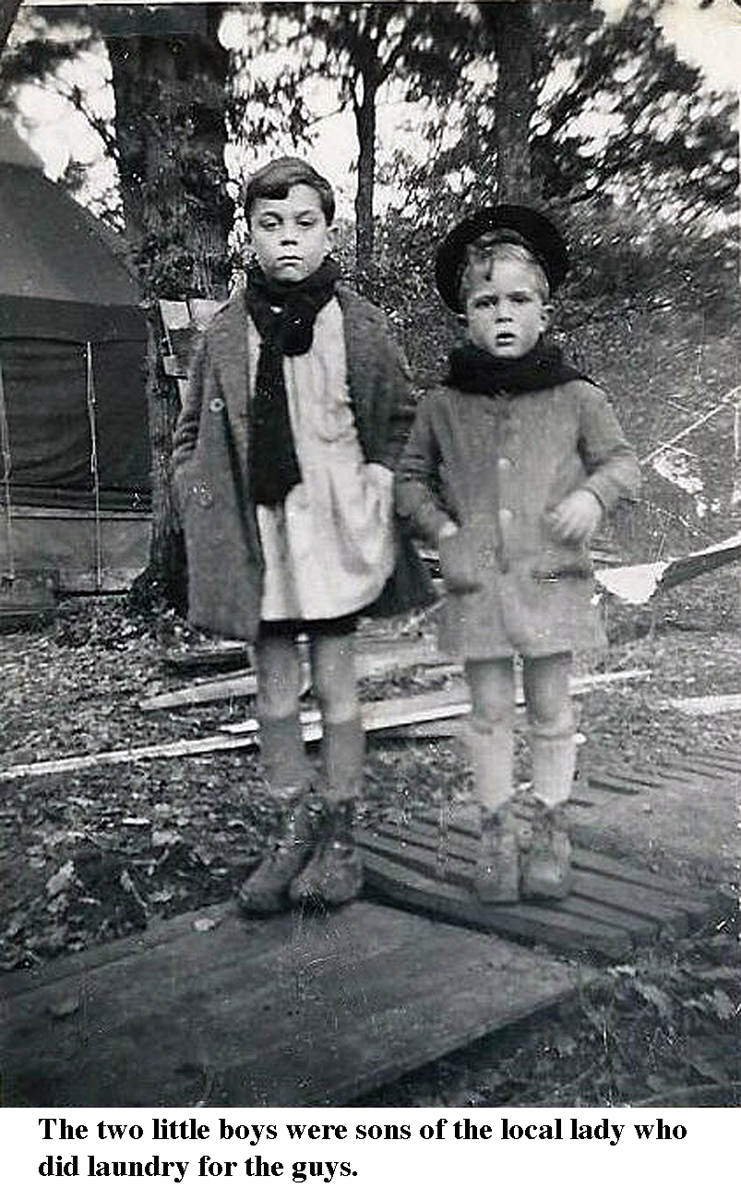

My dad, Clyde Donald Chaney died at the age of 92 on October 1, 2014 at his home in Chester, West Virginia. He served as a pilot in the 494th Squadron of the 344th BG. His first mission was D-Day +1 and he went on to fly 65 missions. He was 23 years old when he came home to marry his childhood sweetheart, Mary. Together they raised 7 children who gave him 24 grandchildren, who in turn gave him 36 great grandchildren…so far. He and Mom celebrated their 69th wedding anniversary in heaven on October 27.

