Lt. Bennie D. McSwain Jr.

The Crew Forms (written by McSwain’s co-pilot Emlen L. Martin)

—–The six men who were to become one of many sent to the European Theatre as replacements for possible D-Day casualties first met at Barksdale Army Air Field in early 1944. The first pilot was Bennie D. McSwain from Little Rock, Arkansas; the navigator/ bombardier, Wilmoth L. Keller from Kansas; the radio/gunner, Achilles A. Principe from Brooklyn, New York; the engineer/gunner, Raymond P. Novis also from Kansas, and the armorer/gunner, James G. Ehlert from Waterproof, Louisiana. I grew up along the Delaware River in Bristol, Pennsylvania. Years later we all ended up in Colorado, California, Florida, Idaho, Texas and New Hampshire, respectively, all having returned safely to the USA after VE Day.

My first flights in a B-26 Marauder took place at Barksdale shortly before we were shipped as a crew to Lake Charles AAF, Louisiana, to undergo formal operational training. One flight during this period remains vivid; it was a cross-country exercise to Oklahoma City. The flight was uneventful until we attempted to depart Oklahoma. During our preflight we encountered engine difficulties. The engine was checked by the ground crew and, shortly, we were cleared for takeoff, but again the engine backfired and lost power. This time it underwent a more thorough examination taking most of the day and again OK’d. The next clay, McSwain, Novis and I prepared to test fly the aircraft. Preflight appeared normal, so we taxied to the takeoff runway where a good runup of the engines boosted our confidence. The takeoff roll went beautifully but, just as we broke ground, we experienced terrible vibrations with intermittent loss of power. We had to struggle for control and, after barely clearing the trees, we gently turned back towards the field, never able to rise more than a few feet above the tree tops. McSwain accomplished a masterful emergency landing and, as we rolled to a stop, we saw fire trucks and ambulances which had scrambled because of the noise of the backfiring engines. We were shaken. The other crew members had watched the test and had held their breath as they momentarily lost sight of us behind the hills and trees during our shallow circle back to the field. The engine was replaced before the plane could return to Lake Charles.

Welcome to the ETO

As soon as the training at Lake Charles was completed, we were sent by train to Hunter Field, Georgia, to pick up a spanking new B-26 Marauder. By this time D-Day had occurred, and we headed for Europe by way of the Northern Route stopping in Maine, Labrador, Greenland, and Iceland. When we arrived at Stansted AAF near Bishops Stortford, England, we were ready to join into the fray with our new aircraft, but instead we were shipped off to Northern Ireland for a couple of weeks of Theatre Indoctrination and were relieved of our aircraft. When we returned, we were assigned to a war-weary plane called “PATCHES,” a name derived from the overabundance of repairs covered by yellow paint — Welcome to the New Kid on the Block! Nevertheless, “PATCHES” worked out well, and we flew it on most of our missions up to the time it was crash-landed by another crew.

Combat Begins

Our initial combat experience was also an indoctrination in that each of our crew flew with a different experienced crew. The briefings, marshaling of aircraft, and formation join up on the first mission were so impressive that my feelings were more of fascination and excitement than of apprehension or fear.

These feelings persisted even as we entered enemy airspace and started to encounter intense flak. Further on, a few bursts of flak appeared pink, a signal for enemy fighters to engage us. I never saw them that day, either our fighter escort stopped them or they never pursued us. During our bomb run, when I glanced out the windscreen beyond the pilot, I was startled to see the profound change in his countenance. It was of such extreme tenseness that he was perspiring heavily even though it was bitterly cold. This brought home the fact that this was serious and hazardous business. It happened to be the pilot’s 65th mission. He had been wounded twice on other missions. If he made this one, he would be going home. Thankfully, he did. At the hardstand the group crew presented me with a chunk of flak that had creased the back of my seat, having traveled upwards and lodging in the structure overhead without touching me. (I immediately got a piece of steel shaped to fit beneath me on “Patches” for future missions). I never did keep the souvenir presented to me nor did I keep another that came through my windscreen on another mission to be stopped on my chest by my flak suit. Aside from superficial cuts from splintered plexiglass and near frozen fingers, I remained unharmed during my tour of duty as did the rest of my crew. We didn’t think this would be the case for our Radio Gunner, A.A. Principe. One day we were violently struck near the Waist. A shell or large fragment passed through the airplane and, in transit, cut the flak suit and clothing completely away from his shoulder. He, for quite a few seconds, couldn’t respond to queries from Jim Ehlert, our tail gunner, or from me; this silence alarmed us, but mercifully, he was unharmed.

On another early mission we found ourselves running short of fuel on our return. Fortunately we located an airstrip on the Normandy shore above the beaches. It was made of pierced steel planking, and only partially completed, nevertheless, we got permission to land. This became one of the first bombers to safely land and takeoff from a US airstrip in occupied France. We had to remain overnight and could hear the artillery near the front lines. The construction crew set up a tent, fed us, and using Jerry cans, provided enough fuel by hand for our return to England. It was nice to be appreciated by such hard-working GI’s.

Off Duty

There was a certain devil-may-care attitude among many of the younger newcomers to Stansted. This attitude occasionally got some of us into difficulties and almost did one evening for Donald Glenn who had arrived at Stansted the day before. He and some others were tossing a makeshift ball back and forth the length of the bar in the Officer’s Club and, while darting a few steps to intercept an errant ball, tripped and slid headfirst for several feet before coming to rest on the shins of Colonel Vance, the group commander, who had just come through the doorway. It got very still for a moment, but Colonel Vance just stepped over the red-faced Glenn and proceeded to the bar. We never knew what his first thoughts were about his new replacement crew.

When we weren’t scheduled to fly, we could, occasionally, get passes to London. The effect of German bombs were everywhere and the V-1 buzz bombs and V-2 missiles had continued to plague the city. During the hours of darkness the searchlights and banks of antiaircraft rockets lit up the sky, aiming at the buzz bombs or the occasional enemy aircraft that had evaded the curtain of barrage balloons around the city. These sights made a lasting impression, and I still marvel at the grit of the British who withstood these conditions for so long.

During my stay in France we got the chance to visit local villages or, occasionally, Paris, a favorite destination and only a short distance from our field. A few of us visited the village of Marines (Seine et Oise) during their “Fete de Ste. Catherine” where we were the objects of curiosity to the youngsters and genuinely welcomed by all. Later, some of us were invited to the homes of local families where we tried our best to remember high school French.

We found that we could get occasional eggs and that wonderful French bread by providing them with the flour to make the bread. I have fond memories of riding out on a bicycle with a bit of flour and returning to the airfield with several baguettes, a great change from the powdered milk and eggs in our Army mess. Before returning from one of these forays, word had reached us about the start of the Battle of the Bulge. Rumors were rampant about enemy parachutists and, as I rode my bicycle along in the dark, I imagined enemy soldiers behind each tree and possible trip-wires strung across the road.

I remember most vividly a later three-day pass which allowed travel to Paris from Florennes, Belgium, on the 6th of May 1945. On the 7th, word came of Germany’s surrender. Hordes of people converged on every street with impromptu parades, cheers, and singing continuing uninterrupted for days. P-51s, one painted red, buzzed the Champs Elysee. The lights and fountains of Paris were turned on again after so many years of darkness and turmoil, and you could once again appreciate the beauty of Paris.

Living Conditions

Our living conditions, while spartan, were never too bad and I was always thankful that I wasn’t in the infantry. In England the versatile Quonset huts served many purposes and proved an adequate shelter. After moving to the Vexin region of France (northwest of Paris) in September 1943, some of us in the 496th managed to make use of a long, single story wooden structure for living quarters. It was divided into a series of rooms off a hallway, accommodating two to eight individuals in double bunks. The entire structure backed on an artificial embankment that protected us from wind and made it more difficult to spot from the air. Coal and wood from the local area fed stoves in each of the rooms. We were quite comfortable through the harsh winter of 1944. This airfield near Cormeilles en Vexin had been a German base and an earlier target for our bomb group. Our building was about the only one left more or less intact. It was interesting that the airfield was well camouflaged with fake houses scattered about to make the place appear from the air to be a village.

Our group later moved to an airfield outside of Florennes, Belgium. While we initially were in tents, about a dozen of us set out to create better accommodations. Building materials were gotten primarily from derelict structures on the airfield, and soon we were housed in a three-room architectural wonder! There were two sleeping rooms with built-in bunks, each housing six to eight individuals on either side of the central lounge area. There was no running water, of course, but we did manage to string power to our new quarters. The squadron supply officer was among those in the group, and his help was extremely valuable in acquiring material and tools for this project.

Some Final Thoughts

Missions haven’t been emphasized in these recollections, though many left indelible impressions. Some were easy and some were terrible, but these events are best told in the personal diaries and in official records. One unique mission may be of interest since it involved a single aircraft. I was part of a pickup crew assigned to drop leaflets over enemy-held territory. The Calais area on the coast of France had been bypassed by our ground forces, and it would be our job to politely suggest through leaflets that the resistors should give themselves up.

Intelligence assured us that the Germans probably would ignore a single aircraft, so we could expect an easy sortie. We were somewhat skeptical and altered the plan laid out for us. We approached the target at an altitude of a few thousand feet higher than briefed and, putting the aircraft in a shallow dive, arrived over the target to deliver the leaflets at the prescribed altitude but, at near red-line speed. Suddenly our single plane became a center of attention and we were engulfed in black smoke (as related to us from another air crew a few miles distant). Even at this speed we sustained numerous hits, for example, about a dozen holes formed an arc around the turret gunner’s head. His exclamations were loud and continuous about this EASY mission. No one was hurt, and we quickly left the area congratulating ourselves on some foresight.

