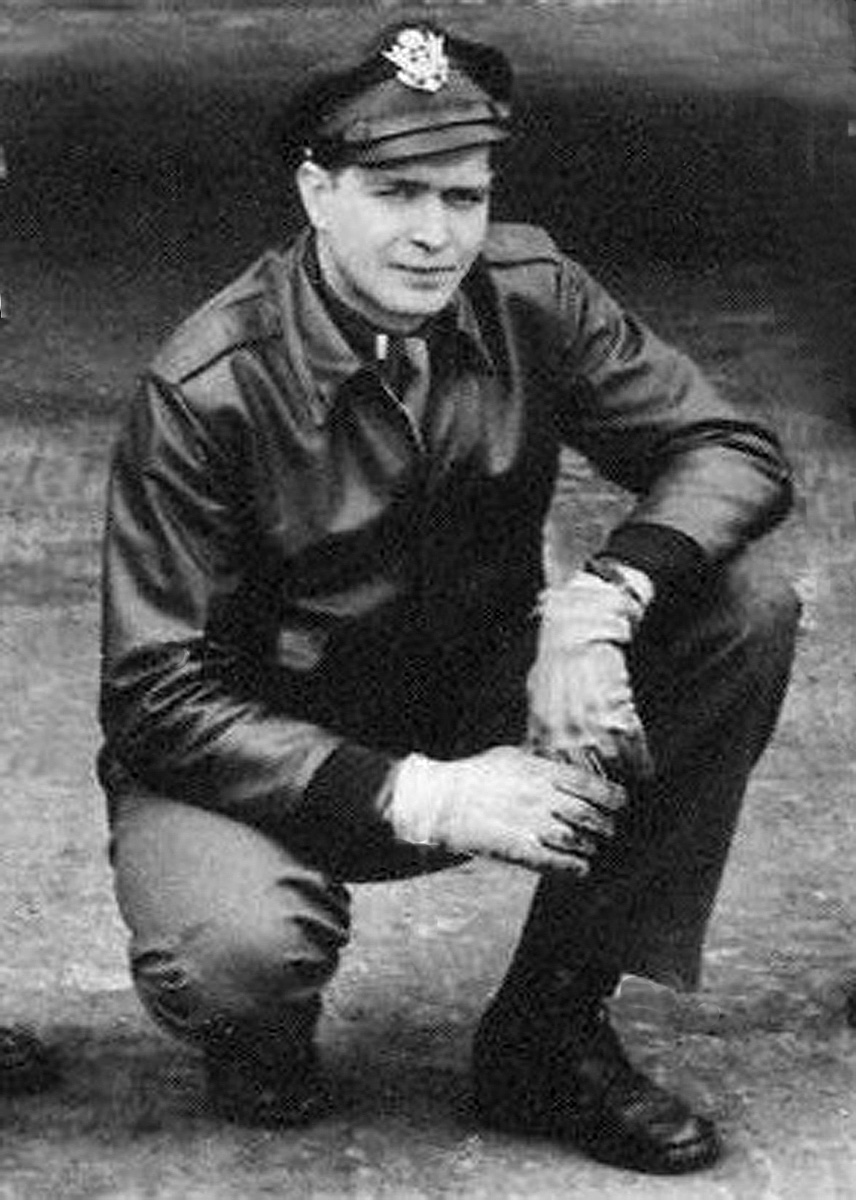

1st Lt. Glenn R. Young 344th BG 497 BS

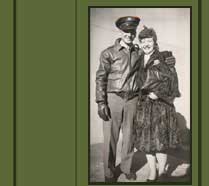

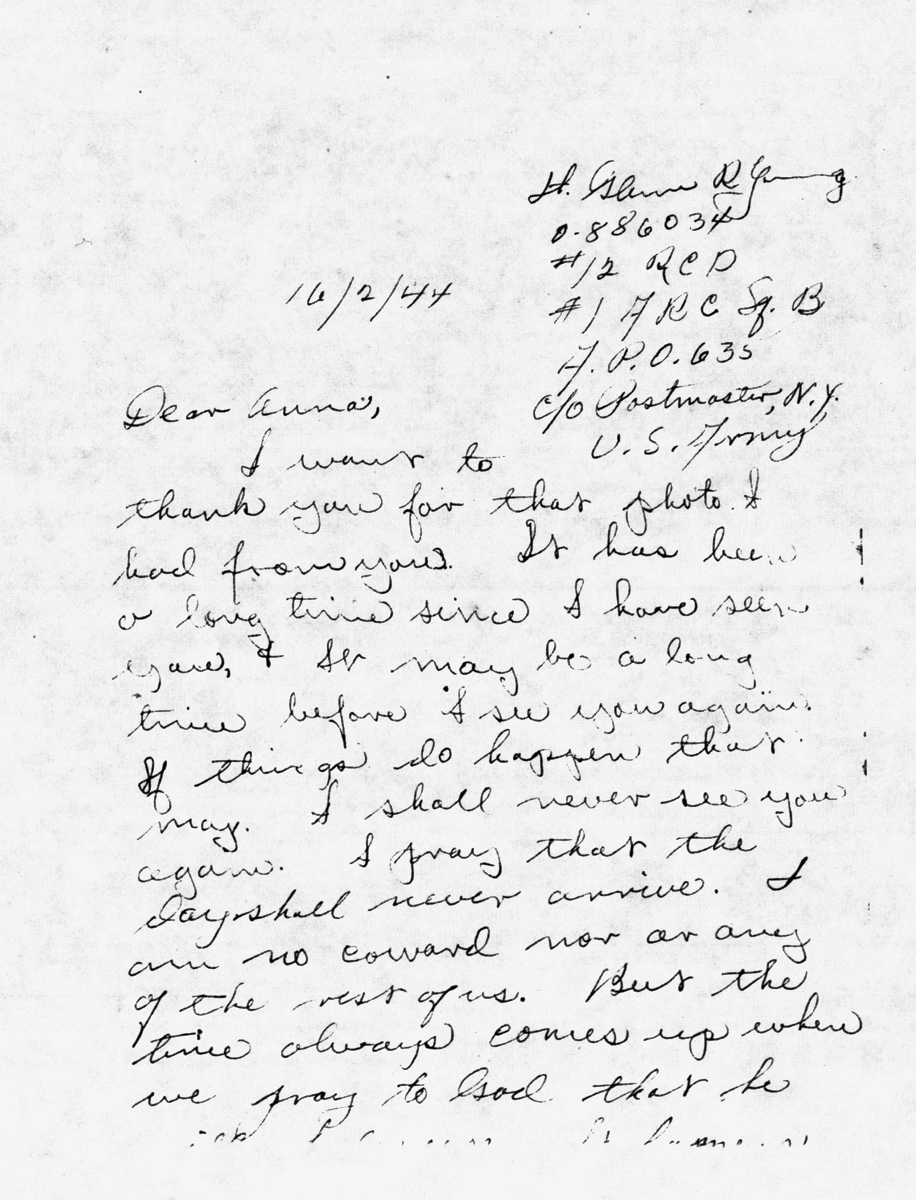

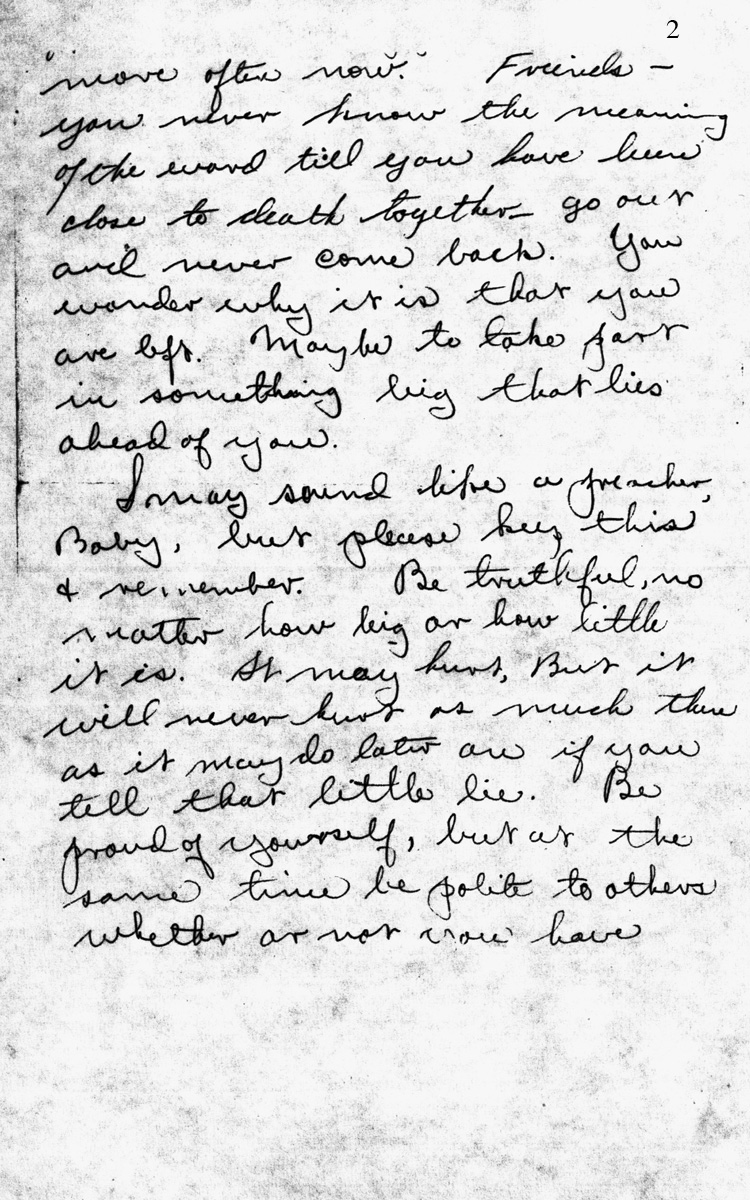

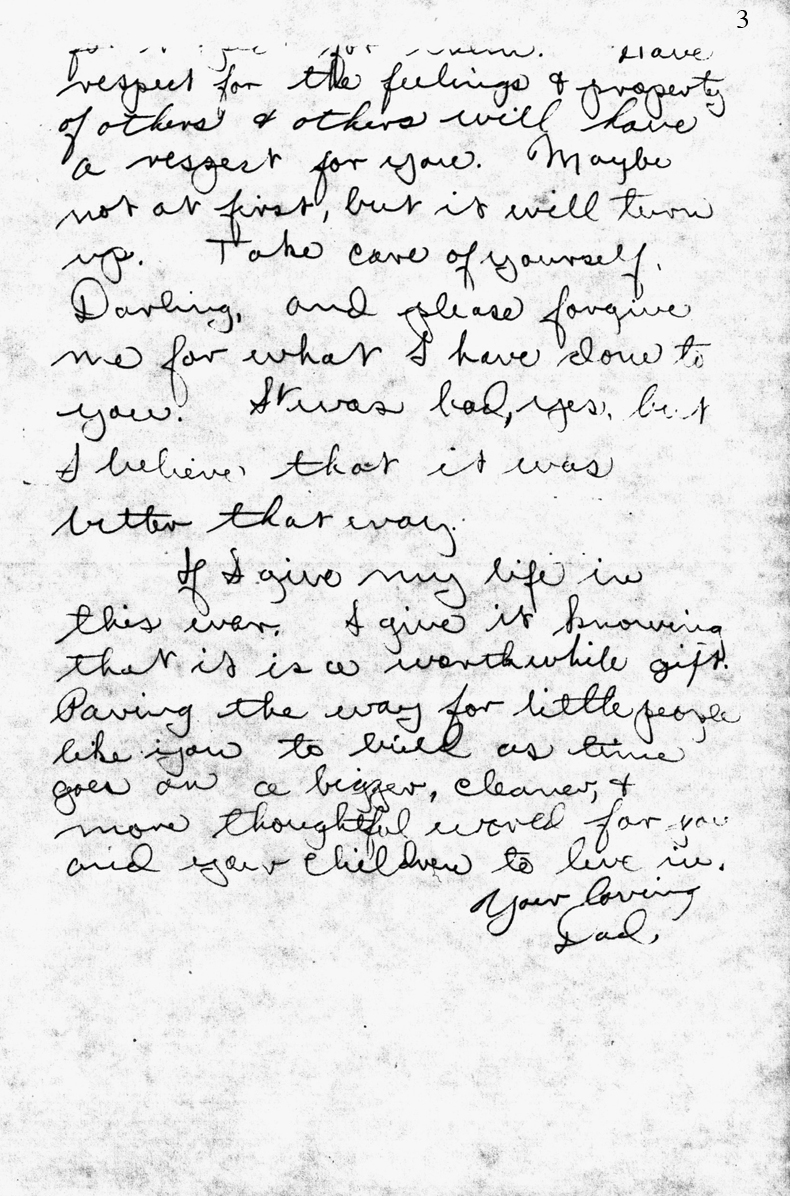

Courtesy of historian, Will Lindsay: Click any image to enlarge. Lt. Glenn R. Young, known as Bob, he enlisted in the RCAF in Oct 1941 and was given 18 months training. Assigned to active duty at the front, he was assigned to 279 Hudson Squadron at RAF Bircham Newton, England, he flew a total of 20 missions with 279 squadron. On 13 July, 1943, Glenn transferred to the United States Army Air Forces, commissioned as a First Lieutenant. He was assigned to the 496th Bombardment Squadron, of the 344th Bombardment Group, 9th Air Force, flying B-26 Marauder, medium type bombers based at Stansted, in England. On February 2, 1944 Young wrote a letter to his daughter shown below. He wanted to express himself to her in case he did not survive. He was divorced from her mother at this point.

.

On February 2, 1944 Young wrote a letter to his daughter shown below. He wanted to express himself to her in case he did not survive. He was divorced from her mother at this point.

. .

.

.