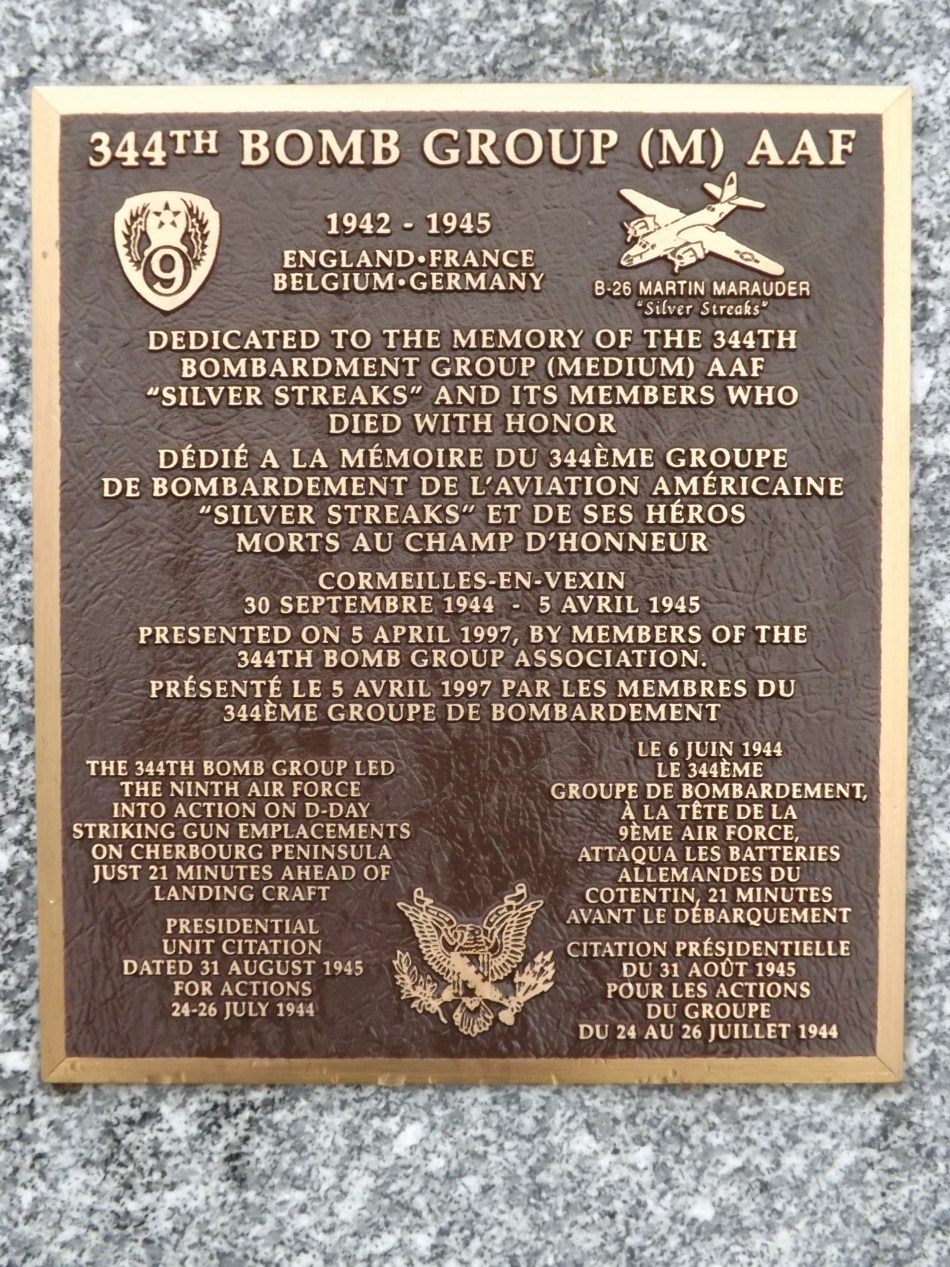

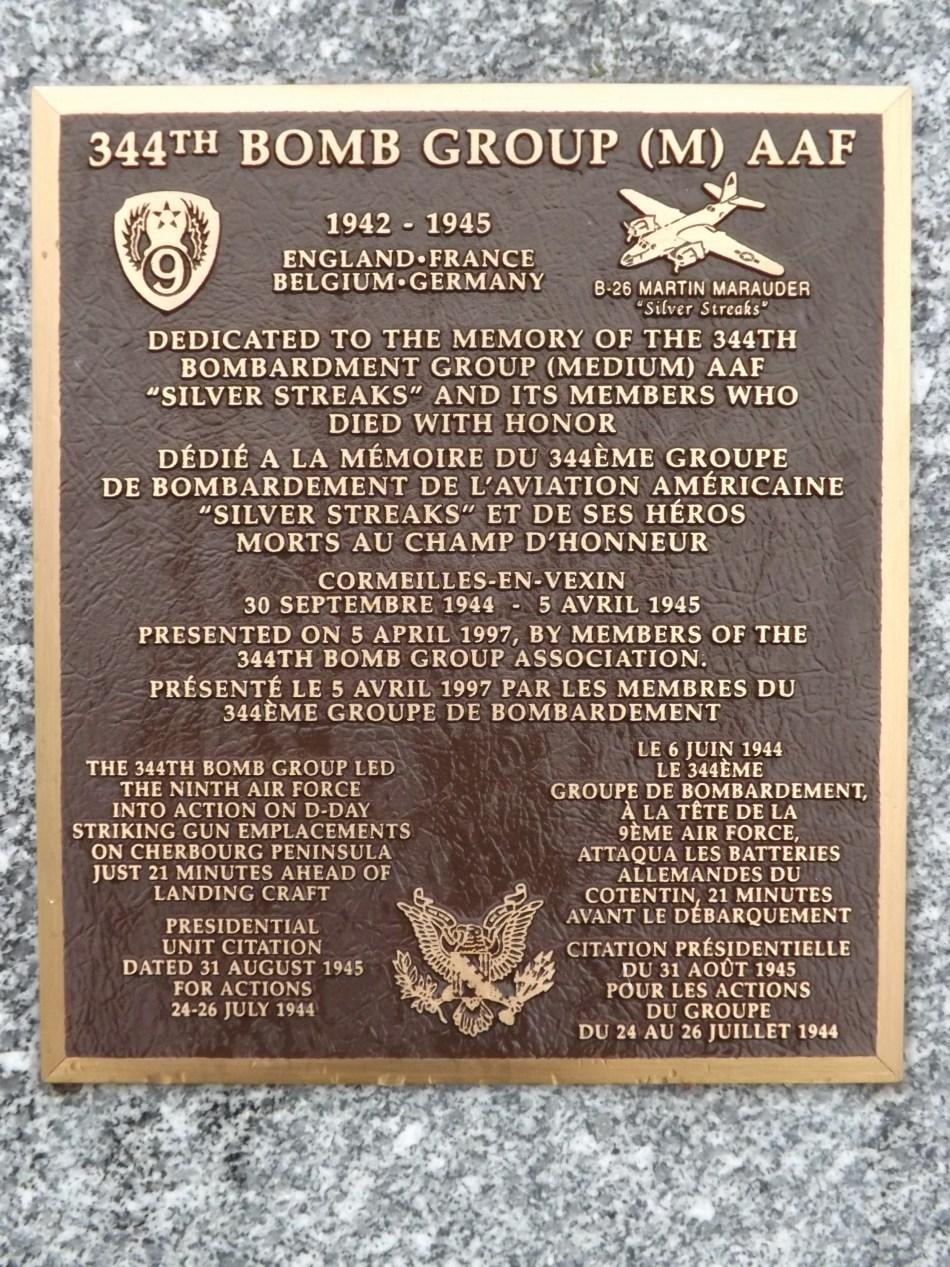

Dad loved his flying buddies and always looked forward to seeing them at reunions. He enjoyed their poker games and their camaraderie during that long, cold and dangerous winter of 1944-45. He maintained lifelong friendships with many of the guys, most of whom are gone now. In 1995 after a visit to old Station A-59, he started the ball rolling to have a monument placed at what is now the Cormeilles-en-Vexin Aerodrome, near Pointoise, France.

A wonderful ceremony was held at the airfield in April 1997 to honor all of the brave young men who risked and lost their lives in the cause of freedom. Many members of his bomb group and their families attended the moving event along with mayors of surrounding villages and their citizens who promised never to forget the men who spent time in their neighborhoods so long ago.

Dignitaries from the French military as well as free French aviators and their families were also present.