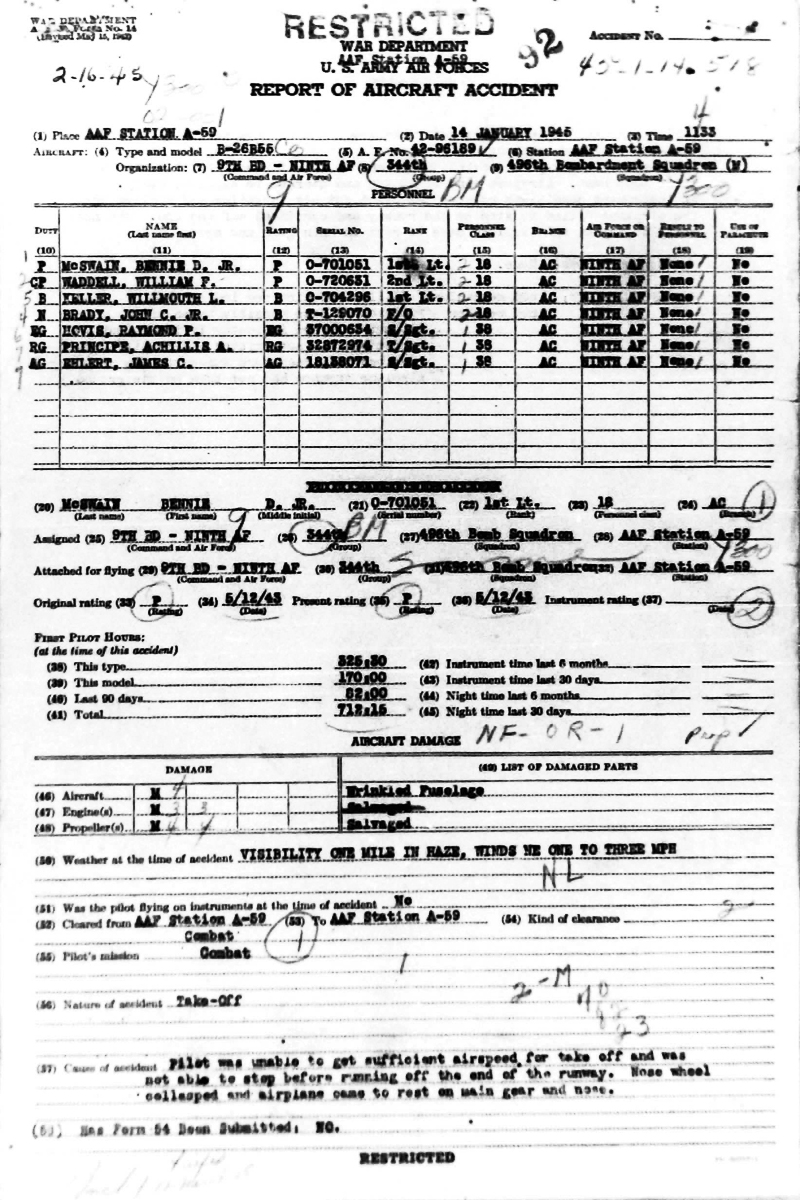

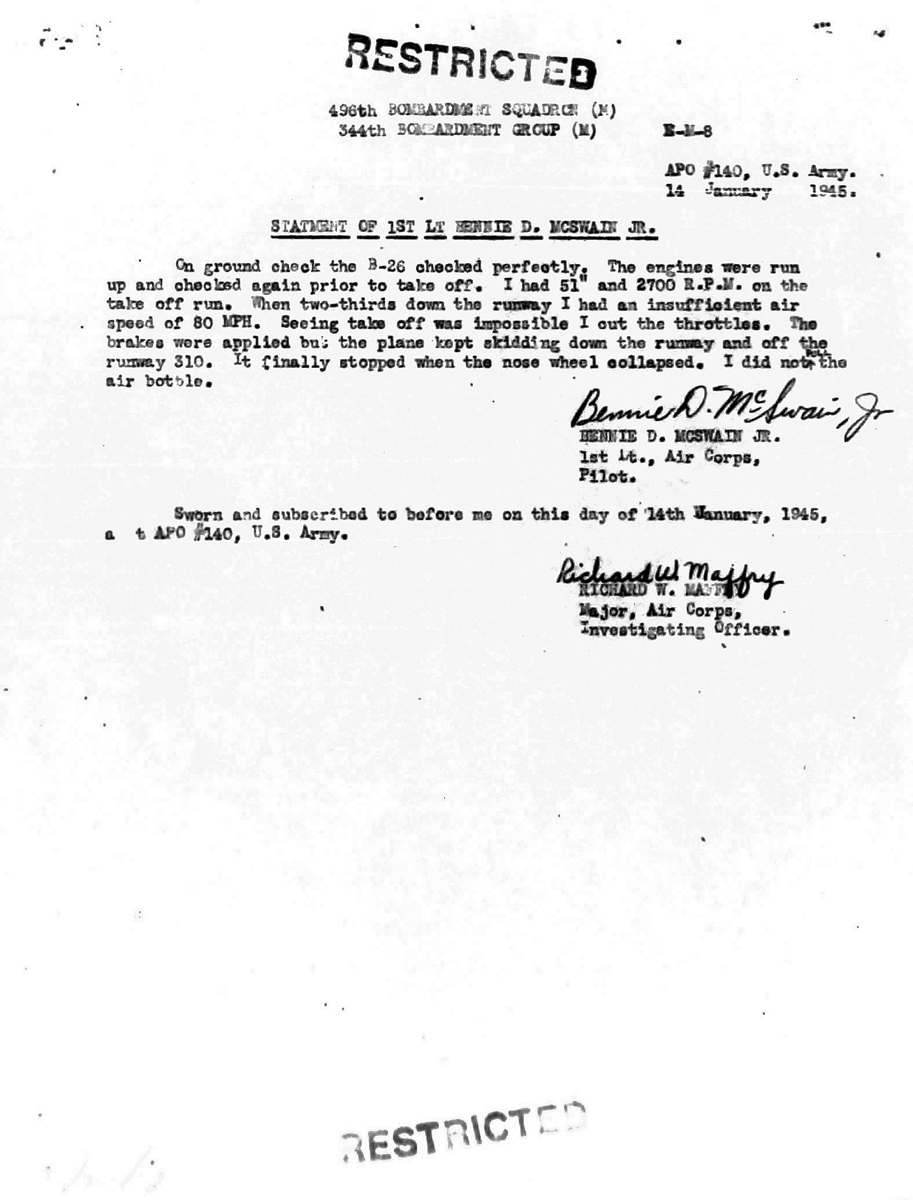

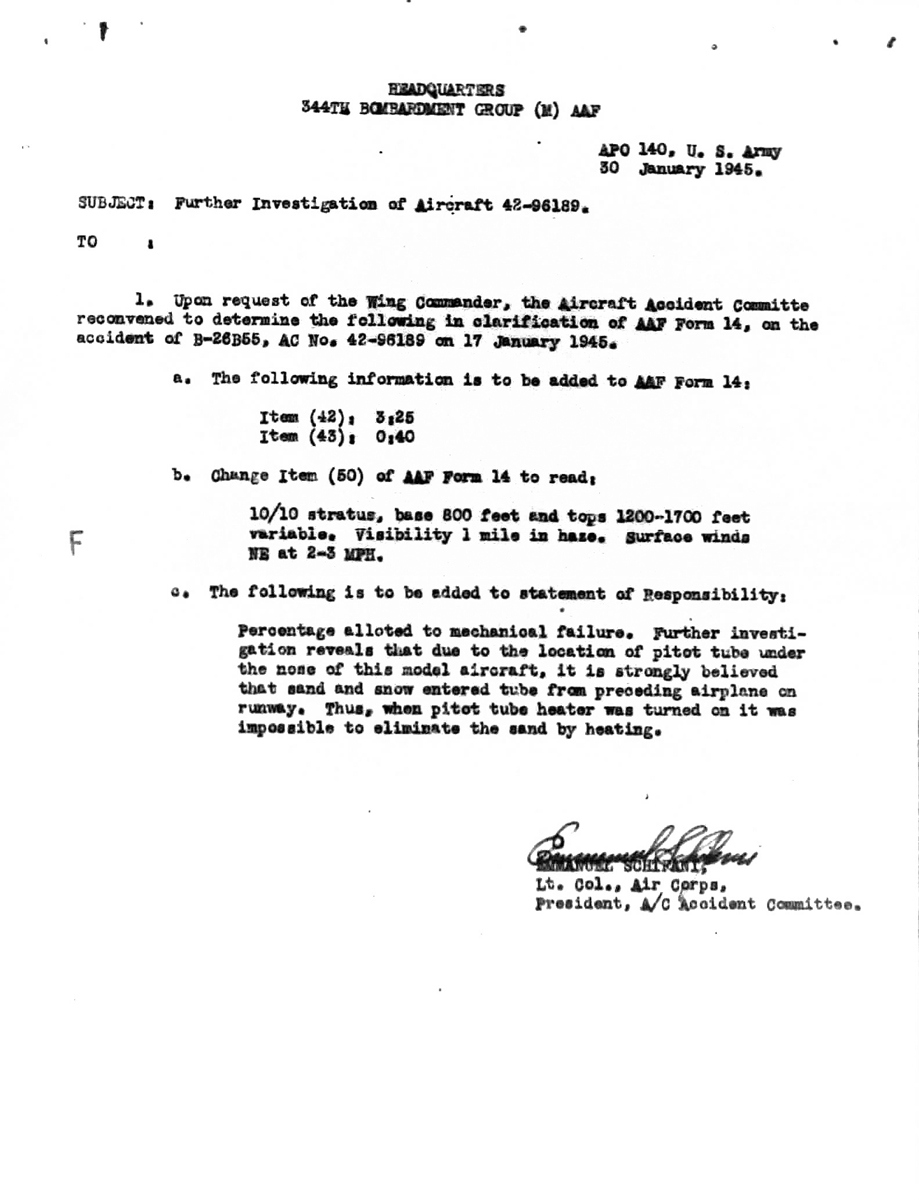

Our crew stayed together for much of our time in Europe, but I began to fly with other crews, occasionally as first pilot, but more often as copilot for a box or Group Leader. It was shortly after I began to fly with others that McSwain and Company had another close call. They were high-flight lead and during the takeoff roll, fully loaded, they could not reach takeoff speed. McSwain cut the throttle, but couldn’t stop the aircraft. They skidded off the runway buckling the nose gear and, after coming to rest in a snowbank, quickly evacuated the aircraft. Aside from being shaken and sustaining a few bruises, everyone got away safely.

