James K Dumas Tail Gunner

Cleburne Times-Review, Cleburne, TX

December 31, 2005

Ken Dumas, veteran of three wars, values friendships

By Larue Barnes/Guest columnist

New Year’s Eve reminds us of those who have meant the most to us in our lifetimes — where we were when we knew them — what was said and done.

If you visit with Ken Dumas in his Cleburne home, you sense quickly that he values friendships every day that he lives.

Dumas had a military career that spanned 32 years of active service. From the European Theater in the Army Air Corps in World War II, to service in Japan in the United States Air Force, to his tours in the U.S. Army in the Highlands and southern part of Vietnam, Dumas served our country with pride. From a tail gunner in World War II to an airplane and helicopter pilot with more than 17,000 flying hours, he faced the grim realities of war.

It’s difficult to get him to tell you about himself, because he wants to tell you how wonderful others have been to him during his lifetime. He still keeps in touch with his remaining fellow airmen from World War II.

On Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Ken Dumas was a junior in high school in Hillsboro, Texas.

He recalled: “I remember the sacrifices made at home. The women of the town rounded up their aluminum pans and took them down to the courthouse square and piled them up. That aluminum was needed to make airplanes.

“And I remember all the boys wanting to go to the service. Some of us weren’t old enough at that time. Most of the boys wanted to get into the Army Air Corps — it seemed like a glamorous thing. I can remember hearing them talk before they went for physicals. It was the rumor of the day that if you were going in for a flight physical to see if you could get into the aviation program, you’d eat carrots so that would improve your eyesight. If you were underweight, you would eat bananas. If you were short, you did different stretching exercises to try to grow taller.”

He grinned and added: “I remember trying that one, myself. On Dec. 2, 1942, when I was still 16, I joined the military. There were four of us from Hillsboro who went: Billy Boatright, Richard King and Aubrey Graves and me. I went to basic training at Camp Wolters in Mineral Wells. From there I was sent to Sioux Falls, S.D., to a radio school and on to Denver, Colo., to armament school. After training in Florida, I was sent to Shreveport, La., for training with my overseas unit.

“When we got ready to go overseas we went to Savannah, Ga., to pick up a new airplane. When we got there, there were no airplanes so they put us on a train to Brooklyn, N.Y.”

Dumas’ memories of his trip overseas on the Queen Elizabeth were those of massive overcrowding.

“They said there were 15,000 troops aboard,” he said. “We ate twice a day, but there was no place to sit down so you stood up to eat. If the military police caught you without your life vest on, they would have you take your right boot off and they would keep it until you put your life jacket on and came back. The problem was, they would go to get their boot and they couldn’t find the MP.

“So before we landed at Glasgow, Scotland, they announced over the loud speakers that for everybody that was missing a boot to go to the aft deck and find one their size.”

Dumas joined the 344th bomb group in Stratford, England, and moved to France.

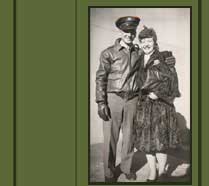

“It was common in World War II for crews to choose some movie star as their pin-up girl,” he said. “Sometimes they even had her picture painted on the airplane. My whole crew adopted Marchieta Harrington, my sweetheart, as their pin-up girl. To this day, I have never flown without that particular picture in my wallet”

He showed me Marchieta’s picture in her Hillsboro High School yearbook, where she was pictured as a yell leader. He said proudly, “She was very popular. I was so grateful that she fell in love with me. We wrote to each other faithfully all during the war.

“I flew 37 missions against Germany. Flak was our biggest problem. I was 17 years old — soon turned 18. I had no fear. You could smell flak [antiaircraft shells shot from the ground by the enemy that exploded at different levels of altitude].”

Dumas kept a record of all the missions flown by the Silver Streaks — destroying ball bearing factories, railroad bridges, ordinance and supply depots, airfields and marshaling yards all across Germany.

“I was tail gunner on a B-26,” he said. “At first I thought flak was kind of pretty until it started rattling against our plane. When we went through flak I knew there weren’t going to be any enemy fighters coming at us through that, so I often left my tail gunner position and grabbed a hand camera and shot pictures down through the bomb bay.

“I got good shots of bombs being released. Once when I was doing that, I saw this flash. I had taken a photo of one of our planes that had been hit and was going down.

“My worst mission was the one where 16 or our airplanes were shot down out of the 36 in formation. Afterwards, it was my job to gather up the possessions of some of the airmen who had been shot down. I got all the military stuff together and then looked at some of their personal belongings and commented that they weren’t worth sending home.

“An older airman, John J. Beddingfield, someone I greatly admired and who taught me how to grow up quickly, said, ‘Let me tell you something. It may not mean anything to you, but it means the whole world to their family.’”

After one bombing mission, Dumas’ crew was told they were running low on gas. They were over Belgium and made an emergency landing.

“We landed in Peer, Belgium,” he said. “Three of us stayed several days with a wonderful family there, up in the attic over Jeff Schrijvers’ pastry and baking shop. We got to know them, helping him bake. Mrs. Schrijvers kept a detailed record of everybody who stayed there. It took us several days to contact our command post to let them know we were alive and safe. We still have the Missing in Action letter the post sent to our families just before we made contact with them.

“In 1983, the Schrijverses’ grandson, Peter, mailed a letter to me at my dad’s address in Hillsboro. My dad had died in 1965, but the postman went to school with us and sent the letter to my mother-in-law. She mailed it to us in Denver.