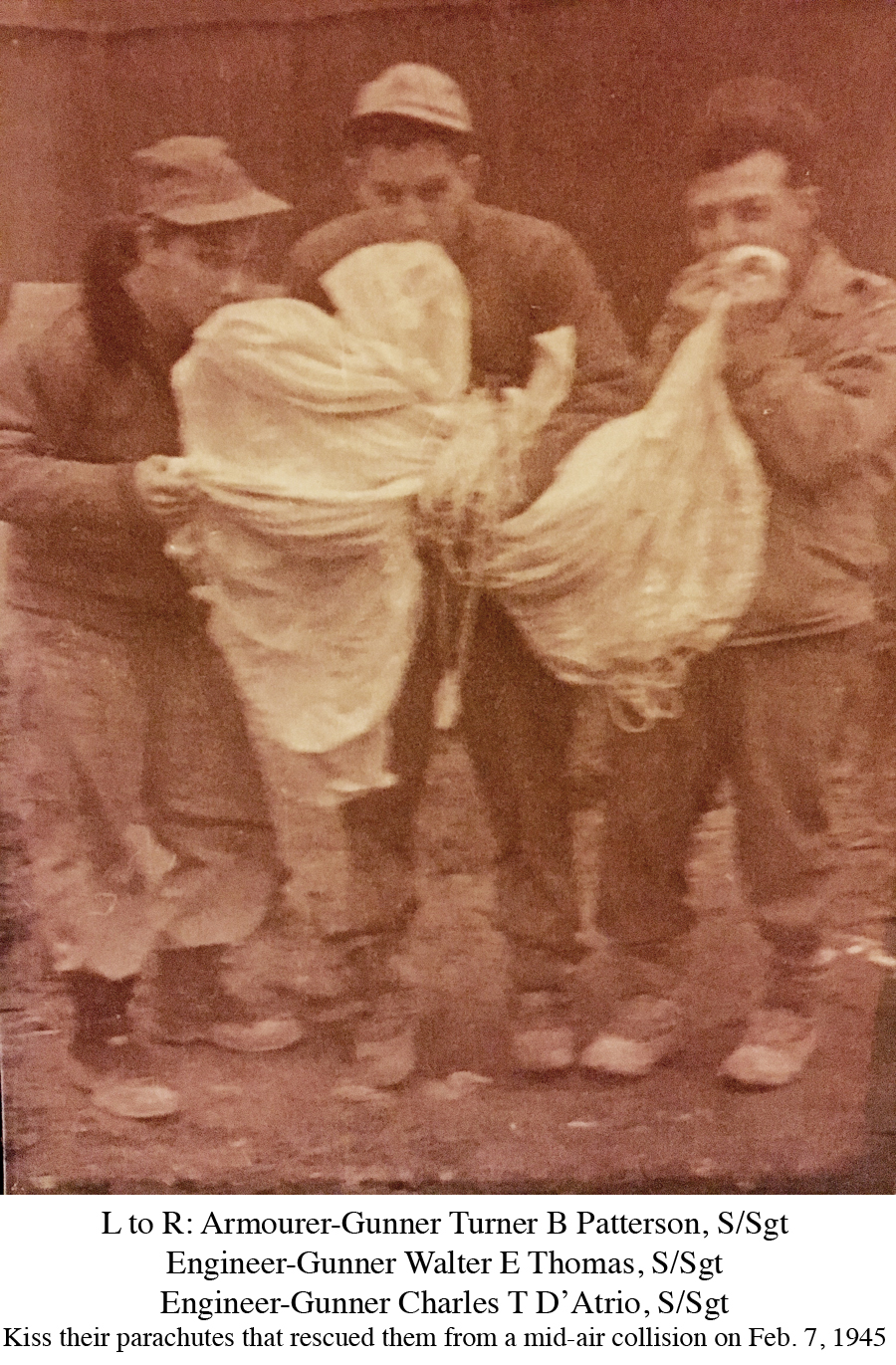

Dad’s time at Station A-59 was not without mishap. On February 6, 1945, his bomb group had finished a mission attacking the Rheinbach ammo dump. Dad was co-pilot. Returning home, their plane was diverted to Station A-73 Roye/Amy Airfield due to bad weather conditions. They were eventually ordered to return to home base. The weather was so bad at A-59 that the plane was again diverted to another airfield, Station A-60 Beaumont-sur Oise. According to the accident report, one of the pilots reported that visibility at the field was zero straight ahead. The field could only be seen by looking out the side window while banking to the left. Radio reception at that time was reportedly very poor and unbeknownst to either crew, both B26s were circling the field in the same pattern attempting to land. Both planes suddenly loomed out of the clouds. Both pilots attempted to avoid a collision but the wing of one plane hit the tail of the other plane, severely crippling both aircraft. Dad’s pilot managed to get their plane up to about 1500 feet and all crew bailed out safely. Dad said that right after the mid air collision, the crew came toward the cockpit. Dad