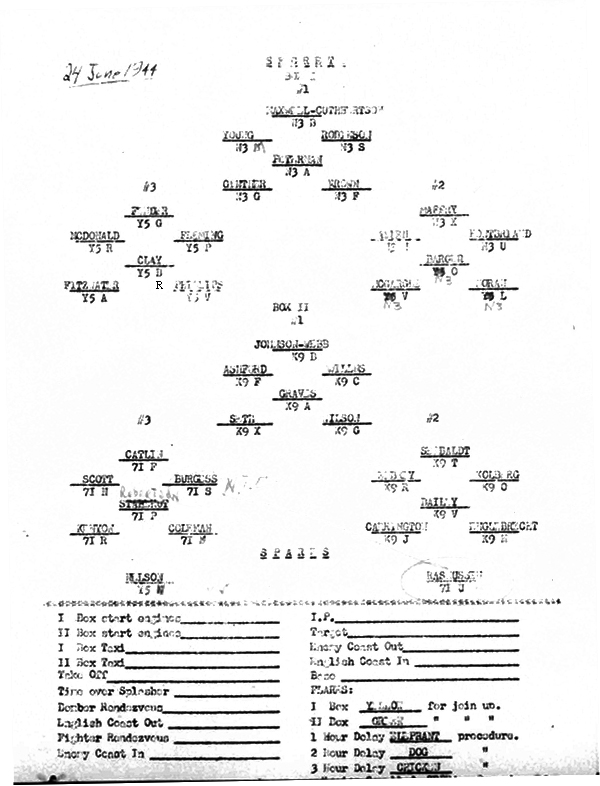

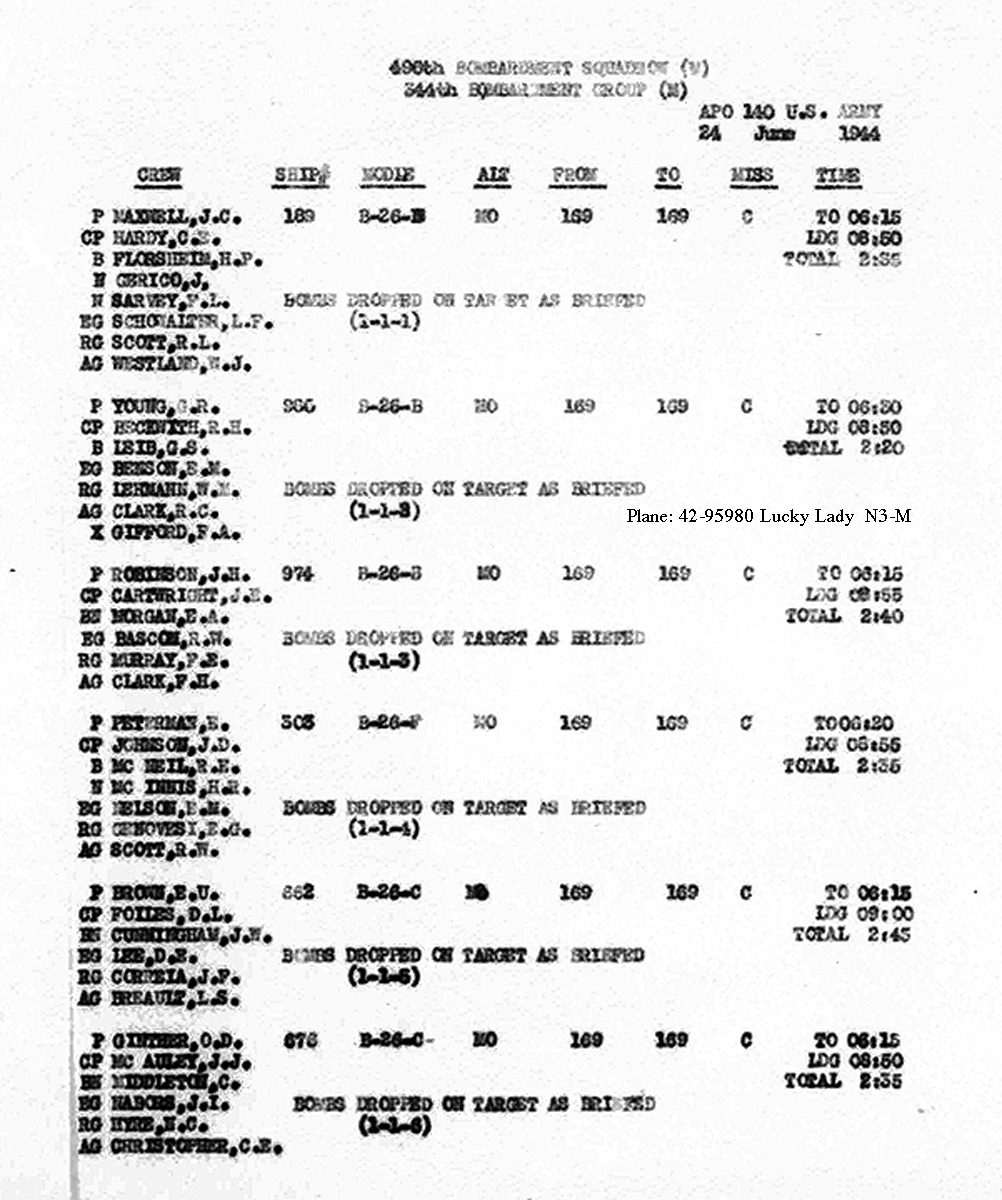

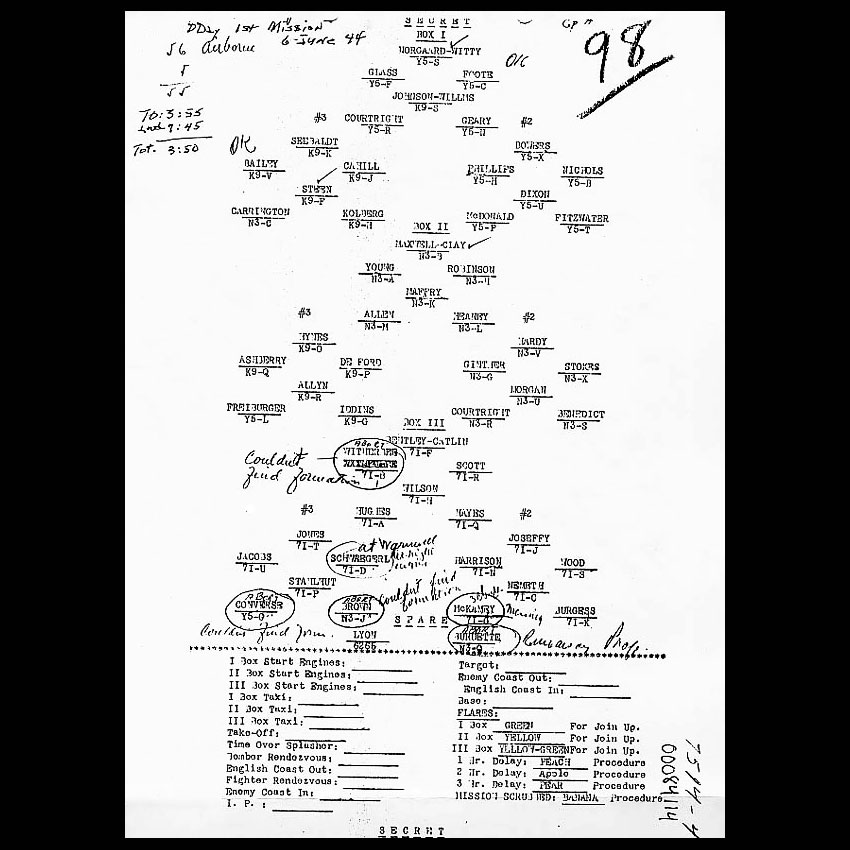

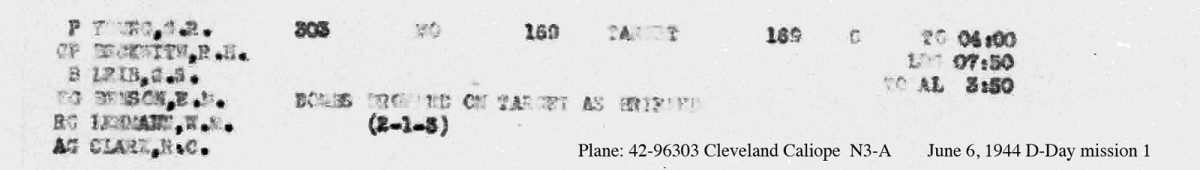

. He took part in the 496th’s mission on the morning of the D-Day invasion, flying aircraft B-26 N3*A at the front of box II.

He took part in the 496th’s mission on the morning of the D-Day invasion, flying aircraft B-26 N3*A at the front of box II.

.

.