Shortly after VE Day we had a chance to fly at low altitude over the German cities which had been targets of the Air Forces or were centers of Ground Forces engagements or both. The devastation was so extensive, we could to a degree empathize with the victims. However, at about this time we got first hand pictures and accounts of the death camps. Although we weren’t eye witnesses, the impact was horrific, one never forgotten.

By the time our crew had acquired enough “points” to be sent homeward just before the group moved to Schlessheim, Germany, as part of the occupation forces.

A few weeks after VE Day we were sent to Paris to await transportation to the USA. We were quartered in the Bois de Boulogne on the outskirts of Paris and, for a couple of weeks, enjoyed the champagne and City of Lights again.

Soon we boarded stripped railway boxcars for a trip to Le Havre. These cars appeared to be remnants of the 40 and 8’s of WWI notoriety. We didn’t mind this primitive transport or the crammed troop ship; we were on our way home.—

Lt. McSwain piloted several missions during the Battle of the Bulge (Ardennes 12/16/44 -1/16/45). Bad weather caused the cancellation of several missions. The airmen of the 344th were anxious to support the ground troops who were having a hard time due to cold, snowy, weather, desperate German troops, enemy artillery, and some poor strategic decisions by the upper echelons of command.

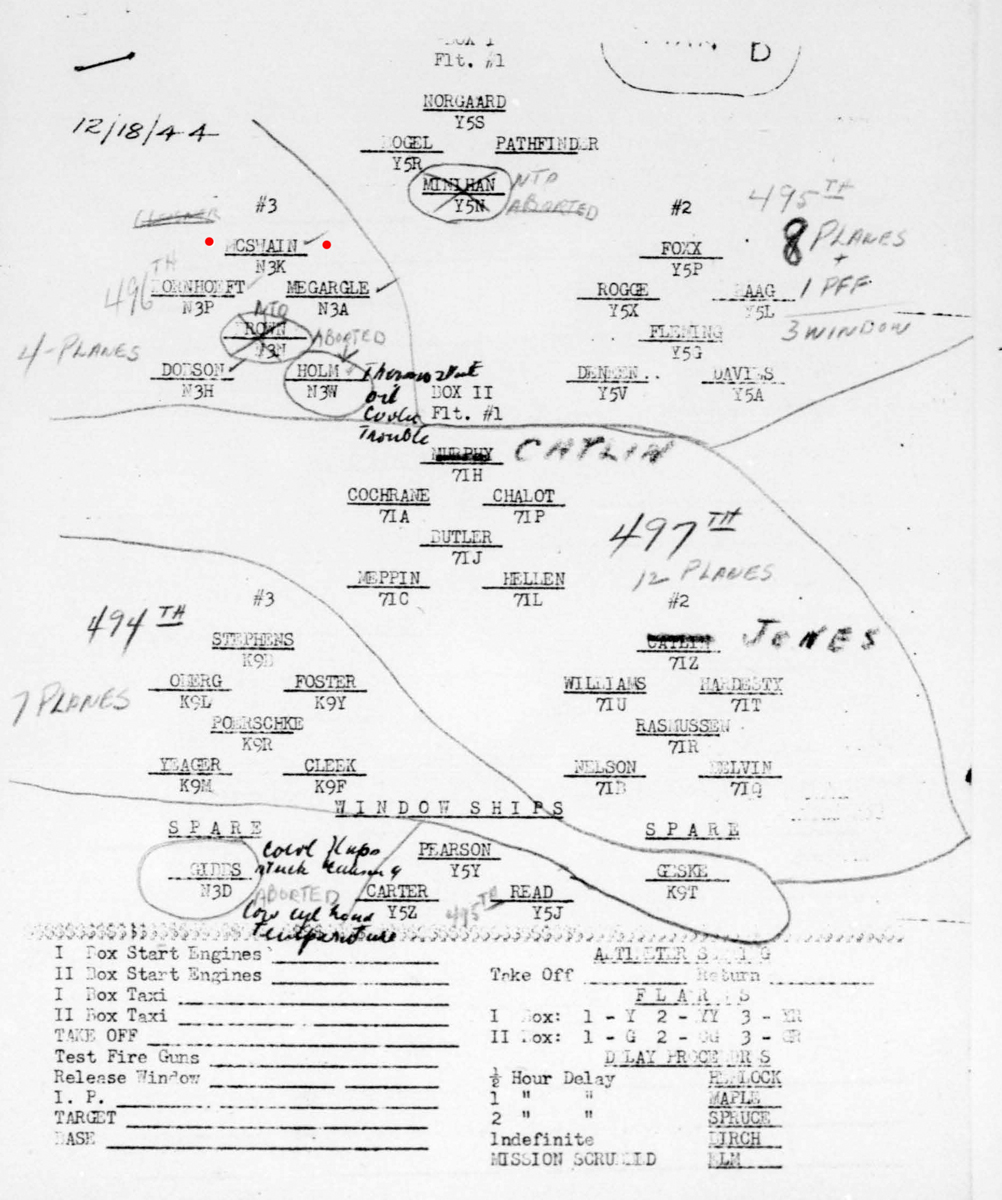

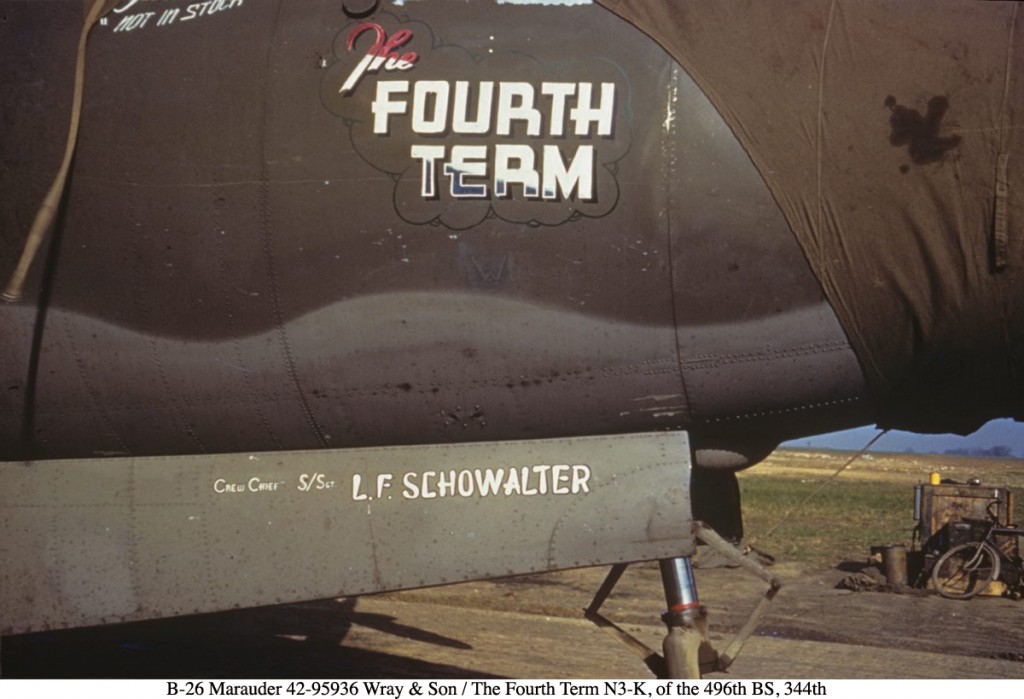

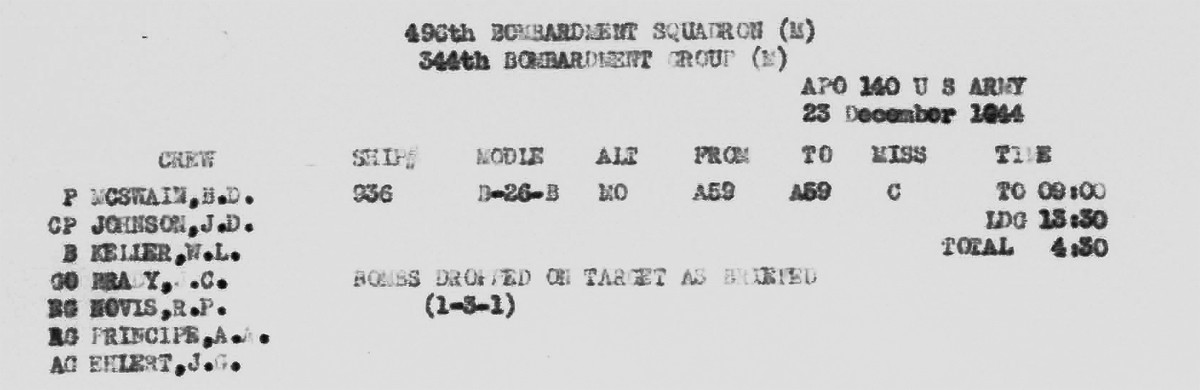

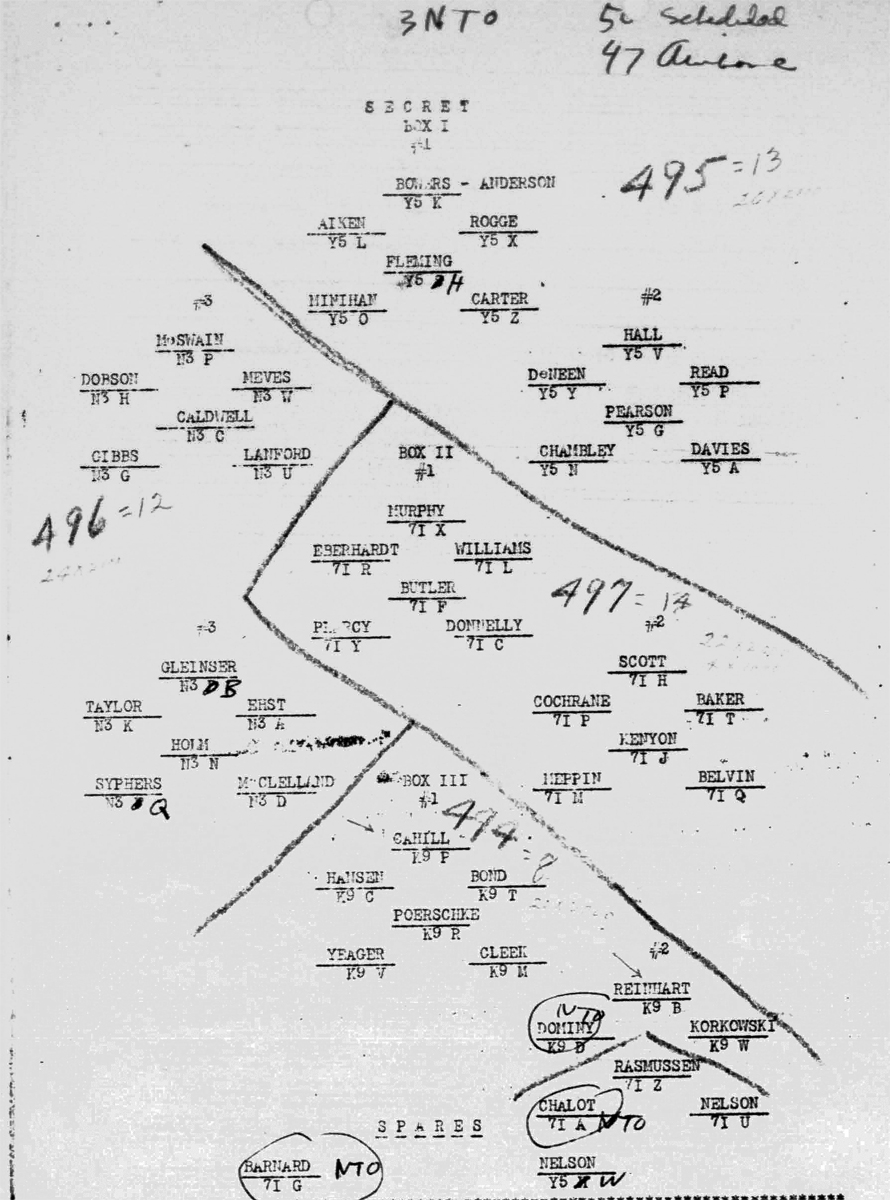

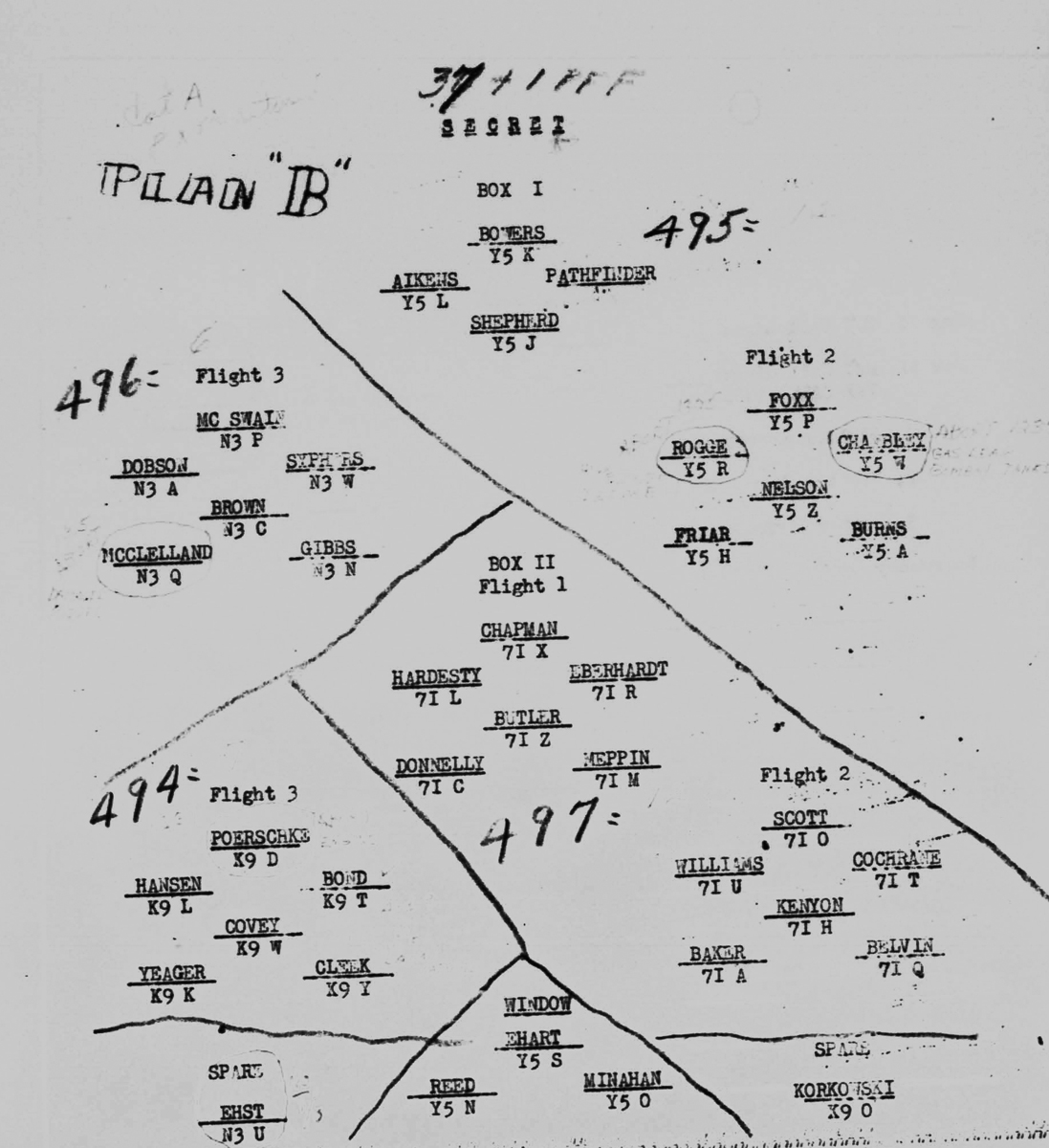

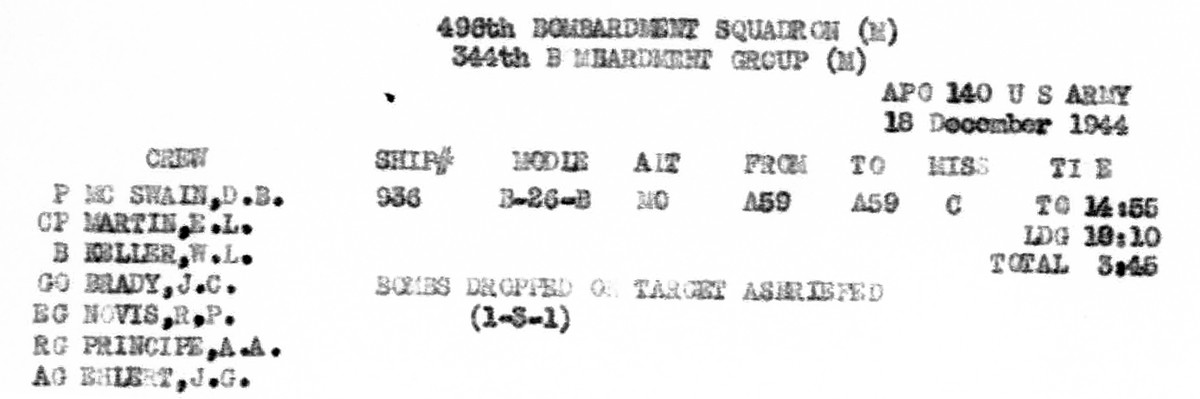

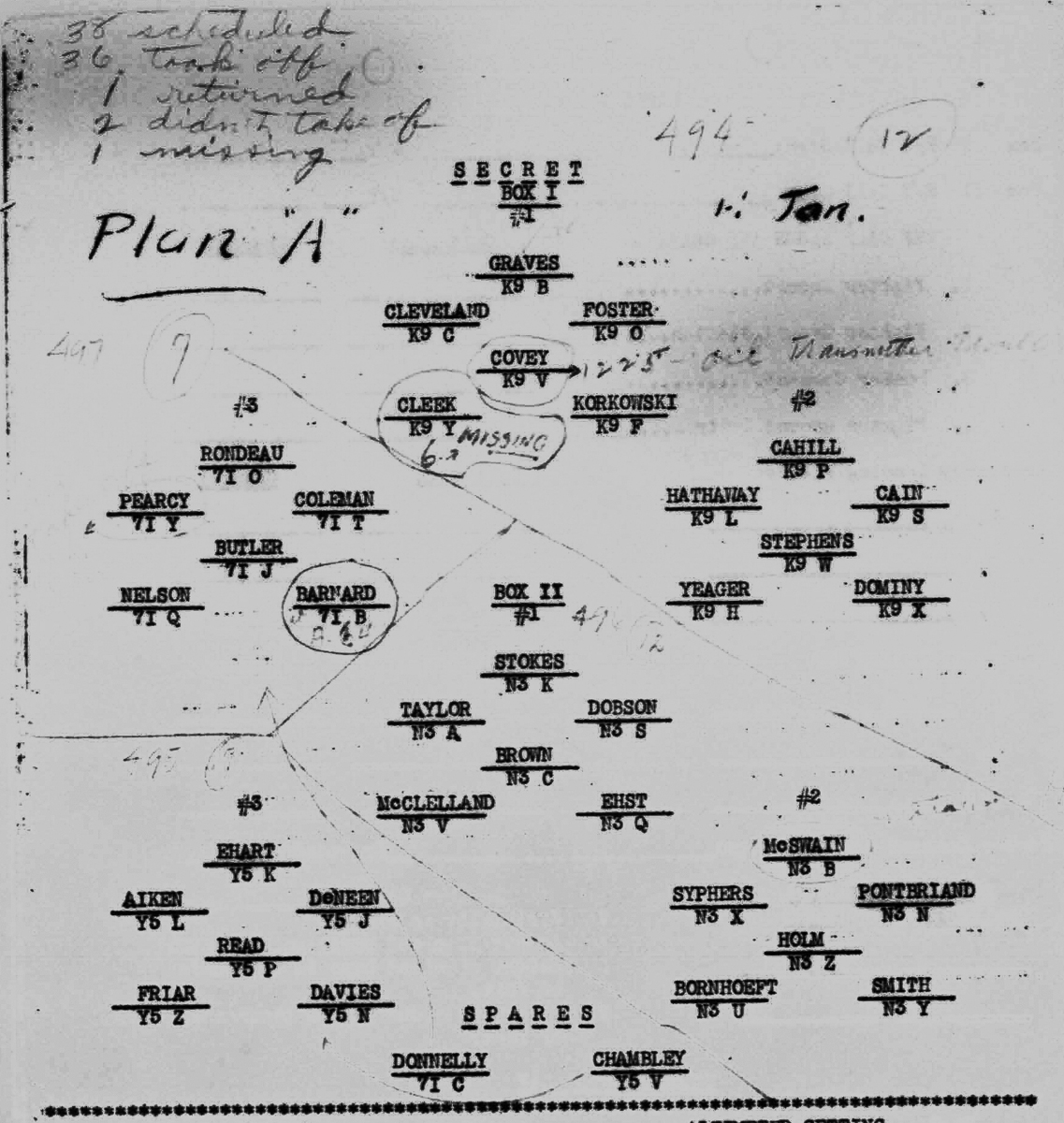

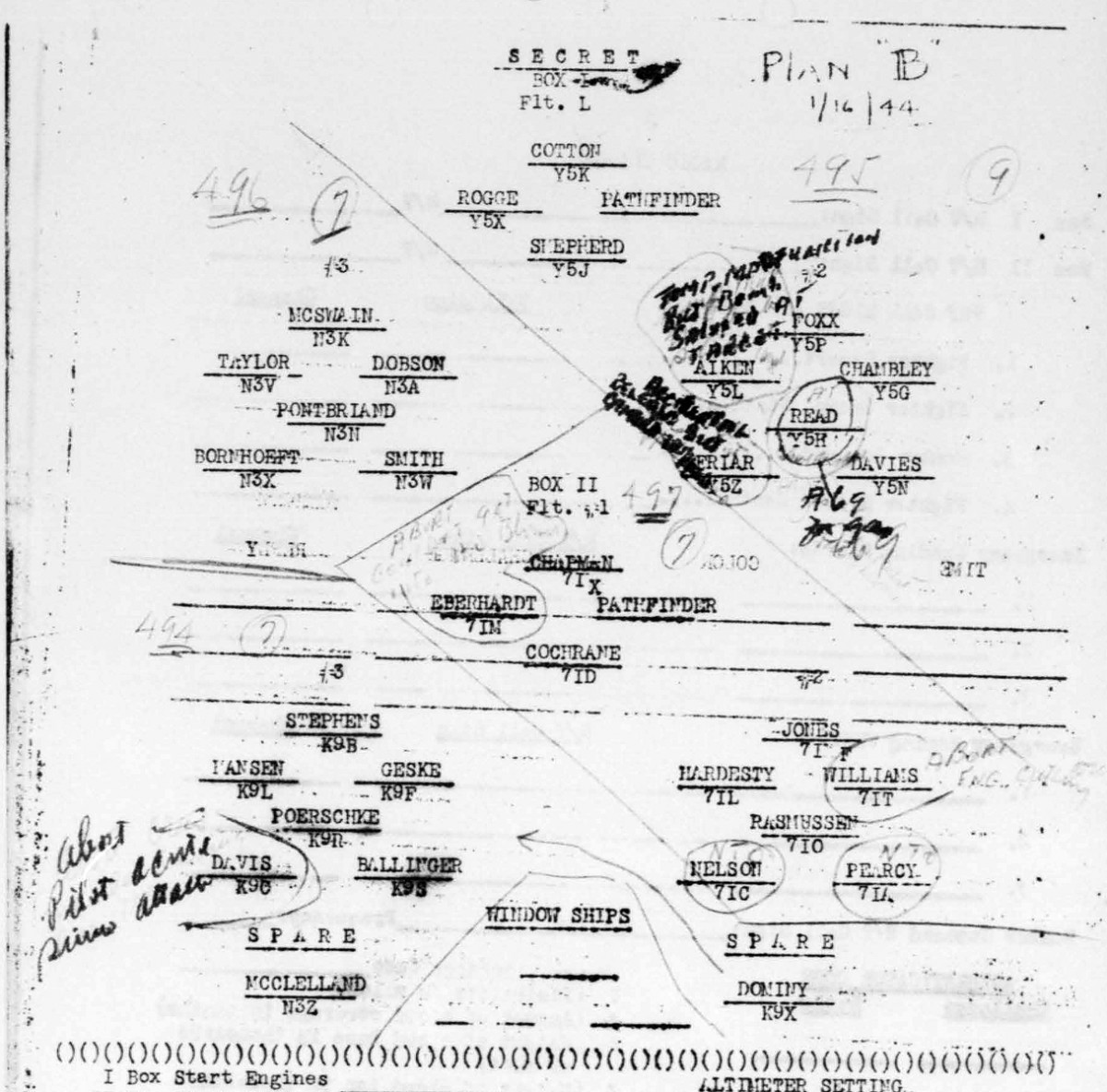

On 12/18/44, the 344th BG was finally able to get its’ bombers in the air. The mission was to bomb an enemy defended town at Herhahn. The formation diagram shows Lt. McSwain piloting the aircraft 42-95936 N3-K called “Wray & Son” or The Fourth Term.”

He is in the lead plane of the third flight of the the first box. The formation was led by a Pathfinder aircraft possibly using the top secret Oboe device for locating the target through clouds. McSwain’s crew included a Gee operator. Gee is another top secret targeting method perhaps to back-up the Pathfinder.

The loading list shows his crew to be; McSwain, pilot; Martin, Co-Pilot; Keller, Bombardier; Brady Gee (top secret nav. device) Operator; Novis Engineer Gunner; Principe, Radio Gunner; Emlert, Armorer Gunner.

The loading list shows his crew to be; McSwain, pilot; Martin, Co-Pilot; Keller, Bombardier; Brady Gee (top secret nav. device) Operator; Novis Engineer Gunner; Principe, Radio Gunner; Emlert, Armorer Gunner.

The bombs were successfully dropped as briefed. They took off from Cormeille-en-Vixon at 2:55 pm and returned there at 5:10 pm.