said that he put the wheels down, opened the hatch and they bailed out through the nose wheel-well. The other pilot got up to around 3500 feet and the entire crew parachuted to safety. The incident was chalked up to bad weather conditions. Both planes were totally destroyed. About ten years ago, at a reunion of the bomb group, Dad and I met the 18 year old waist gunner from the other plane. He was from Ohio and went home to have a large family like Dad’s. On page 345 of Lambert D. Austin’s book, there is a picture of Sergeant Patterson, one of the other crew members from the other plane. He’s standing there with his open parachute, on February 7, 1945 the day after the collision.

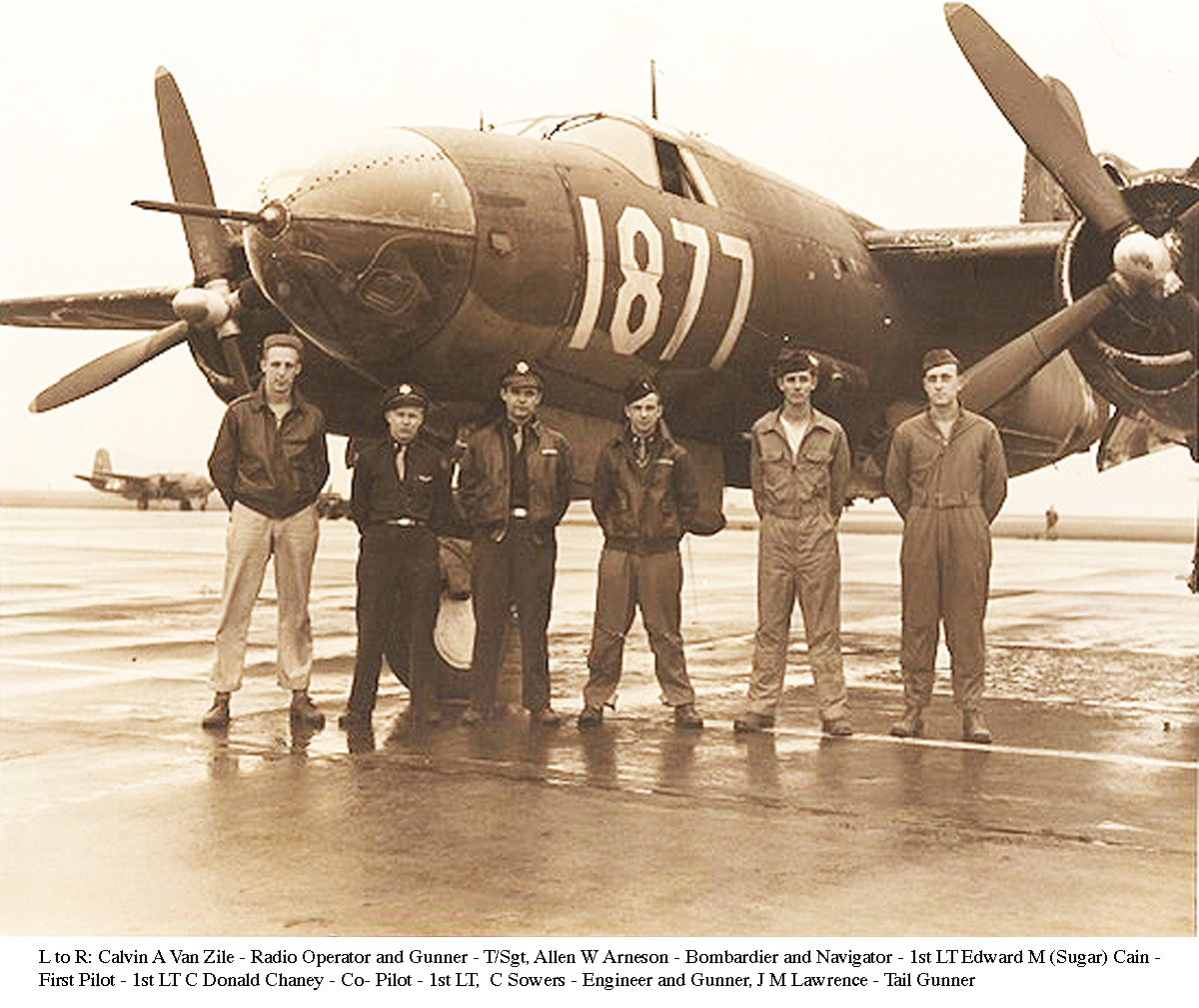

According to the report, the crew lists for the two planes were:

According to the report, the crew lists for the two planes were:

494th of 344th

Pilot Edward M Cain, 1st Lt. (Dad called him “Sugar” Cain)

Co pilot Clyde Donald “Don” Chaney, 1st Lt. (My Dad)

Bombardier Allen W Arneson, 1st LT

Engineer-Gunner Carroll Sowers, S/Sgt

Radio-Gunner Calvin A Van Zile, T/Sgt

Armourer-Gunner Clarence Robertson, S/Sgt

494th of 344th

Pilot. Conrad C Oberg, 1st Lt.