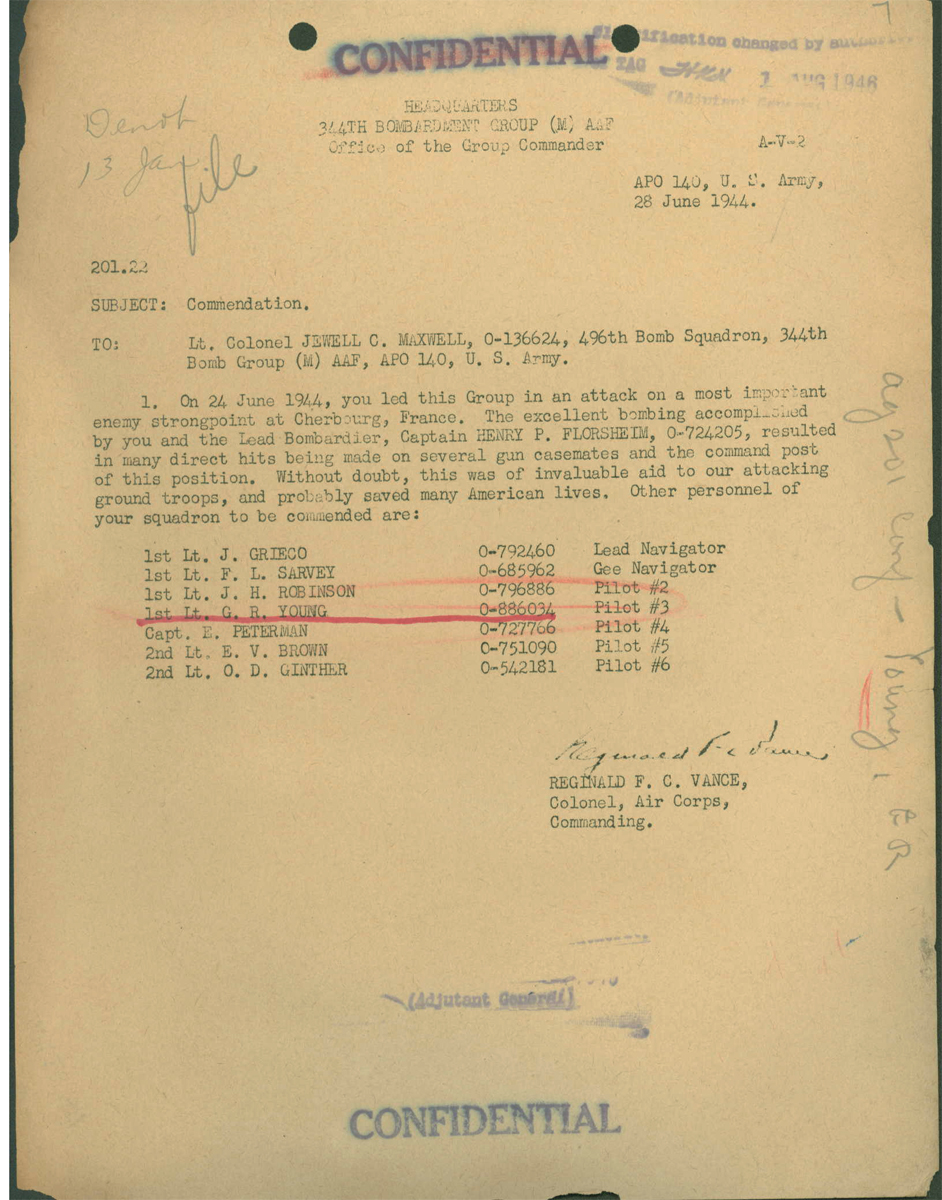

Lt. Young received a commanding officers commendation for accurate bombing in the attack on the gun emplacements at Utah Beach, and for an accurate attack on Cherbourg Port on 6/6/44.

In late October, 1944, the 496th were sent to a French Base, Cormeilles-en-Vixen, where Lt. Young was quartered in a wooden building that the Germans had constructed to house their “collaborators”. His room accommodated about 12 personnel of which a fellow 496th pilot, Lt. Jack Bornhoeft, was a resident. Lt. Bornhoeft recalled that Lt. Young, reminded him of an English gentleman, pipe in hand, or in the side of the mouth and evidently from his RAF days, he used various English terms for parts of aircraft. Historian, Lindsay is unsure what English terms he used, but Lt. Bornhoeft recalled he used British terminology for various parts of an aircraft, this was due to his time with the British when he was in the RCAF.

He was said to be headstrong or difficult by some. Frank Carrozza describes a run-in he had with a Lt. Young.

Lt. Young received a commanding officers commendation for accurate bombing in the attack on the gun emplacements at Utah Beach, and for an accurate attack on Cherbourg Port on 6/6/44.

In late October, 1944, the 496th were sent to a French Base, Cormeilles-en-Vixen, where Lt. Young was quartered in a wooden building that the Germans had constructed to house their “collaborators”. His room accommodated about 12 personnel of which a fellow 496th pilot, Lt. Jack Bornhoeft, was a resident. Lt. Bornhoeft recalled that Lt. Young, reminded him of an English gentleman, pipe in hand, or in the side of the mouth and evidently from his RAF days, he used various English terms for parts of aircraft. Historian, Lindsay is unsure what English terms he used, but Lt. Bornhoeft recalled he used British terminology for various parts of an aircraft, this was due to his time with the British when he was in the RCAF.

He was said to be headstrong or difficult by some. Frank Carrozza describes a run-in he had with a Lt. Young.

“During training in the states I crossed paths literally with a Lt. Young, a navigator/bombardier. I was leaving the mess hall with a friend or two, Young was coming the other way.”

“We were not all that formal on the base in regard to saluting officers, after all we all flew together. The other guys saluted Young and I neglected to. Young turned around and dressed me down. ‘Don’t you know you’re supposed to salute an officer!” he said. ‘Do you want to spend a few hours standing here practicing?” he continued. I figured he didn’t want to stand there practicing with me so he let me go after the tongue lashing.” “You can bet I resented his attitude.”

“A short time later, after we had all been transported to Stansted, England, Lt. Young came up to me put his arm around me and made nice…’How ya doin’ Carrozza!’