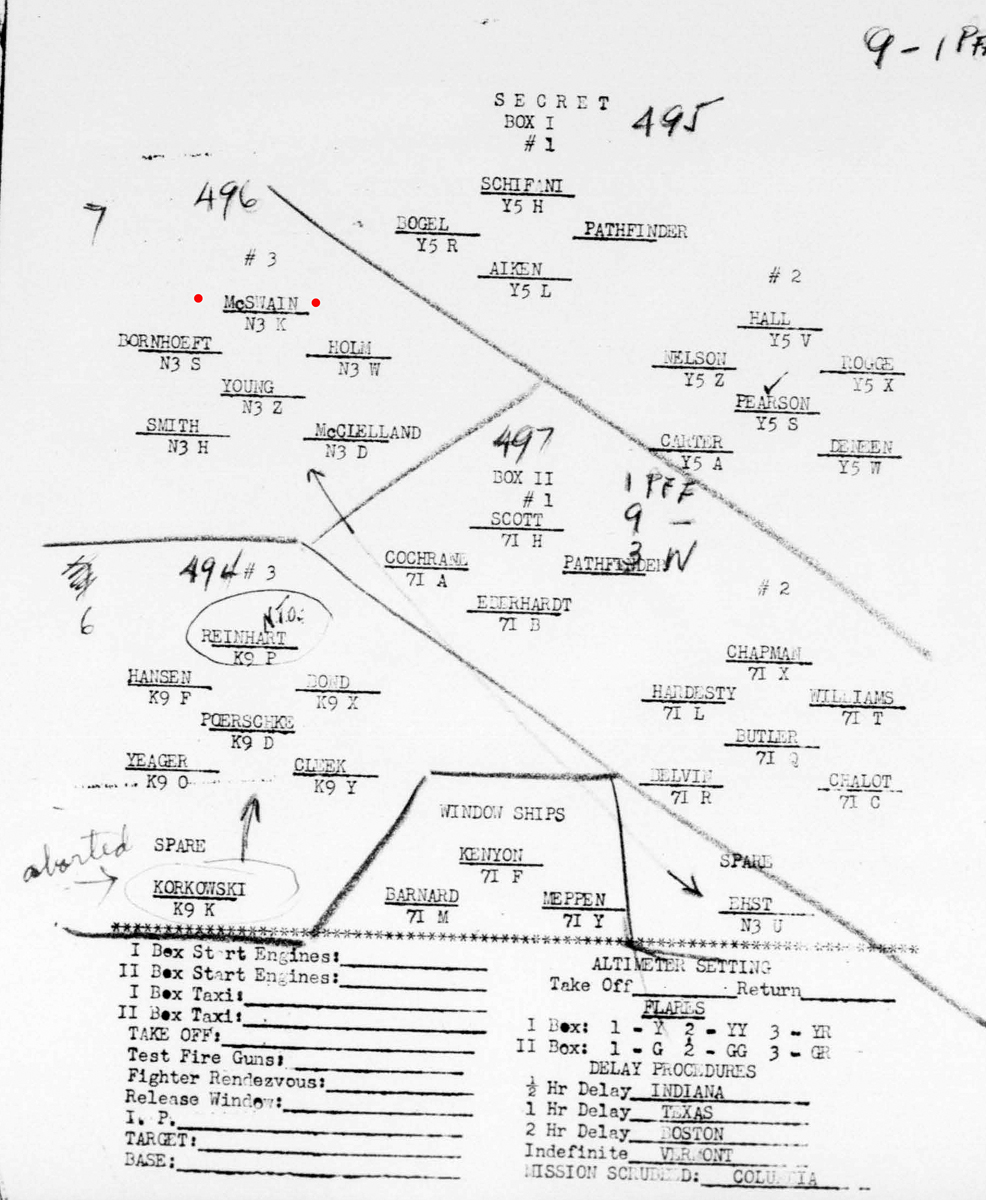

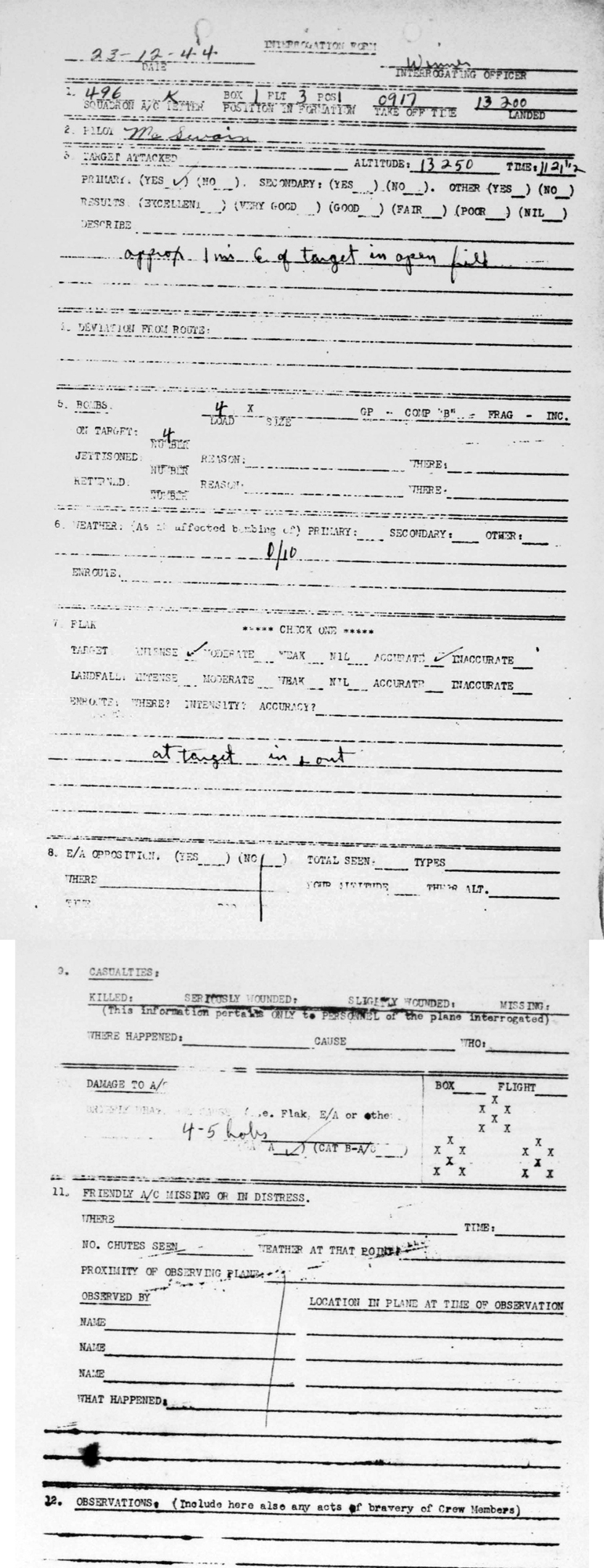

The next time they were able to fly to the Ardennes area was 12/23/44. The mission was to bomb an enemy defended area at Euskirchen. Bombing was done on Pathfinder. Lt. McSwain was again the lead plane of the third flight of the the first box. The plane was again 42-95936 N3-K called “Wray & Son” or The Fourth Term.”

Webmasters note: Carrozza flew with Aiken in 1-1-4 position that day.

The loading list shows his crew to be; McSwain, pilot; Johnson, Co-Pilot; Keller, Bombardier; Brady Gee (top secret nav. device) Operator; Novis Engineer Gunner; Principe, Radio Gunner; Ehlert, Armorer Gunner.

The bombs were successfully dropped as briefed. They took off from Cormeille-en-Vixon at 9:00 am and returned there at 1:30 pm.

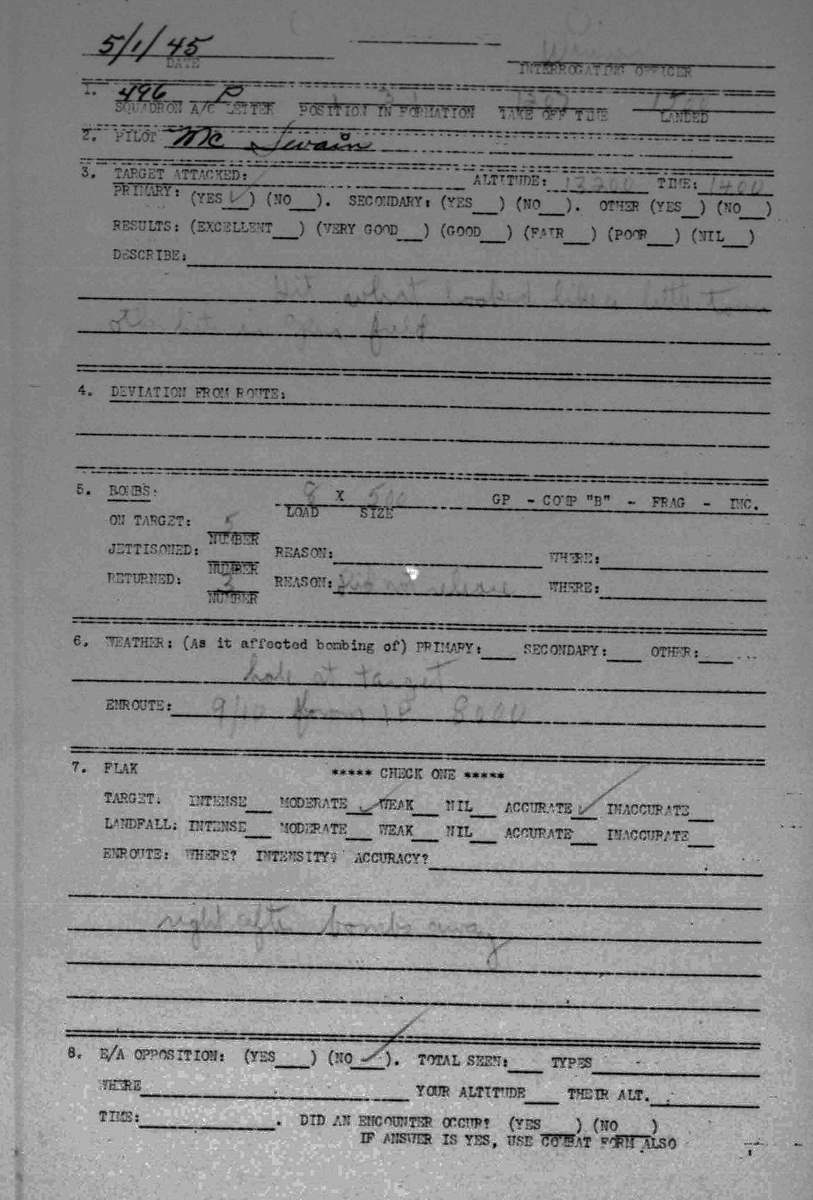

This Debriefing form was filled in by McSwain himself. Note the bombing took place at an altitude of 13,250 ft. He experienced flak at the “target, both in and out.” The bombs were dropped 11:21 am. The aircraft got 4-5 flak holes in it.

Records indicate that all 496th BG bombs fell outside a 1000 ft radius of the bridge. Intense flak at the target resulted in damage 6 of their 7 planes.