Co-pilot Robert D Conrad, 2nd Lt

Engineer-Gunner Charles T D’Atrio, S/Sgt

Engineer-Gunner Walter E Thomas, S/Sgt

Radio-Gunner William R Skinner, Jr., S/Sgt

Armourer-Gunner Turner B Patterson, S/Sgt

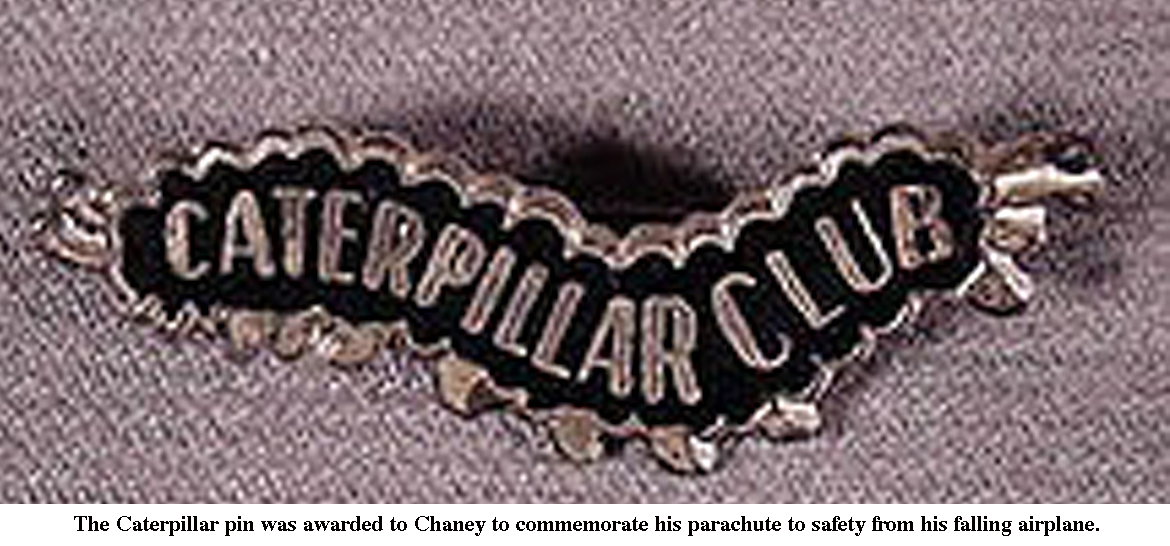

Caterpillar pin was awarded to flyers who had to parachute out to save their lives. Dad wore his proudly and gratefully.

Memories of a Marauder Man by Clyde Donald Chaney

I am writing in regard to my experiences on the way to D-Day and beyond.. I was twenty years old when I enlisted in the Army Air Corps on June 22, 1942 at Bowman Field, Louisville, Kentucky.

I was twenty one when I received my commission and wings as 2nd Lt. I was assigned to B-26 school at Lake Charles, Louisiana where I was assigned as a co-pilot with five other airmen. The pilot was from Alabama, the bombardier from North Dakota, the engineer from Kentucky, the radio operator from New York and the gunner St.Louis. After our training we were assigned to Hunter Field, Georgia. We were assigned a navigator there. The bombardier and gunner were sent overseas by boat. We picked up a new B-26 at Hunter Field and flew to Homestead, Florida. From there it was on to Puerto Rico and then on to British Guiana. We flew in the mornings because of bad thunderstorms in the afternoon.

I was twenty one when I received my commission and wings as 2nd Lt. I was assigned to B-26 school at Lake Charles, Louisiana where I was assigned as a co-pilot with five other airmen. The pilot was from Alabama, the bombardier from North Dakota, the engineer from Kentucky, the radio operator from New York and the gunner St.Louis. After our training we were assigned to Hunter Field, Georgia. We were assigned a navigator there. The bombardier and gunner were sent overseas by boat. We picked up a new B-26 at Hunter Field and flew to Homestead, Florida. From there it was on to Puerto Rico and then on to British Guiana. We flew in the mornings because of bad thunderstorms in the afternoon.

We flew on to Natal, Brazil and then onward to the Ascension Islands in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. The next stop was at the tip of Africa and then on to Marrakesh, Morocco. We spent ten days there waiting for the right wind to fly. This was the first time I saw thousands of prisoners. Italian prisoners behind chain link fences begging for cigarettes.

We had a briefing in a schoolroom where Clark Cable’s name was carved in the table. He had been there before us. He was a gunner. From there we flew to England where we turned over our plane. We went on to Northern England and then to Scotland by train. Then we took a boat to Northern Ireland. From there we flew to Station A-59 airfield about thirty miles north of London. Nearby were the towns of Bishop’s Stortford and Stansted Montfitchet. The date was June 5, 1944. There were eight crews. We had picked up the rest of the crews in Ireland….four squadrons, eight crews who were replacements for the groups…..two crews to each squadron.