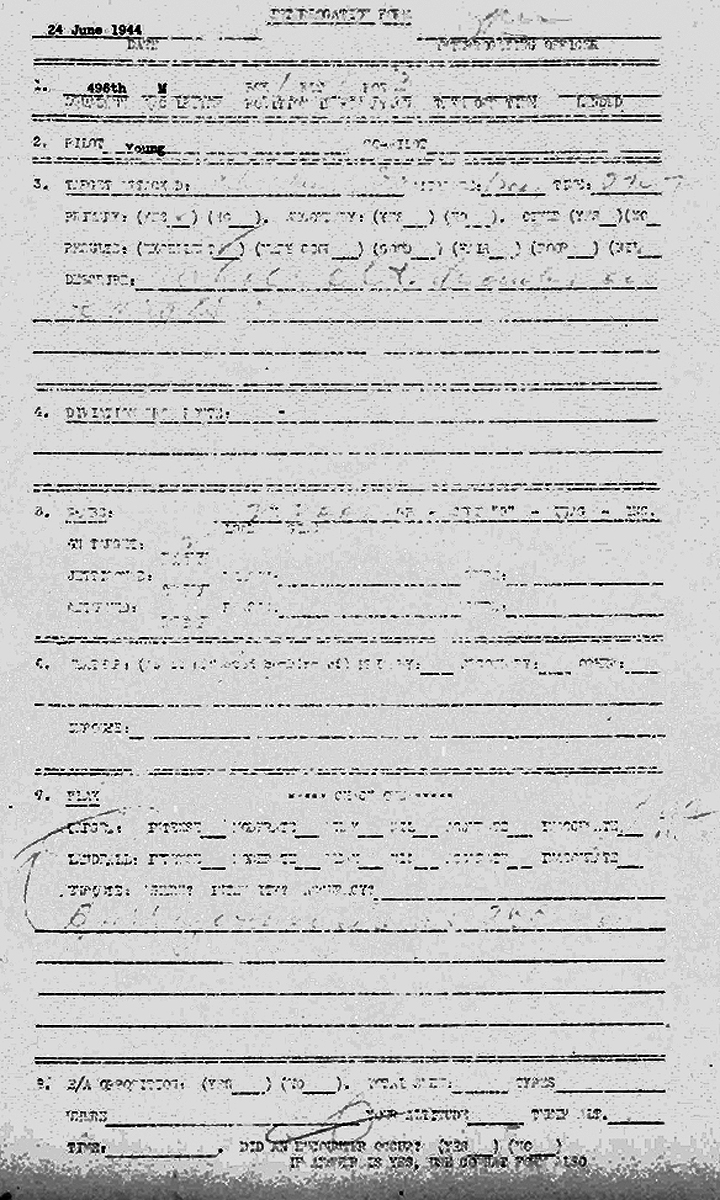

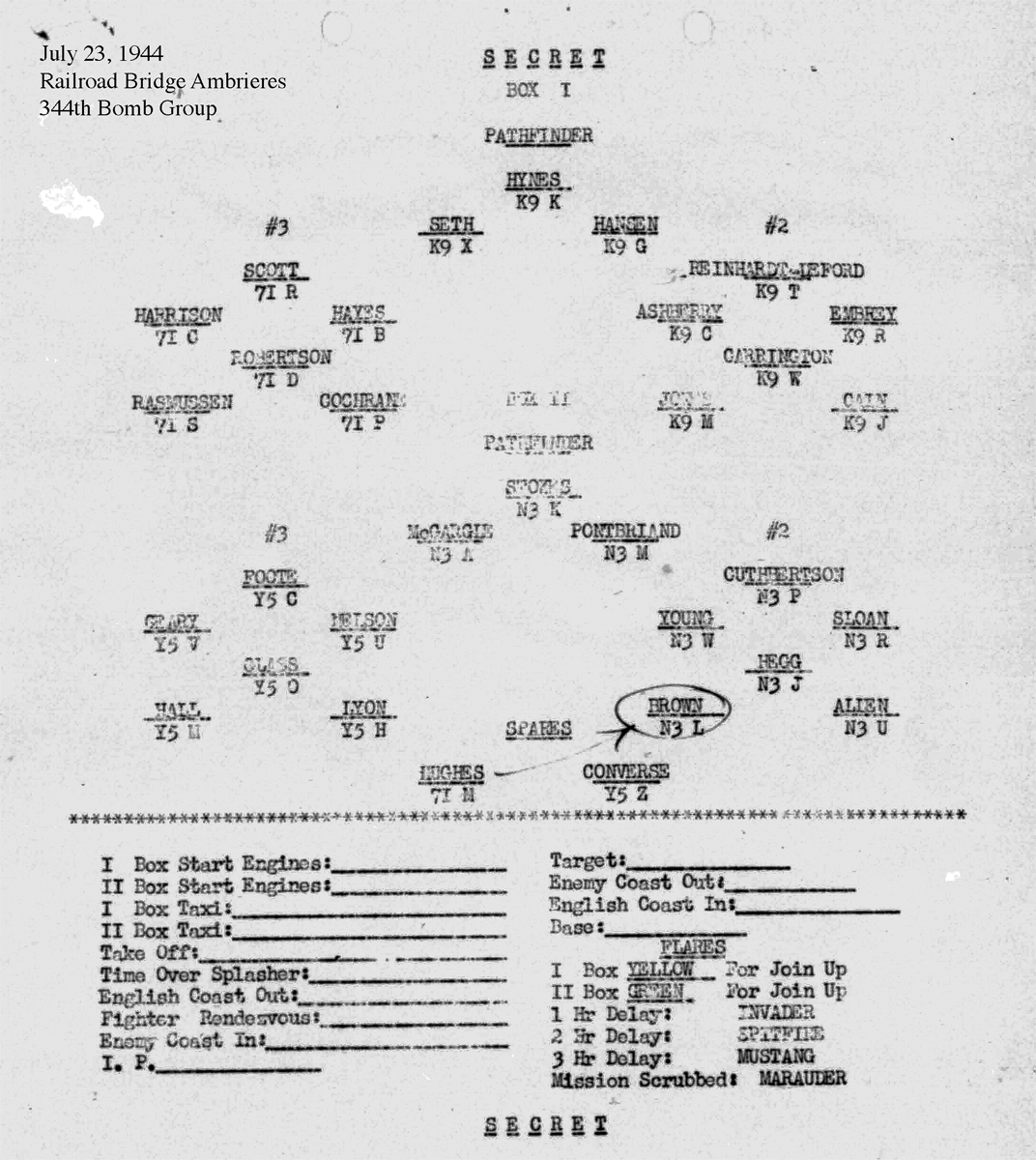

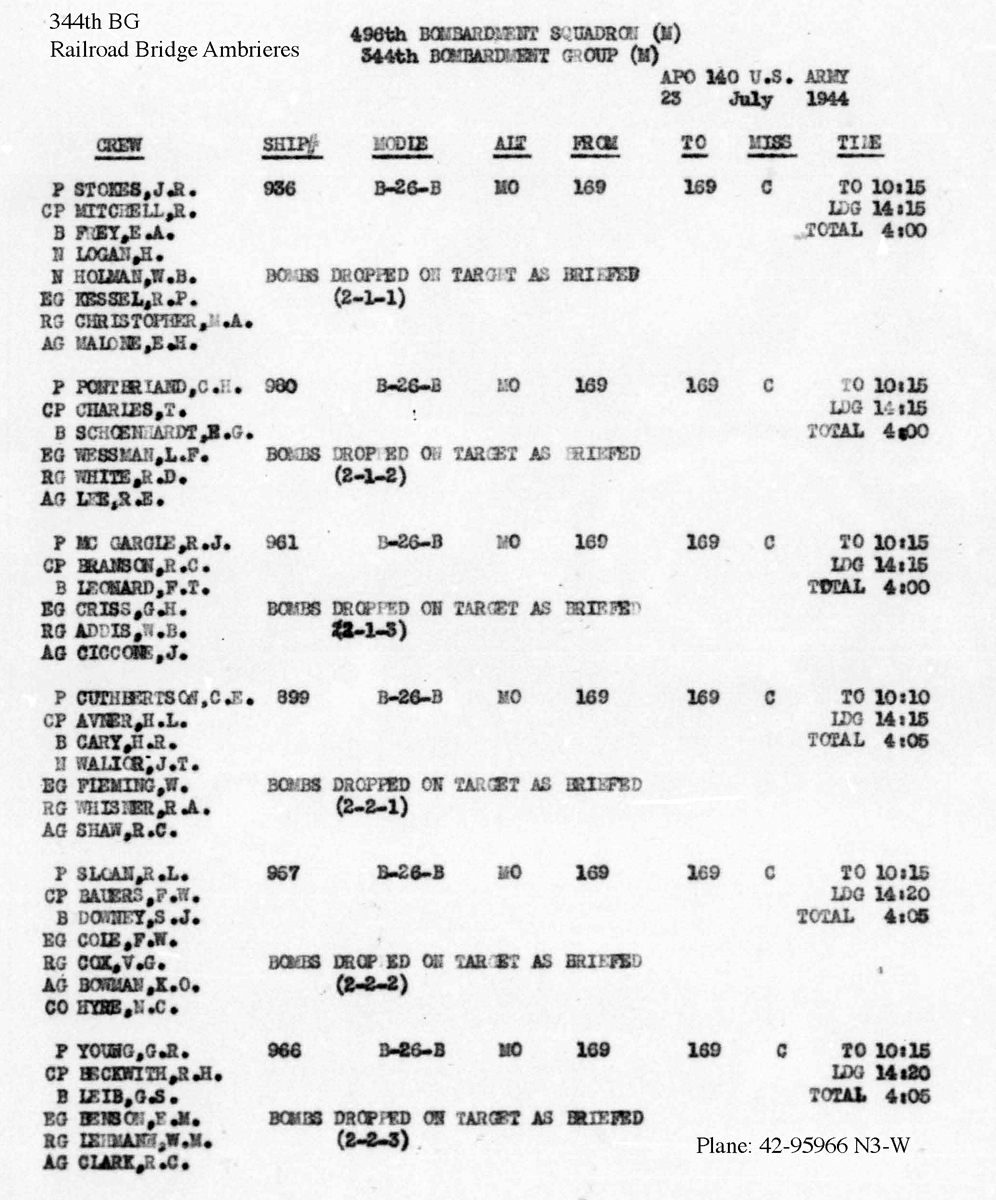

“I don’t think it was a coincidence that we had just been instructed to test our guns over the English channel during each mission. We were also told to be careful when we did it. Being a side gunner and radio operator, It could be a real liability to a Lieutenant who had made enemies.” There were two Lt. Youngs in the bomb group. It is not clear if this was Lt. Glenn Young. For a mission on June 24, 1944, Young received a commendation from commanding officer, Reginald Vance for leading an excellent bombing mission. On July 23, 1944 Young and the 344th Bomb Group flew a mission to destroy a railroad bridge in Ambrieres, France. .