12/24- Did not fly

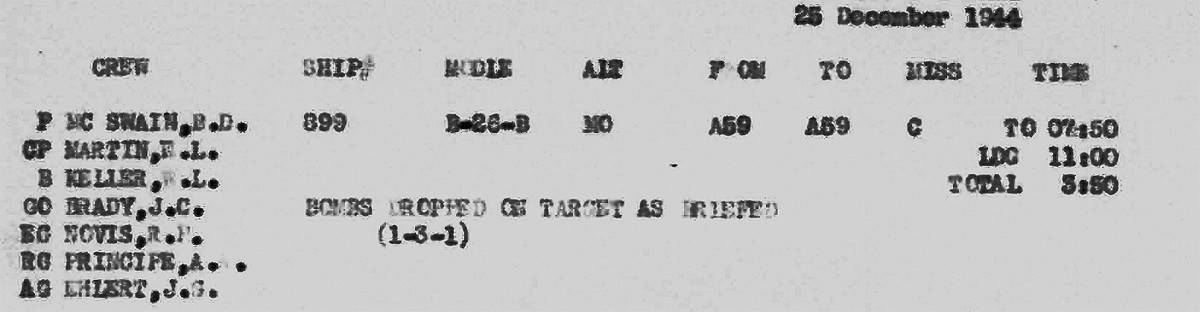

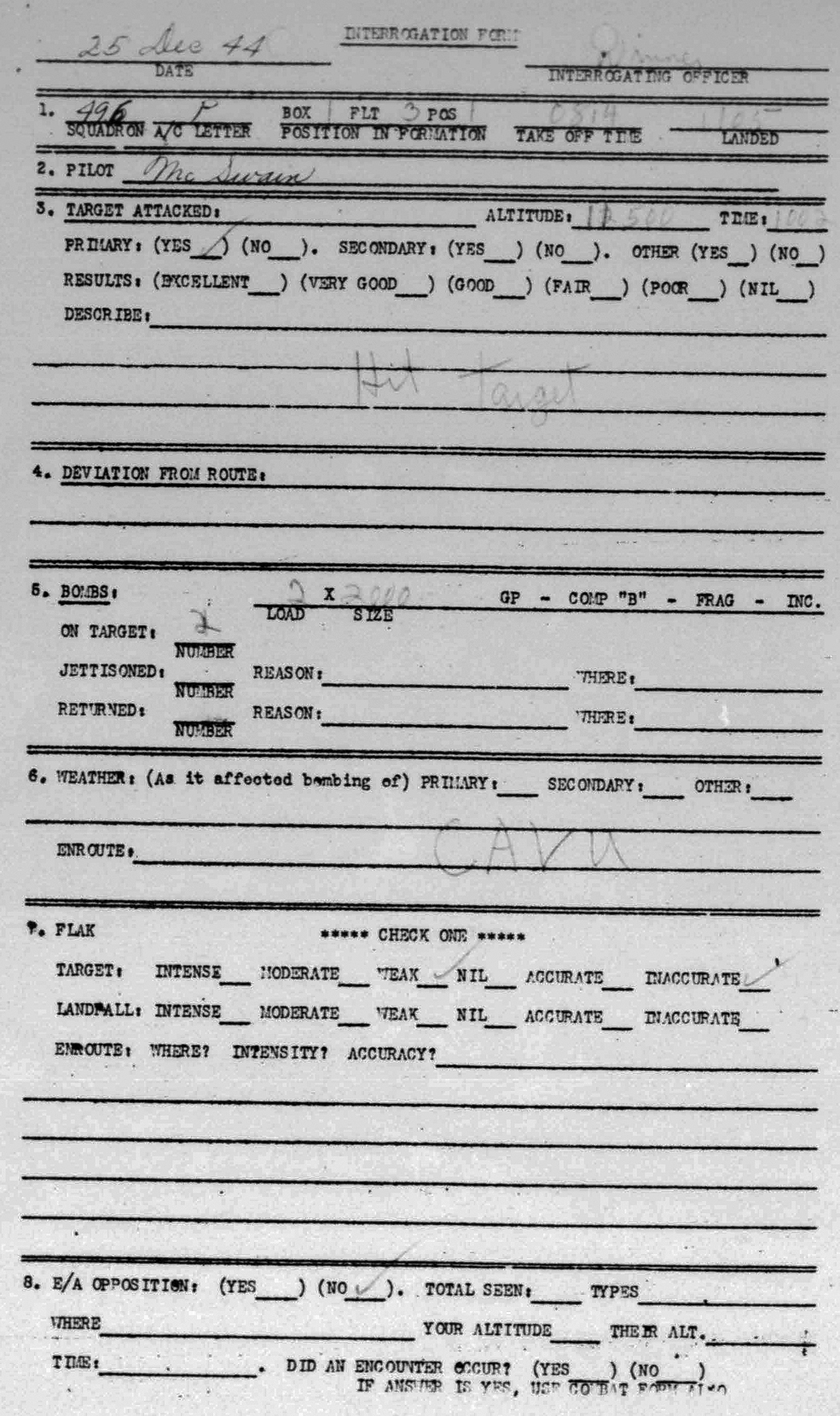

12/25- McSwain and crew flew 42-95899 “Maffrys Mottled Marauder” N3-P

On Christmas Day, the 496th squadron participated in two missions. The morning mission had as its target, the same bridge at Kons-Karthaus, where one rail was found standing. Our planes made up the third flight of the 2nd box. An excellent was scored by the 1st flight with possible direct hits on the western end of the bridge.

TARGET: RAILROAD BRIDGE

LOCATED: TRIER, GERMANY (Kons – Karthaus)

BOMB LOAD: 2 – 1000LB.

McSwain reports that he hit the target, bombing from 11.500 ft at 10:02 am. They faced weak, inaccurate flak and no enemy fighters.

12/25 mission 2 Did not fly

12/27 Did not fly

1/1 Did not fly

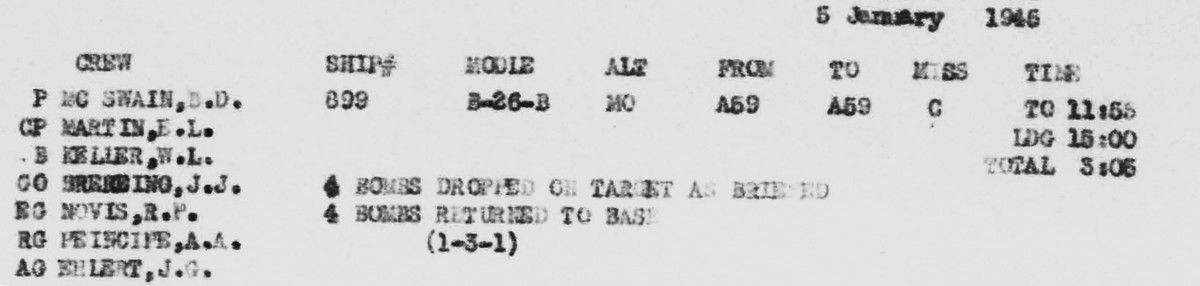

January 5, 1945

The objective of the mission (Houffalize Road Junction) was to destroy the enemy’s rail supply line in the salient and deprive his forward troops of the materials of war which they so badly needed. Bombing was done on Pathfinder lead with excellent results for the first box, of which our flight was a part. Moderate accurate flak was encountered at the target and turn off the target damaging four planes

TARGET: ROAD JUNCTION

LOCATED: HOUFFALIZE (10 MILES NORTH BASTOGNE)

BOMB LOAD: 8 – 500LB.

FLAK: INTENSE & ACCURATE

ESCORT: AREA COVER SPITFIRES

McSwain led the third flight of the 1st box in 42-95899 “Maffrys Mottled Marauder” N3-P

Lt. McSwain’s crew featured a different co-pilot (E.L. Martin and Gee operator (J.J. Brerbino (spelling?)). The plane took off at 11:55 am and landed at 3:00pm.

Lt. McSwain’s crew featured a different co-pilot (E.L. Martin and Gee operator (J.J. Brerbino (spelling?)). The plane took off at 11:55 am and landed at 3:00pm.

In the debriefing form, McSwain says they attacked the target at 2pm at an altitude of 13,200ft. A hole in the clouds appeared at the target. The bombardier was able to release 5 of the bombs. Three did not release. He faced moderate yet accurate flak right after bombing.

1/11- Did not fly

January 11, 1945-

Rinnthal—The target was a railroad embankment bridge which fronted an important link in the interdiction plan to separate the enemy battle fronts in the Sixth Army Group area from its source of supply. This mission proved to be the first visual of the month. Our squadron’s first flight scored a superior with probable hits on the bridge. The results of the second flight were unsatisfactory. No flak was encountered and all ships returned safely.

TARGET: RAILROAD ALONG MOUNTAINSIDE

LOCATED: RINTHAL, GERMANY (6 MILES WEST OF LANDAU)

BOMB LOAD: 2 – 2000LB.