“Peter came over here in 1985. I flew him to Baton Rouge, where he was enrolling in school. Since then he has earned his doctorate and speaks and writes five languages. He majored in American history and dedicated a book of his to me and the two others who stayed with the family. His father was only 6 years old at the time, but remembered all about our days there.”

Schrijvers wrote in the preface of “The Crash of Ruin,” published by MacMillan Press in 1998: “The first seeds of this book were sown during a stay in the American Deep South in 1985. It was my first trip to the US and the purpose of my visit was the long-awaited reunion with the members of a B-26 crew who had stayed with my grandparents at Peer, Belgium, after an emergency landing early in 1945. For five weeks my hosts treated me with that wonderful southern hospitality and needless to say, I had the time of my life.

“It was only when my American friends visited Belgium a few years later that it dawned on me how much World War II had done to distort their image of Europe … they were veterans who had seen Europe in ruins.”

The author said he kept wondering to what extent Dumas and the others were surprised by European progress. He decided to turn the GIs’ perception of Europe during World War II into the subject of his doctoral research. He wanted to find out how their mental image had been distorted by the exceptional conditions of the war.

Dumas said: “We were in Belgium when the war was over. What we saw then is what we remembered. You came home on points: each month in the company, each mission, decorations, etc. We were at a camp in Le Havre, France, waiting to get on ships to come home. The camps were named for cigarettes — Lucky Strike, Chesterfield, Camels, etc. While we were waiting we could go out of camp as long as we came back within three days to see if our ship had come. Beddingfield’s father had been in that area during World War I, and he wanted to explore a little. He had a relative in the motor pool who gave us Jeep parts. We built a Jeep for ourselves [to] be able to find the exact places he wanted to see. The problem was, Beddingfield missed his ship and had to wait two months for another one.”

Only one of Dumas’ crew of six in the 495th bomb squadron of the 344th bomb group of the 9th Air Force has passed away.

“In 1991, we had a big 344th bomb group reunion in Dayton, Ohio. I’ve worked really hard to keep all of us in touch and it has paid off,” he said.

Retiring in 1984, after rising in rank from private to Chief Warrant Officer 4, with an amazing array of medals, including the Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross and two Bronze Star medals, 22 air medals the Army Commendation Medal and Master Aviator Badge, Dumas was honored as an aviator with more than 14,000 hours of accident-free flying time. Rated as an Army aviator Jan. 14, 1956, Dumas accumulated more flying time than any other active duty aviator.

Dumas said he was in and out of the service, spending time in ag school in Hillsboro for one stint, and for 10 years as an engineer for the Santa Fe Railroad. But he kept returning to flying, admitting that nothing gave him as much personal satisfaction in the air as crop dusting.

He said he got into crop dusting in the late 1950s, working in Hill and Johnson counties for area ranchers and farmers. Back then, the pilot had to be resourceful and adapt his plane to carry the tank of chemicals effectively, he said.

“I started off with Don Graves, now of Navasota, flying his plane, which was designed as a mountain airplane — a 150 horsepower side-by-side with an open cockpit. I took the right seat out and installed a fiberglass hopper to hold liquids.

“I knew it was a hazardous career, so I went to Texas A&M; for a short course and served as an apprentice on the ground before he began crop dusting as a pilot.”

The biggest danger for the low-flying pilot involved electric and telephone wires.

“You were flying low, so you either had to fly under or over them. In an unusual emergency, if you couldn’t do either, you had wire cutters with saw teeth that would cut telephone wires. If that happened, then you reported it and paid for the repair.”

In 2002, Texas passed a law allowing veterans of World War II to receive their high school diplomas if they dropped out to go to war. Dumas was intrigued with that.

“I had gotten some college hours already, but I wanted my diploma from my high school very much. Seven of us applied for that in Hillsboro. They told me I could go to the office and get it right then, have them mail it to me, or actually be a part of the graduation ceremony. I wanted to actually graduate.”

Then a surprise was planned for Dumas by a Cleburne friend, Gary Lillard.

Dumas said: “Gary and I are friends and work together restoring antique cars. He knew about my upcoming graduation from HHS and called my wife to find out if I had a high school ring. I didn’t, so he found out my ring size and went to Zales jewelers. They researched and found out what a 1942 HHS ring looked like and made me one.

“Marchieta took me out to the mall. I thought we were meeting friends out there to eat. It was such a great surprise when I was presented the ring by Jerry Webber. Zales gave the ring to me at no cost to show their appreciation for what I had done in World War II.”

Marchieta and Ken Dumas are members of First Baptist Church in Cleburne. He has served as Worshipful Master of Cleburne Masonic Lodge 315. They celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary before Christmas. Their children, Pat Dumas of Lucas, Texas, and Penny Venglar of Port Orchard, Wash., came and visited a week. The house was filled with five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Friends from all over the United States sent their congratulations, and many came to visit.

His wife, daughter and granddaughter had listened intently as he had told me these things. No one had moved much, or interrupted his train of thought. Marchieta was able to finish a quote once when he had paused emotionally.

When he finished, they all wiped away tears. I thought of the young teenager, behind a machine gun — a glassed-in target in the tail gunnery of a B-26 — naively watching for flak and for enemy planes.

He showed me the photograph again that he had taken through the bomb bay doors when he had unknowingly captured the last few moments of an American pilot’s life.

He looked down. “Somehow, even after all these years, I really needed to pay my respects at his grave. I searched in the Netherlands until I found it.”

Larue Barnes may be reached at laruebarnes@yahoo.com. Larue Barnes’ daily devotionals may be read in the current winter edition of Open Windows magazine.