.

.

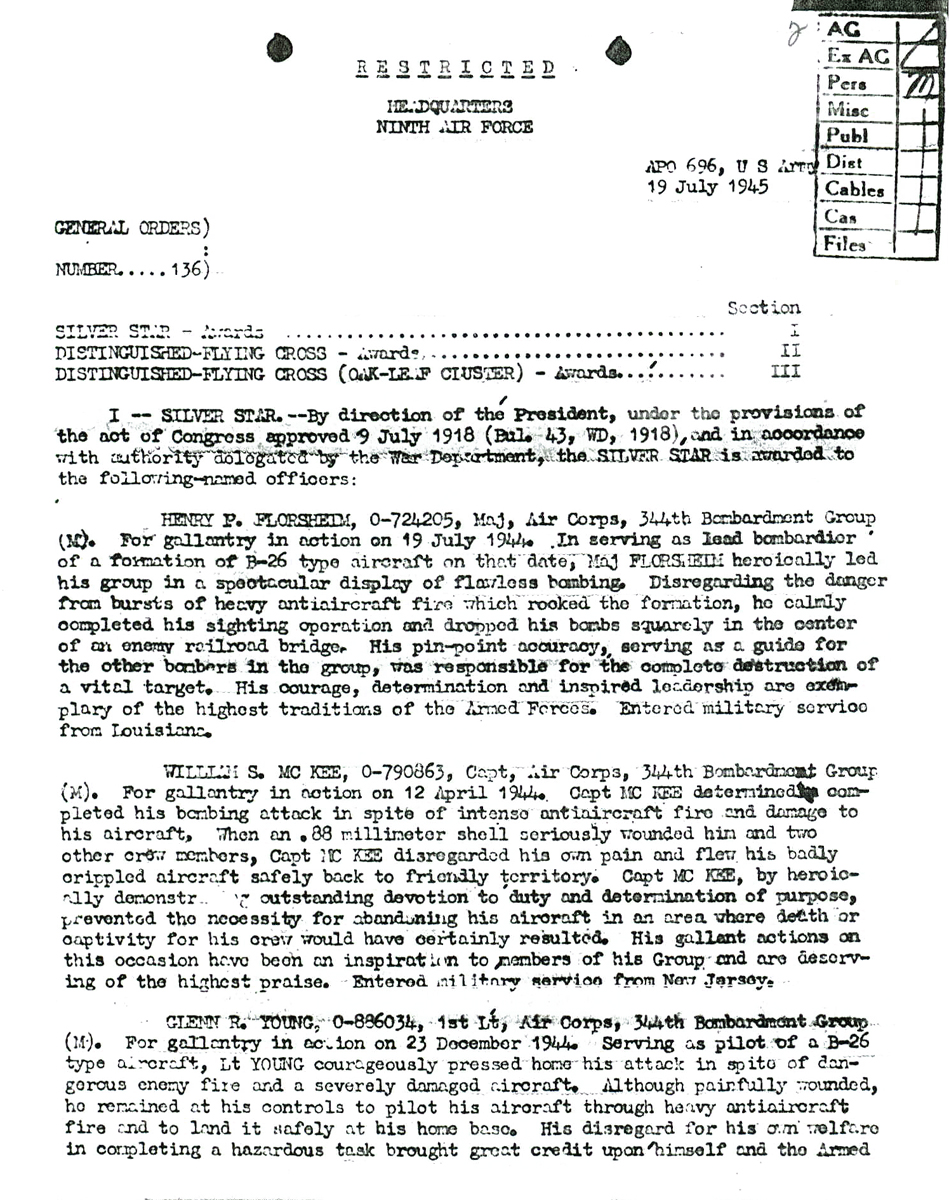

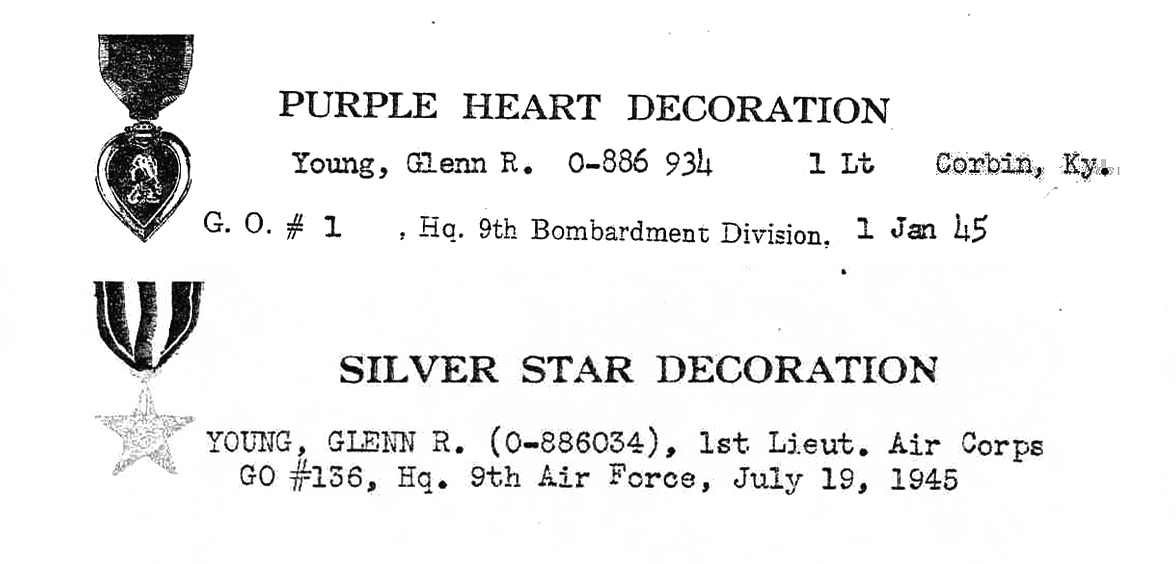

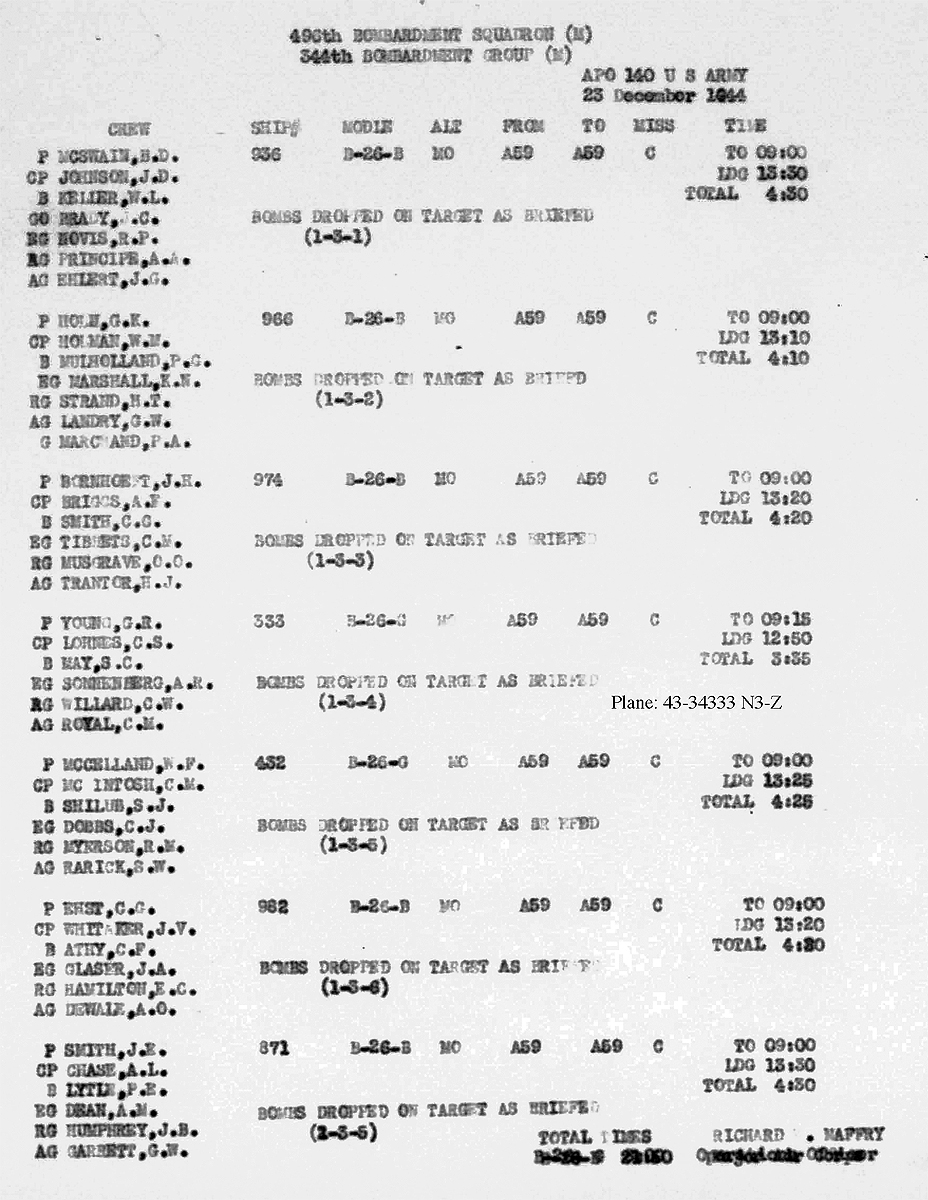

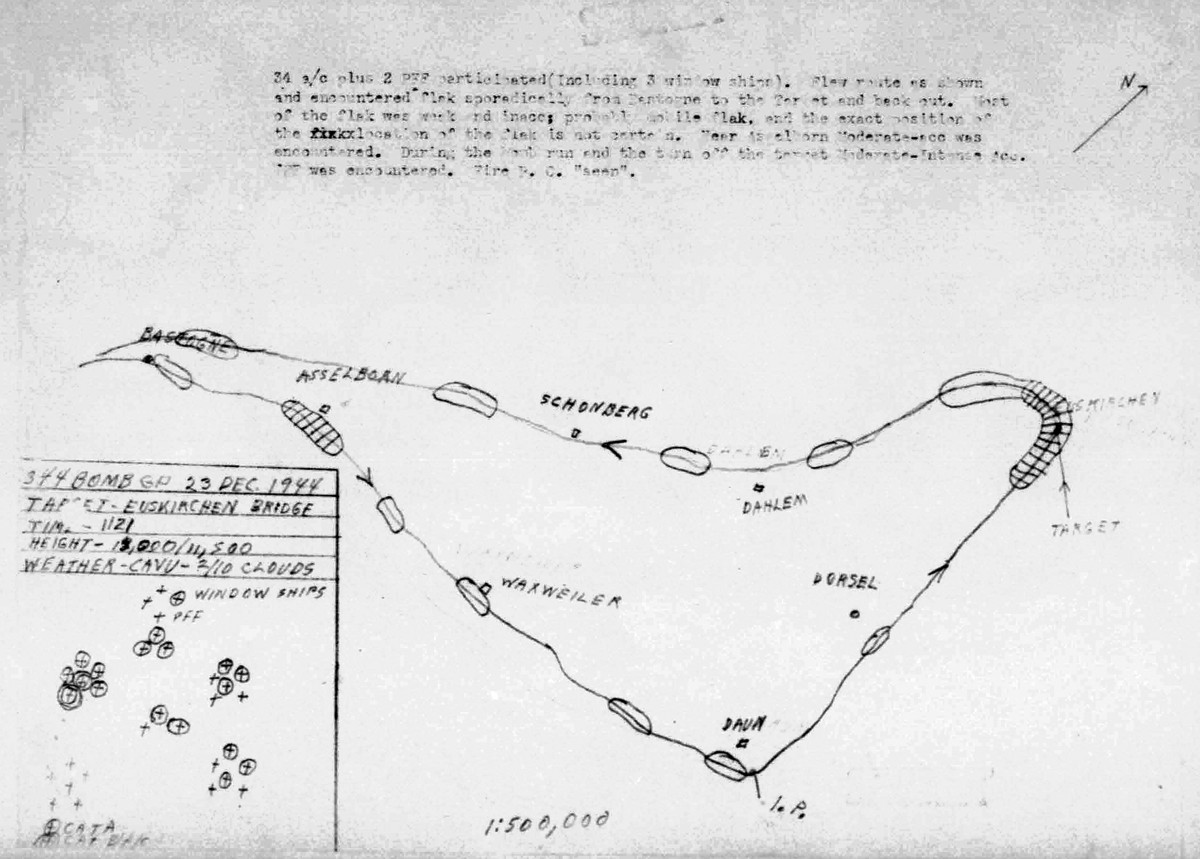

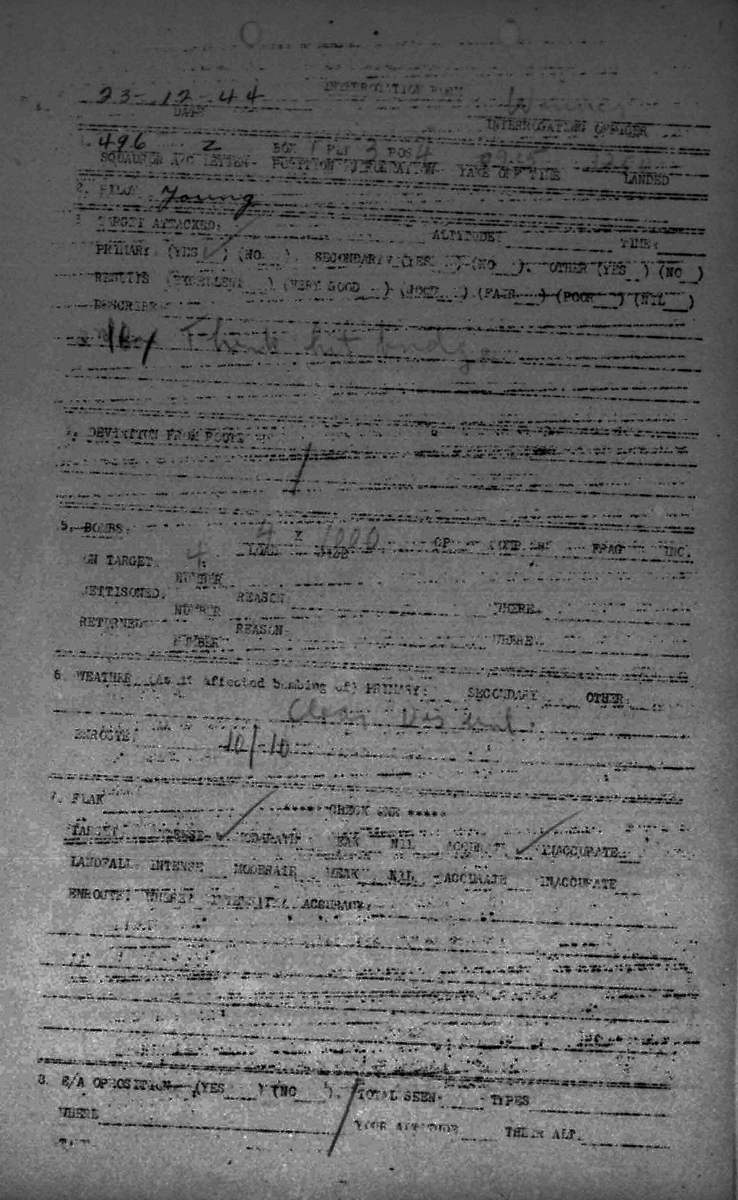

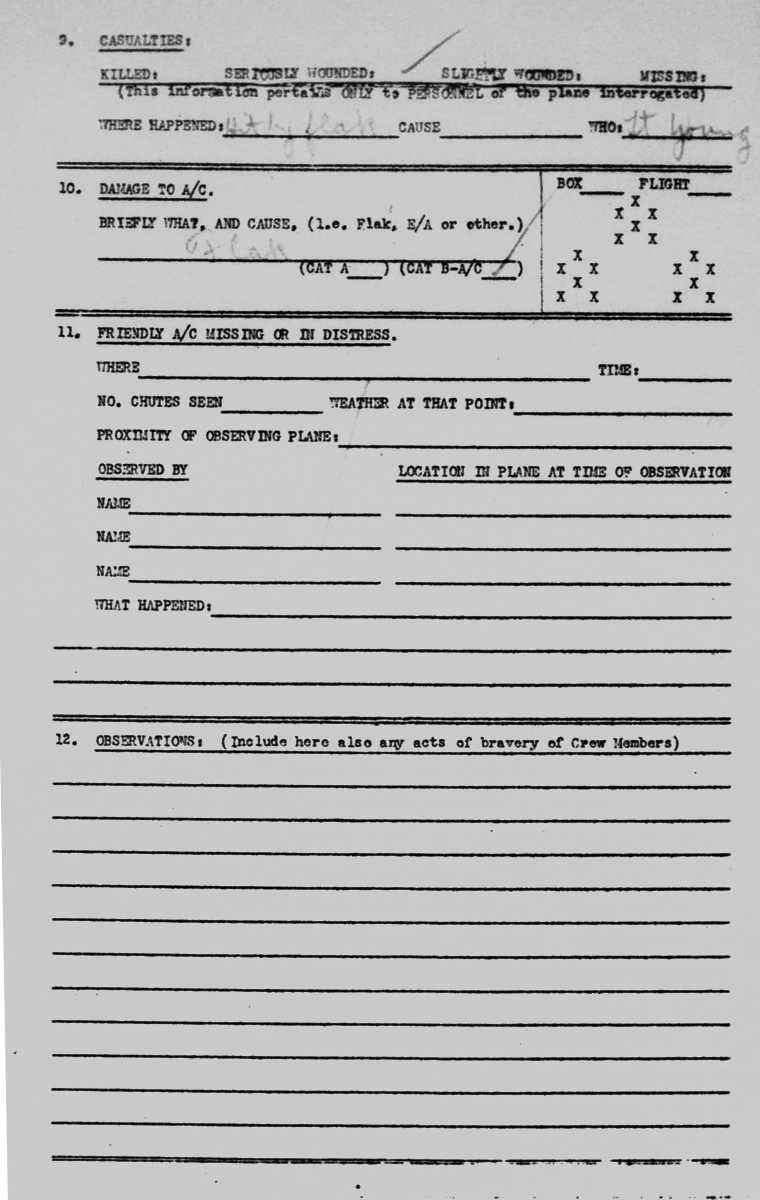

In December 1944, Lt. Young was awarded the Silver Star medal for taking out a bridge during the Battle of The Bulge in the Ardennes Forest. During this mission, he was severely injured by FLAK and suffered tremendous blood loss. He managed to nurse his damaged aircraft back to base and was commended for his exemplary bravery in performing his duties under intense enemy action.

.

.

.

.

.

Excluding his missions with the RAF, he flew 65 combat missions in the European Theater of Operations with the USAAF before arriving in Northern Ireland as a test pilot at Langford Lodge in early 1945.

.

.

In December 1944, Lt. Young was awarded the Silver Star medal for taking out a bridge during the Battle of The Bulge in the Ardennes Forest. During this mission, he was severely injured by FLAK and suffered tremendous blood loss. He managed to nurse his damaged aircraft back to base and was commended for his exemplary bravery in performing his duties under intense enemy action.

.

.

.

.

.

Excluding his missions with the RAF, he flew 65 combat missions in the European Theater of Operations with the USAAF before arriving in Northern Ireland as a test pilot at Langford Lodge in early 1945.

.

.

.

.

. Glenn preferred to be called Bob, his daughter recalled. Sadly, before he was due to depart Langford Lodge for the states, he was killed in an aircraft accident just off the airfield in June 1945.