DAMAGE: NONE

FLAK: ONE OR TWO BURSTS

ESCORT: P47 & P38

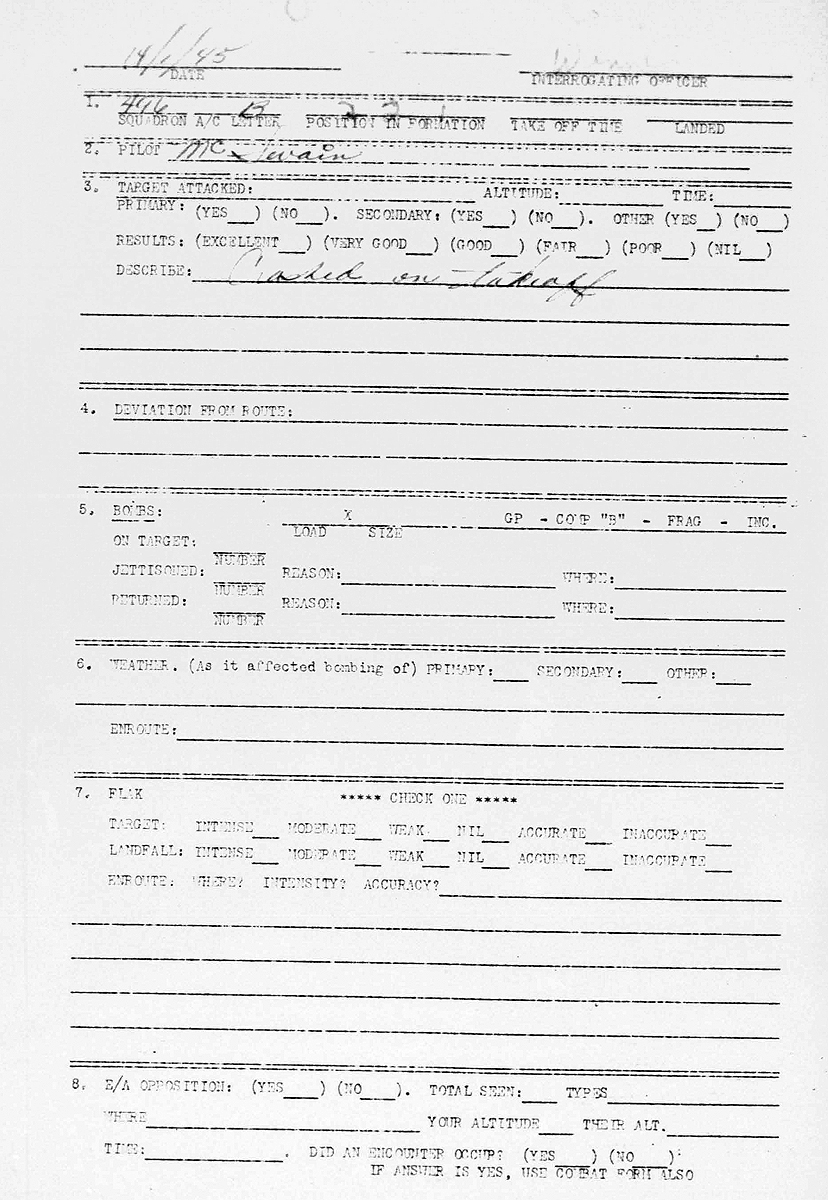

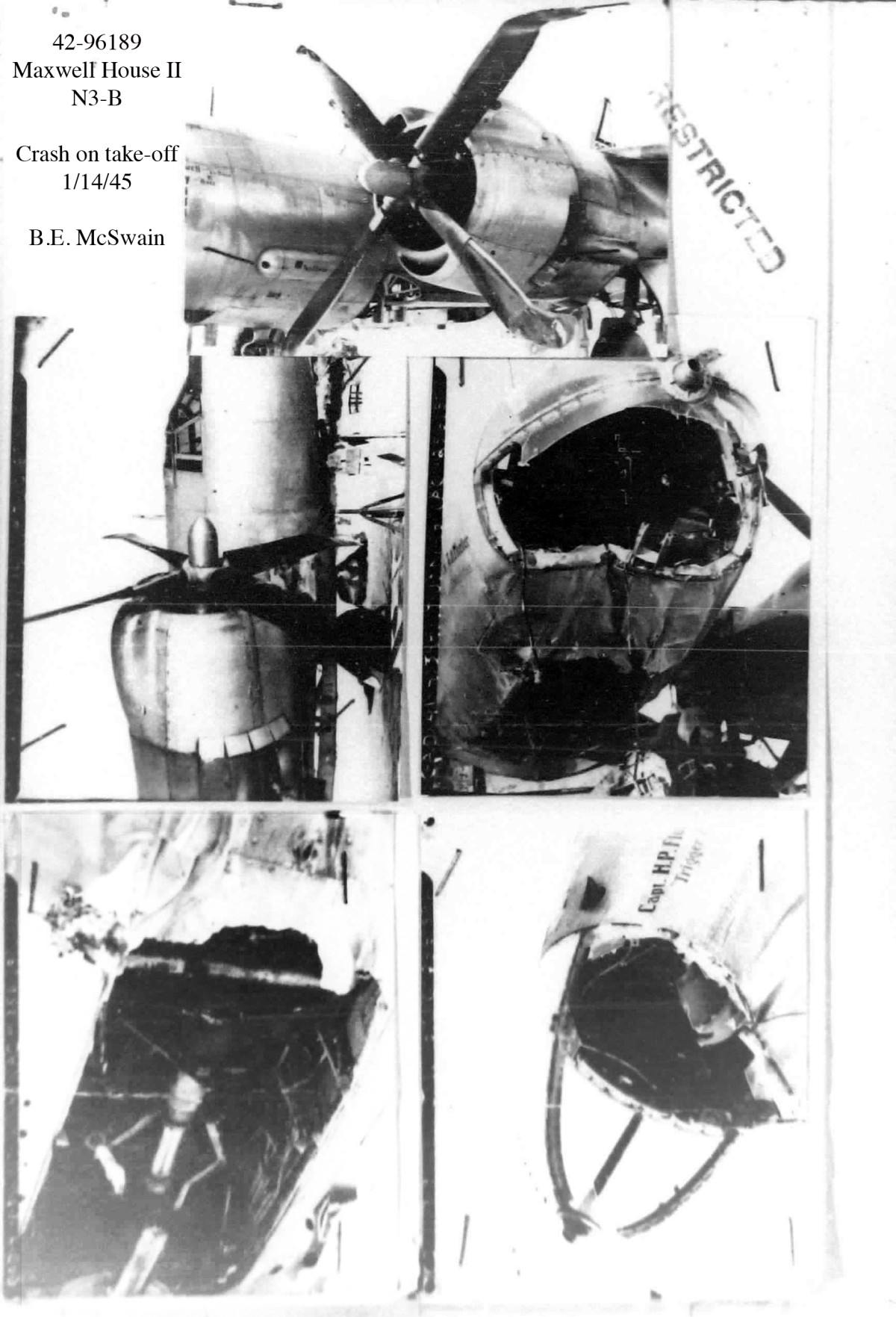

B.E. McSwain was supposed to lead the second flight in Box 2 flying N3-B 42-96189 “Maxwell House II. The plane crashed on take off. All hands were ok.

The following are documents regarding the crash incident:

January 16, 1945

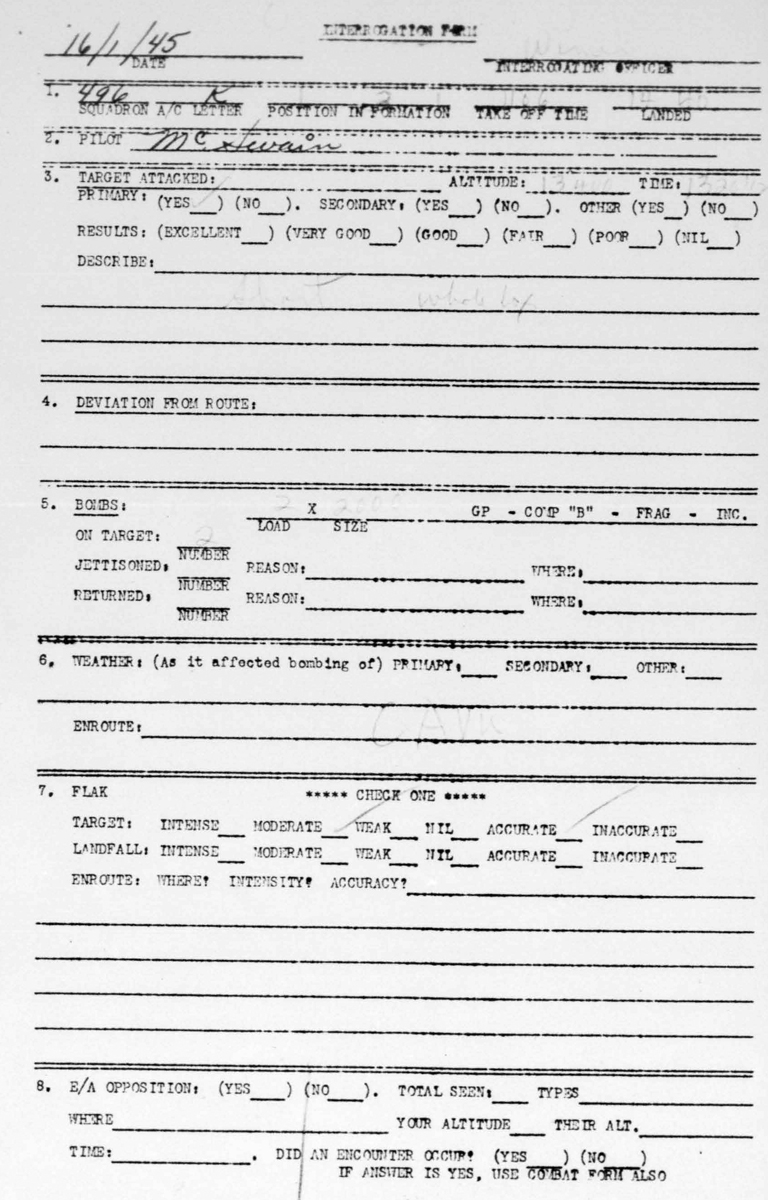

Bullay Railroad Bridge. An important railroad link across the Moselle River supplying the enemy troops in the Bulge area. The mission took off in Pathfinder formation, but bombed visually by boxes, through a break in the clouds over the target. The lead ship was caught in prop wash of a preceding group causing tumbling of the Gyro and making synchronization impossible. The result was a bad miss. Three of our ships were damaged by flak when they flew too close to Trier, However, all planes returned safely.

TARGET: RAILROAD BRIDGE

LOCATED: BULLAY, GERMANY

BOMB LOAD: 2 – 2000LB.

DAMAGE: ONE HOLE IN RIGHT ENGINE NACELLE

FLAK: MODERATE & ACCURATE

ESCORT: P47 & P38

REMARKS: P.F.F BUT BOMBED VISUAL

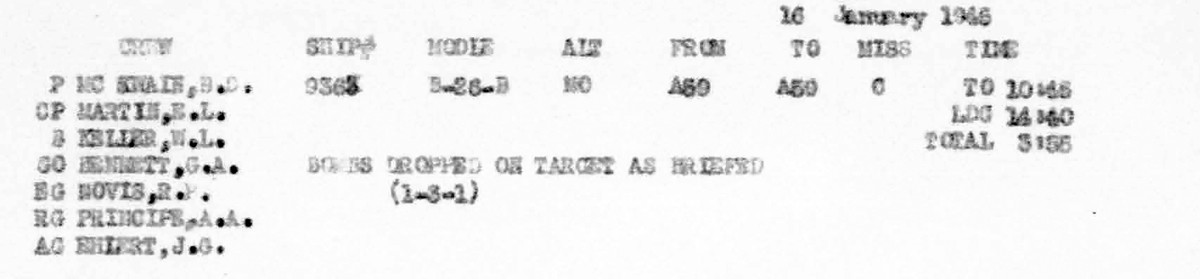

The formation diagram shows Lt. McSwain piloting the aircraft 42-95936 N3-K called “Wray & Son” or The Fourth Term.” McSwain lead the third flight of the first box. The formation was led by a Pathfinder aircraft possibly using the top secret Oboe device for locating the target through clouds. McSwain’s crew included a Gee operator, G.A. Bennett. Gee is another top secret targeting method perhaps to back-up the Pathfinder.

The formation diagram shows Lt. McSwain piloting the aircraft 42-95936 N3-K called “Wray & Son” or The Fourth Term.” McSwain lead the third flight of the first box. The formation was led by a Pathfinder aircraft possibly using the top secret Oboe device for locating the target through clouds. McSwain’s crew included a Gee operator, G.A. Bennett. Gee is another top secret targeting method perhaps to back-up the Pathfinder.

According to the loading list above, the bombs were dropped on target. The plane took off at 10:45 am and landed 2:40 pm

According to the loading list above, the bombs were dropped on target. The plane took off at 10:45 am and landed 2:40 pm

According to the debrief form above, McSwain dropped the bomb load of 2- 2000 lb. bombs at 1:20 pm from 13,400 ft. The flane experienced moderate and accurate flak and no enemy fighters.

According to the debrief form above, McSwain dropped the bomb load of 2- 2000 lb. bombs at 1:20 pm from 13,400 ft. The flane experienced moderate and accurate flak and no enemy fighters.

k