We were then ushered into Colonel Vance’s office. He welcomed us and told us he was glad to see us. He said he could not understand how we got onto the field because it had been closed. Our squadron was the 494th Bomb Squadron. Colonel Vance was the 344th bomb group leader. We later learned that he was known as the man who was worth his weight in gold. He got this name when he was in the Philippine Islands. General McArthur ordered him out on a submarine that was carrying gold. They had to take off the weight of Colonel Vance in gold so that he could go aboard.

We noticed excitement at the airfield. They were painting the planes for the D-Day invasion. So the next morning at two a.m. they shook us out of bed and we were briefed that it was D-Day and our group, 344th Bomb Group, was the first group of the 9th Air Force that led the invasion over France. . The weather was bad. Our targets were the fortifications along the beaches in Normandy. Our replacement crew flew two missions on D-Day+1. We went in at about four thousand feet and flak was light. We concentrated on Utah Beach. I never saw so many boats in all my life. The sky was full of planes. It was the beginning of my 65 mission tour of duty. .

My group later transferred to France to a base about 16 miles from Paris. I flew through the Battle of the Bulge on my 55th mission. I had to bail out of the plane when we collided with another B-26 in dense fog over France. Miraculously, all crew members in both planes survived. I finished my tour in March 1945. I had become a 1st pilot and was discharged as a 1st Lt. From Camp Atterbury, Indiana in May 1945. I was twenty two years old.

_____________________________

From 344th BG Silver Streaks by Lambert Austin- A First

It all started on December 29, 1944, at 4:30 in

the morning at Station A-59 in France. I was rudely

awakened by the duty clerk calling out that briefing

would be at 5:30 am. It was cold crawling out of my

sleeping bag onto the floor of our tent. I remember

hardly getting on my clothes and turning left to the

latrine. Coming back, I picked up my towel, toothbrush,

and mess kit and headed for the wash room

with a flashlight. I brushed my teeth in cold water.

From there I went to the mess hall, which was a tent with a small dim light bulb in the middle. It

was cold and dark. The cooks had prepared pancakes

and coffee and everything was cold.

Being a typical soldier, I bitched out loud about

how bad the food was. Then I heard a voice in the

corner of the tent speak out, saying, “Soldier, do

you think you could do any better?” I said, “I know

I could do better than this.” The person asked me

my name, and I said, “Chaney.” Not thinking any

more about it, I left the tent.

The next morning someone told me to go check

the bulletin board. The following was written

there:Squadron Order No. 39, dated 30 Dec. 1944.

First Lt. Clyde D. Chaney, 0 816 791 AC, is announced

mess officer (additional duty). Captain Emil A.

Seitzinger, relieved, ordered by Lt. Col. Thomas

Johnson, commanding.

This is how I found out I was the new mess

officer in addition to my flying duties.

1 went up to the mess hall and talked to the

mess Sgt. to find out what was wrong. He informed

me that the morale was low. Ordinarily, the food

was prepared between 6:00 a.m. and 7:30 a.m. for

the enlisted men and between 7:30 a.m. and 8:00

a.m. for the officers. Dinner for the enlisted men

was served from 11:00 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and from

12:30 p.m. to TOO p.m. for the officers. Supper was

from 5:00 to 6:30 p.m. for the enlisted men and 6:00

p.m. to 6:30 p.m. for the officers.

I then changed the time and eating arrangements.

All men, both enlisted and officers, should eat together,

since we were all fighting the same war.

This change gave the cooks more time to prepare

the food and then to have more time off when the

meal was done. All eating was from 7:00 a.m. to

8:00 a.m., 12:00 p.m. to TOO p.m. and 5:00 p.m. to

6:00 p.m.I did have problems with the mess Sgt., and

things happened that would be better left unsaid.

He was removed and sent on.

I then went to the mess hall and approached a

corporal. I asked him if he would like to become

the new mess Sgt. It would mean more stripes for

him, 1 explained. He said, “yes.” I then asked him

where he was from and he said, “Oh, you wouldn’t

know.” I said, “Try me.” He said, “A small town in

West Virginia.” I said, “How small?” He told me he

was from New Cumberland, West Virginia, which, it

just so happened, was just ten miles from my own

hometown of Chester, West Virginia.

My troubles with the mess hall were over. My

Squadron Executive Officer informed me we could

get a wooden building for a mess hall, which we

did. He also told me we could get Italian prisoners

to do K.P. duty, which we did.

Later we learned that the Germans had stored

all kinds of supplies in caves, including dishes. We

got a truck and loaded it with the dishes for the

mess hall. No longer did we have to dip our mess

kits down into 55 gallon drums; we now ate on

plates.

I felt that when a flyer finished his 65th mission,

he should have something special done for him.

Therefore, a table was set for him with a white tablecloth

and candles, and the best food was served to

him, including a bottle of wine and cake. As far as

I know, this tradition was carried on after I left.

1 was told by our Mess Sgt. Joseph Zimia that

after I left, another flying officer was appointed as

mess officer. 1 still keep in touch with Joe, who

now resides in Wheeling, West Virginia, and who

received the bronze star.

As far as I know, I was the first mess officer

who was also a flying officer in the whole Ninth Air

Force. My feeling was, give the Army good food, and

the morale will be good. As the old saying goes, the

Army travels on its stomach.

P.S. We were the Army Air Force.

– C. Donald Chaney

494th Bomb Squad.