Historian, Will Lindsay has been researching Lt. Young for over ten years now. It all started with researching aircraft accidents that were located in the vicinity of where he lives, knowing that a huge American WWII base was just down the road. He inquired to his grandmother if she remembered any accidents during the war, to which she remembered a P-38 crash on the outskirts of the village. From researching this accident, Will Lindsay managed to track down all other aircraft accidents from that base, which was the former Base Air Depot 3, Langford Lodge.

Glenn preferred to be called Bob, his daughter recalled. Sadly, before he was due to depart Langford Lodge for the states, he was killed in an aircraft accident just off the airfield in June 1945.

Historian, Will Lindsay has been researching Lt. Young for over ten years now. It all started with researching aircraft accidents that were located in the vicinity of where he lives, knowing that a huge American WWII base was just down the road. He inquired to his grandmother if she remembered any accidents during the war, to which she remembered a P-38 crash on the outskirts of the village. From researching this accident, Will Lindsay managed to track down all other aircraft accidents from that base, which was the former Base Air Depot 3, Langford Lodge.

When the aircraft arrived at Langford Lodge, they were assessed and either majorly overhauled or scrapped for salvageable parts, the vast majority of these aircraft were A-20’s, but also B-24’s, B-17’s. It was while undertaking a test flight in one of these War-Weary A-20 aircraft that he was killed, sadly along with another young Lieutenant who came up for a ride to see what the A-20 was all about. He was only at the base for the day to replace a pilot who had suddenly taken ill, he was to replace this pilot and ferry a C-47 and it’s crew back to Metz in France. A few days after the accident, Lt. Young should have been making his way home to the states with his English wife and recently born son. ”

