By the time James Gatlin was 23, he was the only surviving member of his family.

The Andrew Jackson grad’s only brother died when James was eight years old of complications from an apendectomy.

His mother followed three years later after a cerebral hemorrage.

In 1943, while James was training to be an Army Air Corps pilot, his father died in a car crash in Fernandina.

“He was no stranger to heartache,” said Gatlin’s cousin Connie Howard. “But he was a very loving and compassionate person.”

Howard, 11 years younger than Gatlin, found this out personally after she lost a sister as a child.

“He would come by and see my mother and talk with me, to check on me and make sure I was OK,” Howard, who was nine when her sister died in 1939, said. “After he joined the Army in January, 1941, he would write to me and tell me all about what was going on.

“I was just looking over the letters this morning.”

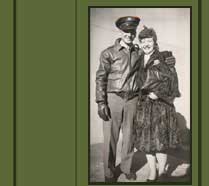

Howard said she was crazy about her good-looking older cousin with the dark hair and nice smile.

Gatlin and Howard’s father, a World War I veteran, were also very close, Howard said. Her father had been in some of the same locations during the Great War that Gatlin was seeing 27 years later.

“In one of James’ letters, the last one from Dec. 11, 1944, he had completed 20 missions and wrote, ‘Tell Uncle Wade it is nothing like I thought it would be,” Howard said.

Twelve days after he wrote that letter, Gatlin sat in the pilot’s seat of the B-26 Marauder nicknamed the “Silver Dollar” looking at thick, low clouds across the French landscape that cut visibility to two to three miles.

Not ideal flying weather by any stretch, but it would have to do.

This day, Dec. 23, 1944, was the first day allied bomber crews would be able to operate since the beginning of Hitler’s last major offensive, now known as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

U.S. Army soldiers had been thrown back by a massive, last-ditch push by the Nazi assault. Thousands were dead and other units, like elements of the 101st Airborne at Bastogne, were cutoff and totally surrounded by the German onslaught.

To make matters worse, the weather, freezing and cloaked in cloud cover, had kept the superior allied air units grounded — unable to relieve their frozen and exhausted comrades on the ground.

Today would be the day.

Gatlin and the rest of the 391st Bomb Group would fly to Ahrweiler, Germany and bomb a railway viaduct upon which the Germans were rushing reinforcements to their advancing Panzers and soldiers.

The American bombers took off from the French airfield about 1030 and reached their target about noon.

“The mission was designed as a Pathfinder task, but the formations met flak in unexpected places along the route, and the Pathfinder planes were knocked out of the lead position, filling in farther back in the formations,” wrote Lt. Hugh Walker, another pilot with the 391st. “Visibility was not good in the target area, making it necessary for both boxes to make two runs over the target.

“They were engaged by intense heavy flak fire on the second run, but it suddenly ceased with a red-colored burst, and enemy fighters dove in to attack.”

The Army Air Corps estimated that between 50 and 75 German fighters engulphed the U.S. bomber formations. In Gatlin’s unit, 16 of 30 bombers would not return to their base in France — the unit’s most casualties in a single mission since the war began.

“After bombs away I moved aft to the navigator’s compartment to operate the navigation equipment,” wrote Lt. John Adair, the Silver Dollar’s navigator. “I had just set my equipment on the navigator’s table when we were hit in the bomb bay by fighters.

“After I picked myself up, I opened the bomb bay door to check the damage and I found the bombay to be completely on fire.”

1st. Lt. John Garside, flying the lead plane on the mission said the fighters attacked just after bombs were dropped.

“The fighters attacked in waves of 15 to 20 at the time,” Garside wrote in his official report.

Adair took off his flack jacket, donned his parachute and moved toward the cockpit to tell the pilots of the damage.

“I hesitated for a moment to they if they were ready to jump,” Adair said. “Lt. Biezis [the co-pilot] was out of his seat and waiting for me to go.

“Lt. Gatlin was flying the plane with his left hand and ringing the alarm bell with his right hand, still in the pilot’s seat.”

Garside said other planes were going down all around him. Then he spotted the Silver Dollar “with the left engine on fire and the right engine feathered.”

“I did not see any chutes leave the aircraft, but his position denoted that he was bailing out his crew,” Garside said.

One month later, Gatlin’s aunt who lived on Gregory Place off North Main Street was notified of his disappearance. A short notice ran in the January 23, 1945 edition of the Florida Times-Union.

Though Gatlin’s remains weren’t found, his status was changed to killed in action after one year per Department of War policy at the time.

However, at the end of the war, Lt. Adair was liberated from a German prisoner of war camp and was able to provide his testimony.

He felt sure he wasn’t the only one to bail out.

It turns out, two other men did bail out.

In 1950, an investigation revealed that German documents showed that Staff Sgt. Milton Cowart and Staff Sgt. William Weissker also made it out of the plane.

Though the German authorities said Cowart was found dead with a bullet wound to the chest and Weissker died of injuries from the fall.

Adair asserted his opinion that Germans killed the men after they bailed out of the Silver Dollar, but he never saw any of his fellow crewmembers after he jumped from the plane. He lived for at least 40 more years not knowing his buddies’ fates.

Then a letter came from the Army dated 1985 listing the burial places and status of his comrades.

“You were the only one fortunate enough to survive,” the letter said. “I hope these two documents provide the information you are seeking.”

The documents still showed Gatlin, his co-pilot Lt. Biezis and Staff Sgt. Joe Sanchez as killed in action, but missing.

In 1999, a group of German researchers notified U.S. authorities they had found a crash site and remains.

Once the technology became viable, the U.S. Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office requested DNA samples from Howard, who was by that time the only living close relative of Gatlin, and a second-cousin.

“Mine came back as a perfect match,” she said.

The office began making preparations to have Gatlin’s remains returned to Florida.

Howard was the only person there with a living memory of James Gatlin when soldiers removed the flag-draped coffin from the plane.

“You talk about flashbacks, I was 13 when his dad died and James came home from the service,” Howard said. “He was so handsome, of course we all worshipped him anyways.

“When they brought that casket out of the belly of that plane over in Tampa,” she paused to gain her composure, “I was very emotional because I was the only one left who knew him.”

It’s been a long journey from December, 1944 to the cemetery in Bushnell where Gatlin’s remains were laid to rest on Jan. 30. After all other living relatives passed away, Connie Howard had to carry on the family’s pursuit to find Gatlin’s remains.

“It is nice to know he’s finally home,” Howard said. “I’ve been trying to find him since … well, I never stopped searching for him.”