_____________________________

Note from Jean Bell: When Dad and my husband and I were in France in 1997 for the dedication of the memorial at the airfield at Cormeilles-en-Vexin, we were privileged to meet Mr. John R Stokes of California. The late Mr Stokes was a distinguished attorney and recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross with ten Oak Leaves.

We rode the train with him from Pointoise back to Paris. Mr. Stokes told us about a harrowing experience he had while flying his plane along the same southern route across the Atlantic that my Dad had flown. Somewhere out in the middle of the Atlantic he had to ditch his plane due to engine problems. The crew climbed in their raft and hoped against hope that they would be found and rescued. I remarked, “Well at least you had water and some food.” Mr. Stokes replied, ‘Well yes, we did until a big wave came along and overturned our raft. We lost everything.” Fortunately, they didn’t have to float around too long. Another B-26 flying near to them saw them go down and made note of their location. The crew was rescued and had to return to America to pick up another plane. Mr. Stokes said they suspected sabotage.

__________________________

In October 1995, we were in England and paid a visit to Station 169 STANSTED MOUNTFITCHET , now the site of a busy international airport. We were given a tour around the field in a jeep and saw remnants of some old Quonset huts and bits of old runway. The manager of the airport showed us through the facility and led us to a glass case in the main hall. The case was full of World War II memorabilia commemorating the anniversary of D-Day. Suddenly, my Dad leaned over the case and exclaimed “there’s my name!” He was pointing at an old journal. A closer look revealed the journal to be the log of the airbase’s commander. The journal was opened to June 6, 1944 and the commander’s entry reported the welcome arrival of a replacement crew who had arrived from Ireland. Among the men listed was the name of Clyde Donald Chaney! What a serendipitous moment.

Dad would tell you that he led a wonderful life and that he considered himself to be a very blessed and lucky man. I can’t disagree.