“The official report blamed Lt. Young for allowing his aircraft to stall while in a steep climbing turn. What the investigators of the time did not take into account, was that the engine, into which he was turning, had quit, which brought on the onset of the stall and subsequently developed into an inverted spin into the wing. This was only discovered ten years ago when I excavated the remains of his aircraft.” I found an intact propeller blade, which indicates that it was not moving when it came into contact with the ground. This implies that engine failure was the main cause of the series of events that took place which ended in a fatal crash.”

When the aircraft arrived at Langford Lodge, they were assessed and either majorly overhauled or scrapped for salvageable parts, the vast majority of these aircraft were A-20’s, but also B-24’s, B-17’s. It was while undertaking a test flight in one of these War-Weary A-20 aircraft that he was killed, sadly along with another young Lieutenant who came up for a ride to see what the A-20 was all about. He was only at the base for the day to replace a pilot who had suddenly taken ill, he was to replace this pilot and ferry a C-47 and it’s crew back to Metz in France. A few days after the accident, Lt. Young should have been making his way home to the states with his English wife and recently born son. ”

“The official report blamed Lt. Young for allowing his aircraft to stall while in a steep climbing turn. What the investigators of the time did not take into account, was that the engine, into which he was turning, had quit, which brought on the onset of the stall and subsequently developed into an inverted spin into the wing. This was only discovered ten years ago when I excavated the remains of his aircraft.” I found an intact propeller blade, which indicates that it was not moving when it came into contact with the ground. This implies that engine failure was the main cause of the series of events that took place which ended in a fatal crash.”