Donna Chaney Bell

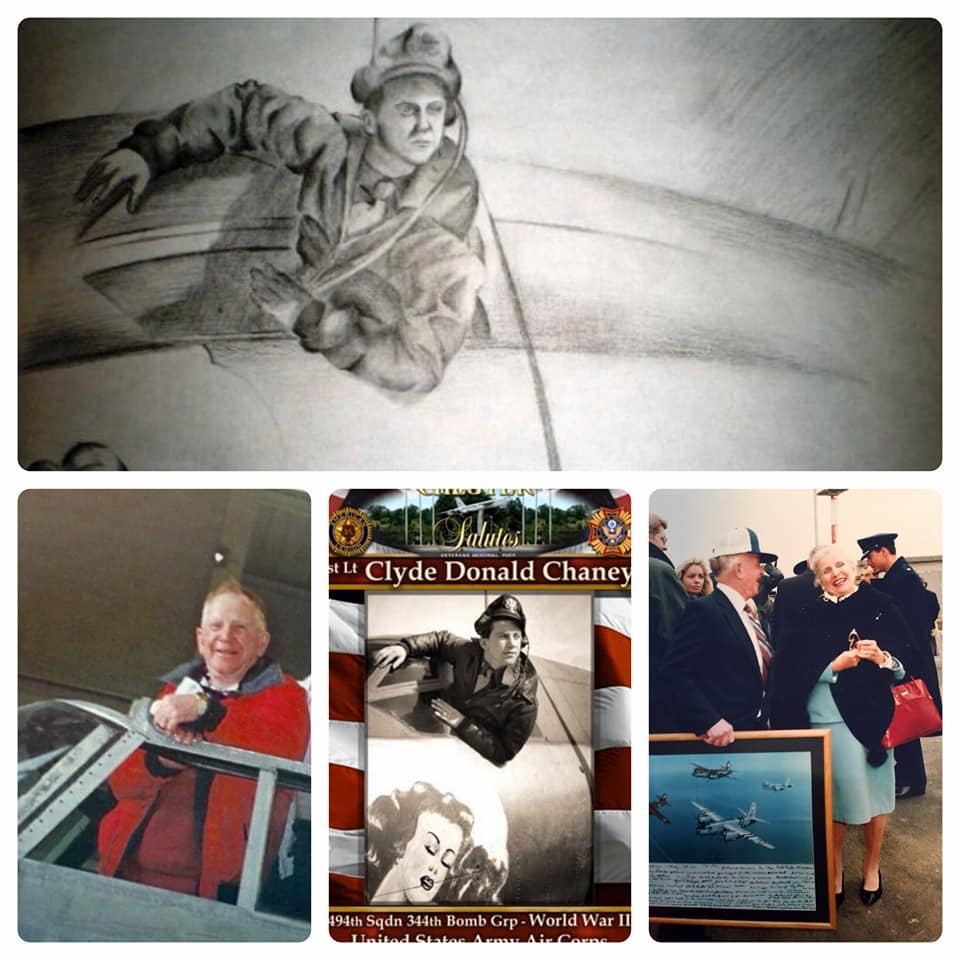

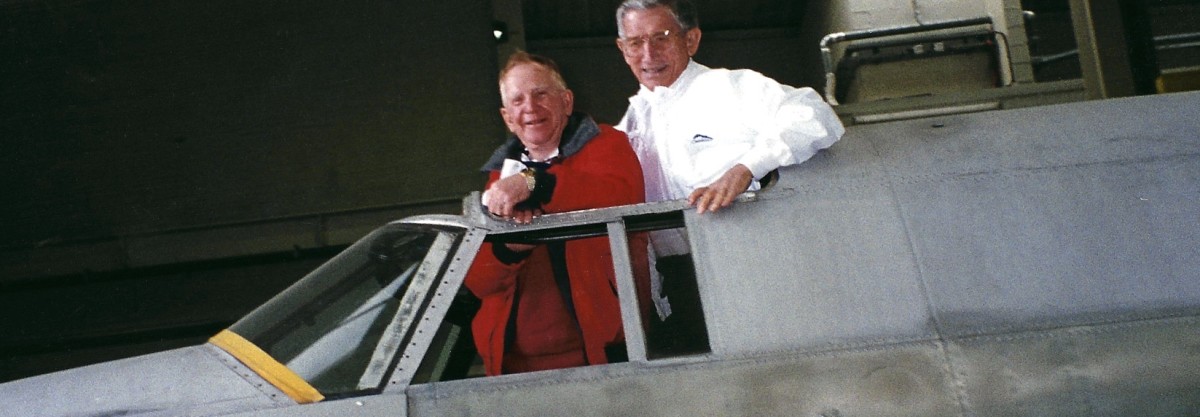

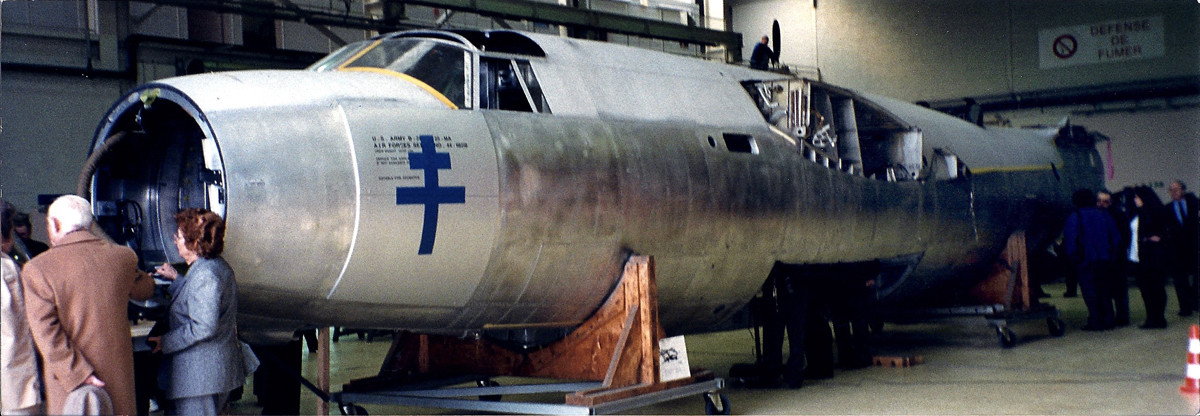

Pilots Don Chaney and Don Korkowski check out a B-26 under restoratrion at Le Bourget Airfield, Paris April 1997

.

B-26 being restored by free French airmen.

Memorial Ceremony at Cormeilles-en-Vexin, April 1997

Presented in ceremony at Station A-59, April 1997

.

.Chaney Video: Click here to see the group sing a song written by Clyde. In this clip from a video that my husband made when we met Mr. &Mrs. Morton on a trip to France in April 1997. We were there for the dedication of the monument at Station A-26 at Cormeilles en Vexin. The group is at the Arc de Triumph.

Dad is in red jacket. Group of men in video are Robert Moore, Dad, Robert Camby of Free French flyers, Korky Korkowski, Austin Lambert, Bill Morton and several Free French men.

In the video, Lt. Clyde Chaney is the man in Red jacket and blue ball cap standing behind the Mortons as they sing. He was very involved in getting the ball rolling for the monument at the airfield. Had his daughter Jean Bell, writing the head of French airports for permission to place the monument.

From a post by Jean Bell regarding Donald Chaney: “This photo has a drawing of Dad done by his grandson Ethan Dray. Also Dad in the cockpit of B-26G “Dinah Might” being restored at Le Bourget Air Field by Free French Flyers in 1997. The plane has since been moved to the Utah Beach Museum in Normandy. The middle photo is Dad, Donald Chaney. And the last photo is Dad and Madam Wallet who lived near the airfield as a young girl. The picture of B-26s signed by many who flew the planes still hangs in the tower at the airfield in Cormeilles en Vexin. Dad was a copilot who flew 65 missions.”

.

1st Lieutenant Clyde Donald Chaney, co-pilot, age 21, 494th Sqdn, 344th Bomb Grp.-arrived at the airbase in Stansted, England on D-Day and flew his first mission over Utah Beach, Normandy the next day. He went on to fly 64 missions and survived a mid-air collision over France.

Dad’s service history came to the attention of Jean-Dominique Le Garrec, Pittsburgh’s honorary consul of France when he met Dad at a meeting of the Pittsburgh Veterans Breakfast Club. The club provides a forum where area veterans can share their stories which are then archived for future generations. Monsieur Le Garrec contacted me around D-Day in the summer of 2014 saying he had a token of appreciation he wanted to give to Dad in recognition of his service. He then brought a citation from the French and Belgium communities of Pittsburgh to my home since Dad was out of town. This video shows me presenting the citation to Dad. Notice his hat which he wore everywhere. Shortly after this event, Dad fell and broke his femur. He never fully recovered and he passed away on October 1, 2014 at the age of 92.